The fascinating story about witnessing the 2023 total eclipse at sea, off the coast of Australia.

As the Co-Director of Swinburne’s Space Technology and Industry Institute, I can apply my background in astrophysics to help translate Swinburne’s cutting-edge research into ways to help grow Australia’s space industry, including finding amazing opportunities for our students. However, I will always have a passion for communicating our Universe’s wonders and witnessing them firsthand.

The map showing the trail of the total solar eclipse off the coast of Australia. Image credit: Swinburne University of Technology

So when I was invited to be the Astronomical Society of Australia’s ambassador for P&O’s Ningaloo Eclipse Cruise, giving me the chance to see my first total solar eclipse and help produce a professional astronomy outreach program, I said yes immediately.

I teamed up with Jackie Bondell, Education and Public Outreach Coordinator for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Discovery (OzGrav) and the ASA’s Education and Public Outreach Committee chair. We worked to create a portfolio of diverse researchers and presenters and were honoured when Krystal DeNapoli agreed to join us to talk about Indigenous Astronomy.

I don’t think the cruise line had ever had a 12 inch Dobsonian Telescope brought on board or considered how hard it would be to photograph an eclipse on a moving ship. Our cruise departed Monday 17 April, but the eclipse was not going to happen until around midday on 20 April so there was plenty of time for us to fill.

Co-Director of Swinburne’s Space Technology and Industry Institute, Dr Rebecca Allen, travelled on board P&O Cruises’ specialist ‘Ningaloo King of Eclipses’ cruise to witness the 2023 total eclipse off the coast of Western Australia. Image credit: Swinburne University of Technology

Krystal and I were scheduled to speak the first day, so we didn’t have much time to get our sea legs before jumping on stage. Krystal’s talk was incredibly well received with copies of her book, Sky Country, selling out in minutes.

I talked about the James Webb Space Telescope and the amazing science that our researchers, including Professor Karl Glazebrook, Dr Themiya Nanayakkara and Associate Professor Ivo Labbe, are undertaking. I also spoke about how Australians are using similar technology and techniques to study Earth and rapidly detect dangerous events such as bushfires.

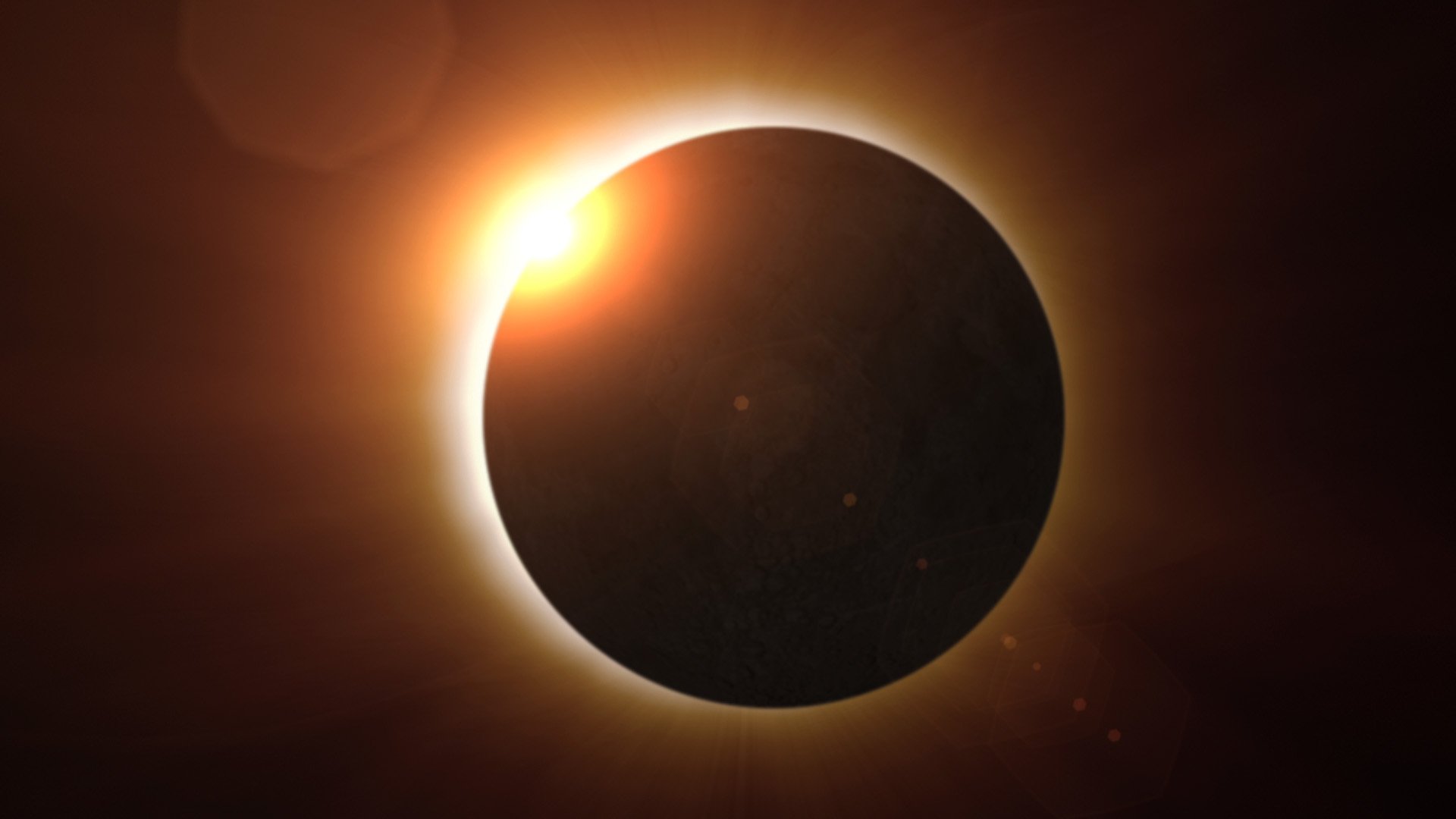

Total solar eclipses are special for a few reasons. Our Moon is just the right size and distance that it occasionally eclipses the Sun during a new Moon (the phase of the Moon where the Moon appears completely in shadow because the Sun is behind it from Earth’s point of view).

But we don’t get a total eclipse every new Moon because the Earth-Moon distance changes, and the Moon isn’t always in the correct plane of its orbit to totally block the Sun’s light. When this alignment comes together we get an eclipse… but they only last seconds to minutes.

As Earth is mostly water, the path of totality rarely crosses a highly populated location. It can be decades to centuries before crossing the same place again.

Observing an eclipse by ship is advantageous because you can move to the best location to capture the longest period of totality (when the Sun is completely covered by the Moon and is safe to look at). If you look at the map below you can guess where we tried to be. To have stability for photographers we opted for a location a bit closer to land, but within the 60 second zone.

The days flew by, with our talks and presentations receiving fantastic feedback. On Thursday morning the ship was bustling early on with guests staking out ideal places to view and capture the eclipse.

Matt Dodds, an educator, outreach program coordinator, and astrophotographer (@stargazingadventures) and his mentee, Lachlan Wilson (@astrolach), a seventeen-year-old award winning astrophotographer, were positioned in the middle of the deck between the swimming pools where they could capture the entire event.

We headed to the back of the ship to a special area, where we made pin hole cameras with Jatz crackers (I had to keep my 18-month-old from eating them) and waited patiently as the sky slowly darkened. Over the course of about 90 minutes, we checked the eclipse’s progress with special viewers and even adapted a few to take pictures with our smartphones.

At 11:20 we were informed over the PA system that the main event was almost here. The ship got dramatically quiet as the final minutes ticked by and we tried to be still so as not to disturb the photographers.

And then it happened, the Moon slipped in front of the Sun and for almost 60 seconds we sat in eery darkness as the Sun’s corona was on full display. And then it was over.

This illustration depicts a rare alignment of the Sun and Moon casting a shadow on Earth. Image credit: NASA

I instantly understood the addiction of eclipse chasers seeking to experience this unique cosmic event. We watched as the Moon continued to make her way and reveal the Sun’s disk again. It was a perfect eclipse with not a cloud in the sky and we knew we had seen something special.

I can’t wait until 2028 when the next solar eclipse will cross Australia from the tip of WA to Sydney with almost five minutes of totality.

Source: Swinburne University of Technology