Frontera and Stampede2 supercomputers help scientists resolve and analyze challenging plasma shock wave structures.

Imagine the explosive disturbance caused by a jet going supersonic. A similar shock wave occurs when subatomic particles known as “solar wind” flow from the sun and strike the Earth’s magnetic field.

Now, scientists have used a recently developed technique to improve predictions of the timing and intensity of the solar wind’s strikes, which sometimes disrupt telecommunications satellites and damage electrical grids.

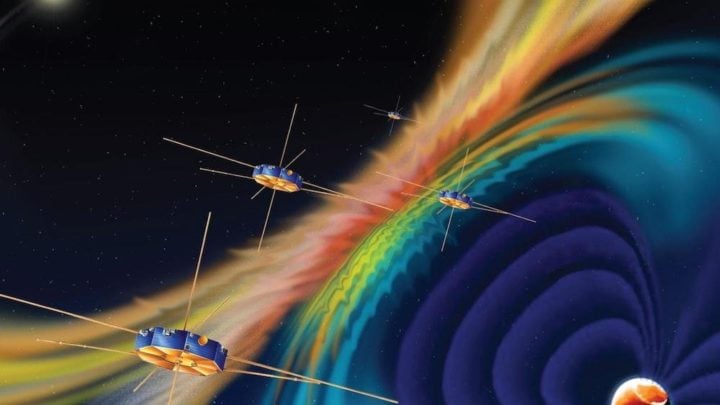

An artist’s rendering of the four satellites in NASA’s Magnetospheric Multiscale mission flying through Earth’s magnetic field. Image credit: NASA.

The research team — led by James Juno, a staff physicist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) — used what is known as “field-particle correlation” (FPC) for a detailed view of how shock waves composed of plasma, the hot, charged state of matter that makes up 99% of the visible universe, can heat up blobs of plasma in outer space.

FPC is an algorithm that digests data produced by spacecraft or computers and determines how the energy of magnetic fields and moving plasma particles change back and forth. The process gives precise information about the particles’ positions and velocities as the changes occur.

“Though much of what we found was already well known, heat transfer has never been examined in this way before,” said James Juno, a staff physicist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) and lead author of a paper reporting the results in The Astrophysical Journal.

“The fact that this technique works as well as it does shows us that there are new ways to look at old problems.”

PPPL scientists study plasma because it fuels fusion reactions within doughnut-shaped devices known as tokamaks and twisty facilities known as stellarators. Plasma is a soup of atomic nuclei, or ions, electrons, and neutral atoms that together allow the flow of electric current.

That flow allows plasma to respond to magnetic fields, which scientists use to corral the plasma within fusion facilities. Researchers are trying to harness fusion, which drives the sun and stars, to generate electricity without producing greenhouse gases and long-lived radioactive waste.

The FPC technique reveals plasma behavior never observed before, including which parts of the plasma are heating up and which physical processes are responsible. Older techniques can produce only broad pictures of where and how a plasma heats up.

“One of our key findings is that different regions of the plasma could respond to a shock wave in different ways,” Juno said. “We now have a more holistic picture of what’s going on in the shock wave interactions.”

The NSF-funded Frontera (left) and Stampede2 (right) supercomputers helped scientists model plasma shock waves. Image credit: TACC

“This means that we can discover the energy of a specific particle at a particular position and that a shock wave is transferring energy to a particular plasma region,” Juno said. “Previous methods cannot distinguish between the large variety of processes that are occurring.”

Juno and colleagues performed the FPC technique, which was developed by Gregory Howes at the University of Iowa, on data produced by a plasma simulation program known as Gkeyll (pronounced like Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. “Jekyll”).

PPPL developed the code to simulate the orbiting of plasma particles around magnetic field lines at the edge of the plasma in tokamak fusion facilities. Scientists are constantly updating the program to extend its capabilities.

The complex structures which form in phase space presented the biggest computational challenges in the study, which required significant resolution to capture and thus necessitating the use of high performance computing.

The MMS mission launched March 12, 2015. Credits: Ben Smegelsky/NASA

Study co-author Jason TenBarge was awarded a Leadership Resource Allocation on the NSF-funded Frontera supercomputer at TACC, which was used in the study. TenBarge is an Associate Research Scholar at Princeton University in the Department of Astrophysical Sciences and at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory.

“It is the more accurate resolution of these structures that allowed us to utilize novel analysis techniques such as the field-particle correlation. Studies like this have even paved the way for recent observational work utilizing data from NASA’s Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission, because these high-resolution studies have given us the necessary insights to understand the structures in phase space we measure via spacecraft,” TenBarge said.

What’s more, study co-author Gregory G. Howes of the University of Iowa was awarded an allocation also used in the study on TACC’s Stampede2 supercomputer by the NSF’s Advanced Cyberinfrastructure Coordination Ecosystem: Services & Support (ACCESS) program (formerly XSEDE).

The approach the Gkeyll code takes to modeling the plasmas of interest to the scientists is more computationally expensive, but it eliminates sources of error in more traditional approaches.

TenBarge added, “These simulations would not have been possible without the resources of Frontera and Stampede2. We have been utilizing both resources for years now, with both systems also proving vital in the first study.”

“Modeling plasmas is a significant computational challenge. To understand fundamental processes such as how a star produces its magnetic field or whether a hot fusion plasma will be confined requires resolving vast temporal and spatial scales, down to the details of the protons and electrons motions about magnetic fields. A complex, dizzying array of instabilities and waves govern plasma dynamics. Without high performance computing resources, it would be hopeless to understand the interplay of all these processes and their impact on the evolution of the plasma, which impacts everything from our understanding of the universe to technological breakthroughs here on Earth,” TenBarge said.

“Gkeyll has many components that apply to a range of plasma problems, from space plasmas to laboratory fusion experiments,” said Ammar Hakim, PPPL deputy associate laboratory director for the computational sciences department.

“And with new National Science Foundation investment in the Cyberinfrastructure for Sustained Science Innovation program, we are improving Gkeyll to make it a national resource for plasma simulations.”

Scientists can use FPC to glean information from current space voyages like NASA’s Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) mission, which employs four satellites flying in formation in the region of space affected by Earth’s magnetic field.

“The MMS mission presents an incredible opportunity to study space plasmas using the FPC technique,” says Collin Brown, researcher at the University of Iowa and co-author of the paper. “That significantly enhances our ability to study the three-dimensional structure of energy transfer.”

Moreover, “it’s one thing to use a supercomputer to reproduce a plasma shock wave,” Juno said. “But the FPC technique can actually help you learn new things about the world. And that’s exciting.”

Source: TACC