An amateur archaeologist exploring a dried-out, ancient stream channel called Blackwater Draw near Clovis, New Mexico, made a startling discovery in 1929. He came across chiseled stone points strewn among mammoth fossils. Razor-sharp edges bordering each artifact gracefully curved up to a pointed tip. Thin grooves chipped into the bases of these stone points suggested that they were spearpoints that people had once attached to handles or poles.

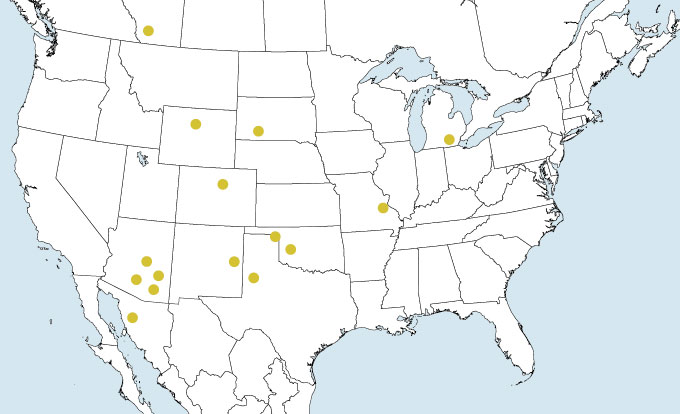

Researchers who examined the Blackwater Draw finds saw them as clear evidence of mammoths having been killed by human hunters sometime in the past. Ensuing generations of archaeologists filled out the picture of an intrepid mammoth-killing bunch, dubbed the Clovis people, who spread across North America between around 13,500 and 12,500 years ago. Clovis points or skeletal damage presumably caused by them have been found among mammoth bones at 11 North American sites, including Blackwater Draw. Two other North American sites containing mastodon bones, one featuring remains of extinct elephant-like creatures called gomphotheres, plus a site that yielded camel and horse fossils also include Clovis points or evidence of injuries from sharp, pointed stones (SN: 8/9/14, p. 7).

Archaeologists typically refer to these places as kill sites. It’s long been assumed that Clovis hunters must have left spearpoints lying among the bones of mammoths and other massive creatures after killing and butchering them. If so, Clovis big-game hunters possibly contributed to the extinction of their enormous prey (SN: 11/24/18, p. 22).

But the Clovis people’s status as adept killers of tusked beasts weighing up to about 9 metric tons has come under fire. New experimental and archaeological studies suggest an entirely different scenario, says archaeologist Metin Eren of Kent State University in Ohio. Clovis points had many uses, like a Swiss Army knife, Eren contends. Spear-throwing hunters might have occasionally killed a mammoth, especially one separated from its group or slowed due to injury. More often, these tools served as knives to cut meat off carcasses of already dead mammoths or as dart tips hurled to scare away other scavenging animals drawn to mammoth remains, Eren and his colleagues conclude in the October Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Big protection

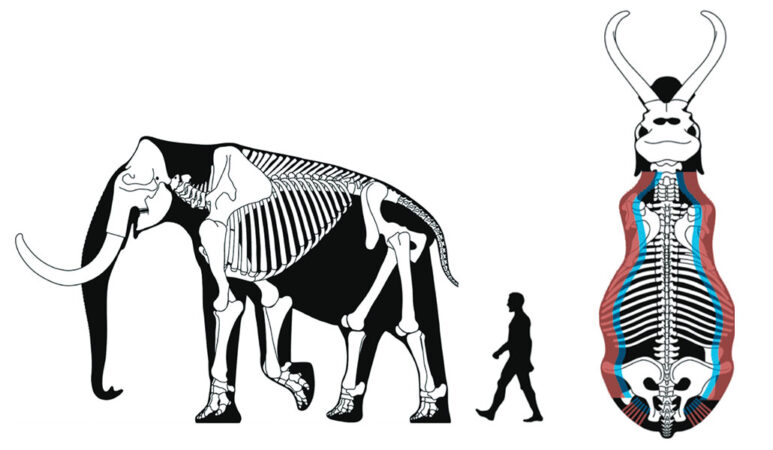

A mammoth’s skeleton shows ribs and other bones that sheltered internal organs. A view from the top, right, shows presumed average (red) and maximum (blue) penetration depths of Clovis points hurled at high speeds at a mammoth, based on experimental evidence, assuming the weapons passed through dense hair and a thick hide, and avoided bones.

M.I. Eren et al/J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2021

M.I. Eren et al/J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2021

“It’s not clear that Clovis points attached to spears could even have penetrated a mammoth’s hide,” Eren says. “We need to stop assuming that Clovis people and earlier Stone Age groups [in Asia and Europe] must have been mammoth hunters.”

His argument has been greeted with interested skepticism by some Clovis investigators. “We have an instrument, the Clovis point, that keeps showing up in direct association with dead [mammoth] bodies,” says archaeologist David Kilby of Texas State University in San Marcos. “I remain convinced that Clovis points were designed to serve as reliable hunting weapons.”

Mammoth challenges

Eren made the same argument not too long ago. A spear tipped with a Clovis point and hurled from a spear thrower “could have easily taken down the largest Stone Age beasts,” he said on camera in an episode of the 2015 PBS documentary series First Peoples.

Since then, several lines of evidence have led Eren to retract that claim. Crucial clues came from reconstructions of mammoths’ skeletal and internal anatomy — both from earlier studies by other researchers, as well as new evidence gathered by Eren’s group. The reconstructions show how well-protected these creatures were from spears heaved or thrust at them.

Eren’s team combined measurements from Asian woolly mammoths and Columbian mammoths of North America, the presumed prey of Clovis people. Several frozen carcasses recovered in Asia indicate that woolly mammoth skin was 2 to 3 centimeters thick on average, the group estimates. Beneath the skin lay 8 to 9 centimeters of fat. And above that skin, woolly mammoth hides were covered by 5 to 15 centimeters of dense underfur topped by a layer of outer hairs 10 to 60 centimeters long.

Using measurements of ribs from two Columbian mammoths, whose remains are mounted at a Texas museum, Eren’s team then estimated how far a Clovis spearpoint had to travel to reach vulnerable internal organs.

A Clovis point had to plunge 17 to 30 centimeters deep to kill an Asian woolly mammoth, the team calculated. The distance would be close, but not quite as deep, for Columbian mammoths, which may have lacked underfur.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Even after slicing through hair, hide, fat and tissue on the way into a mammoth’s chest, a Clovis point had to dodge a picket fence of thick ribs to reach the beast’s internal organs. A spearpoint that entered through the stomach and into an opening at the back of the rib cage would have had to travel farther than one aimed at the chest, although it’s unclear how much farther.

With those estimates in mind — and inspired by earlier experiments in which researchers thrust or hurled spears tipped with Clovis points into dead elephants — Eren put the points to the test.

In those earlier elephant experiments, spearpoints often pierced the animals’ hides. But for a variety of reasons that likely included the condition of carcasses and the speeds at which spears were launched, only some points penetrated deep enough to have reached the vital organs of a mammoth or mastodon. Eren used a lab setup that offered a better chance of shooting Clovis points deep into a hunting target than would have been possible in an actual encounter with a mammoth-sized creature. Yet even with this advantage, Eren’s results suggest that Clovis points generally did not penetrate deep enough to have been effective mammoth killers.

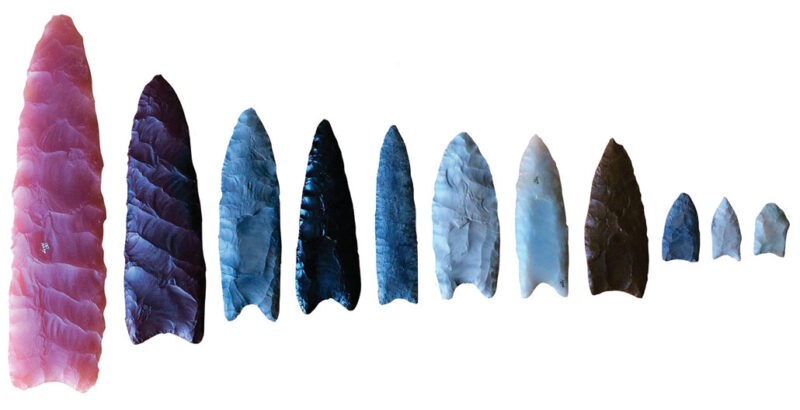

In one study published in the July 2020 Lithic Technology, replicas of seven types of Clovis points covering the sizes and shapes that have been found at archaeological sites were fastened to wooden shafts. The sizes ranged from a bullet-shaped point about two-thirds as long as an adult’s thumb to a missile-shaped point nearly as long as a pencil. A bow mounted on a shooting device fired each type of Clovis point 30 times into blocks of moist clay from a distance of about 1.8 meters. Spears traveled at a speed in the upper range of shots that have been propelled by people using spear-throwing tools. The clay blocks, fortified with crystalline silica dust, provided slightly less resistance than the tissue of an elephant or other large animal.

Clovis points found at sites across North America come in a range of sizes and shapes (several shown above).M.I. Eren et al/Lithic Technology 2020

Clovis points found at sites across North America come in a range of sizes and shapes (several shown above).M.I. Eren et al/Lithic Technology 2020

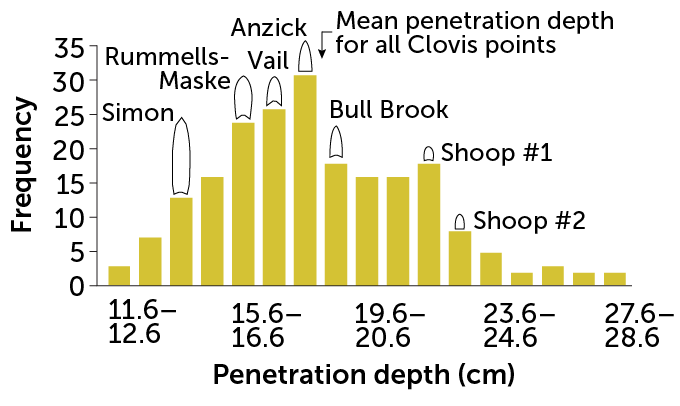

Over 210 shots, Clovis points penetrated clay blocks — which lacked the thick skins of mammoths that would have slowed or blocked spears thrown during actual hunts — to an average depth of 18.6 centimeters, Eren says. Penetration depths of four types of points equaled or fell short of the overall average. Only a couple of shots using the most successful point penetrated as deep as 28.6 centimeters. Smaller points tended to pierce deeper into targets than larger points. But the relatively broad, thick tips on all the Clovis points limited their ability to penetrate clay and enter animal tissue, even assuming one of these weapons managed to breech a mammoth’s tough skin without breaking, Eren says.

Ancient mammoth hunters may have hurled slightly larger Clovis points than the experimental replicas and perhaps launched shots with somewhat greater momentum. Still, sending a spear through an animal’s hide, fat and tissue at an angle that avoided ribs on the way to a fatal rendezvous with internal organs was highly unlikely, Eren says. Unlike the lab setup, presumed mammoth hunters would have taken aim at animals on the move. Spears that lodged in a mammoth’s hide probably felt like a series of stinging pinpricks that could easily have angered the creature and caused it to charge at or stomp on human pursuers.

Try, try again

Replicas of seven points were tested for their ability to penetrate clay blocks used as stand-ins for tougher animal tissue. The bars on the chart denote the number of times the replicas reached various depths in the clay. Outlines of seven Clovis point forms used in the experiment appear above their average penetration depths. Few of the stone projectiles traveled far enough into the targets to have had a chance to cause lethal injury to an actual mammoth.

Average depth that Clovis point replicas pierced a clay target C. ChangC. Chang Source: M.I. Eren et al/J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2021

C. ChangC. Chang Source: M.I. Eren et al/J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2021

Lack of impact

If Clovis people effectively hunted mammoths, their spears would have often hit ribs or other bones, Eren says. Those impacts should have left behind many broken Clovis points at presumed kill sites.

Another experiment supported that expectation. Eren shot 203 replicas of the seven Clovis point types at oak boards, which are not as hard or dense as human or cow ribs. All but three points broke on the first shot. The rest broke on the second shot.

Yet of 93 Clovis points previously found at 15 presumed kill sites, only 12 of 74 discovered among mammoth, mastodon or gomphothere bones had broken, probably after hitting bone, Eren and his colleagues found. In contrast, 10 of 19 Clovis points associated with bison bones — smaller prey with thinner hides likely hunted by Clovis people (SN: 5/13/17, p. 8) — had fragmented due to hard impacts.

Mammoths and their supersized brethren may have fallen prey to Clovis hunters on rare occasions, but the huge beasts would have typically withstood a hail of spears tipped with Clovis points, Eren contends. Even attempts to disable a mammoth by severing tendons in its legs with bladelike Clovis chopping tools attached to handles would probably have failed. In another experiment, Eren swung replicas of such implements at a simulated mammoth foot consisting of a hoof-shaped slab of 5-centimeter-thick clay surrounding beef tendons. Again, in this best-case scenario, chops with Clovis blades sometimes partially cut a tendon but never sliced entirely through one. Often, blades left tendons untouched.

To test whether Clovis tools could disable mammoths, Metin Eren and colleagues, including Kent State archaeologist Michelle Bebber (center left), placed beef tendons against a wooden dowel and then encased them in 5 centimeters of clay to re-create a mammoth foot. Here, Eren (center right) swings a replica Clovis blade tool at the clay foot. Damage inflicted on internal tendons was minimal, sometimes producing partial cuts (far right).M.I. Eren et al/J. Archaeol. Sci Rep. 2021To test whether Clovis tools could disable mammoths, Metin Eren and colleagues, including Kent State archaeologist Michelle Bebber (center left), placed beef tendons against a wooden dowel and then encased them in 5 centimeters of clay to re-create a mammoth foot. Here, Eren (center right) swings a replica Clovis blade tool at the clay foot. Damage inflicted on internal tendons was minimal, sometimes producing partial cuts (far right).M.I. Eren et al/J. Archaeol. Sci Rep. 2021

To test whether Clovis tools could disable mammoths, Metin Eren and colleagues, including Kent State archaeologist Michelle Bebber (center left), placed beef tendons against a wooden dowel and then encased them in 5 centimeters of clay to re-create a mammoth foot. Here, Eren (center right) swings a replica Clovis blade tool at the clay foot. Damage inflicted on internal tendons was minimal, sometimes producing partial cuts (far right).M.I. Eren et al/J. Archaeol. Sci Rep. 2021To test whether Clovis tools could disable mammoths, Metin Eren and colleagues, including Kent State archaeologist Michelle Bebber (center left), placed beef tendons against a wooden dowel and then encased them in 5 centimeters of clay to re-create a mammoth foot. Here, Eren (center right) swings a replica Clovis blade tool at the clay foot. Damage inflicted on internal tendons was minimal, sometimes producing partial cuts (far right).M.I. Eren et al/J. Archaeol. Sci Rep. 2021

Hunting need not have occurred for Clovis points to have been left among mammoth bones. Microscopic damage that has been observed on Clovis points indicates that they could have served as knives to butcher huge beasts that had already died, Eren says. These knives could have been used to cut all sorts of material, from animal hides to edible plants.

Mixed reviews

Eren’s group raises valid doubts about how well Clovis points worked as mammoth killers, says archaeologist Vance Holliday of the University of Arizona at Tucson. Clovis points discovered at alleged kill sites “could have just as well been used for butchering and then left behind.” Scavenged animals could have died of natural causes, accidental injuries or lethal wounds inflicted by nonhuman predators.

No clear evidence of hunting exists at the few sites containing both Clovis points and bones of mammoth or other large animals, Holliday says. For instance, although more than 10,000 Clovis points have been recovered in North America, mostly at campsites and in storage spots called caches, none have been found embedded in bones of big game.

Spears tipped with Clovis points, as well as long segments of bone and ivory shaped into rods with pointed tips found at a few Clovis sites, might have occasionally been thrust by hand at massive prey in order to wound or kill, Holliday speculates.

Human-beast interactions

On this partial map of North America, gold dots designate sites regarded by some researchers as displaying clear evidence of human hunting or scavenging of mammoths and other big game, mostly mastodons.

D.K. Grayson and D.J. Meltzer/J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015 Source: D.K. Grayson and D.J. Meltzer/J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015

D.K. Grayson and D.J. Meltzer/J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015 Source: D.K. Grayson and D.J. Meltzer/J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015

Other archaeologists see no reason to recant traditional views of Clovis points as lethal big-game hunting weapons. Precisely because mammoths were so difficult to kill, Clovis hunters would have thrown or thrust spears at torso areas unprotected by ribs, says Texas State’s Kilby. Such wounds wouldn’t kill right away, but hunters could follow massive prey until bleeding or injuries led to death. That tactic would have resulted in few Clovis points striking ribs and then breaking, consistent with what Eren’s group found.

Such a scenario might have led to the death of a mammoth at a 12,900-year-old site in eastern Wyoming called La Prele. Excavations at La Prele since 1986 have uncovered bones from a mammoth and remnants of a temporary settlement where families gathered to feed off the carcass. Finds include a Clovis point that displays damage from a high-speed impact, says Todd Surovell of the University of Wyoming in Laramie, who directs work at La Prele.

“Clovis points were clearly intended to be hunting weapons,” Surovell says. “I don’t believe for a second that they were primarily used as knives.”

Surprising survival

Determining whether Clovis people scavenged mammoths more often than they hunted them will help to clarify a long-standing debate about whether Stone Age groups drove those creatures to extinction, says archaeologist Ashley Smallwood of the University of Louisville in Kentucky.

Advocates of proficient big-game hunting by Clovis people and by even earlier groups in northern Asia suspect that humans killed off mammoths within a few hundred years of first encountering them.

Eren and other researchers think it more likely that those animals died out as ancient shifts to a warmer, wetter climate shrank the grasslands on which the animals lived. Ancient DNA has already supported a similar scenario of extinction by climate change for Siberian woolly rhinos around 14,000 years ago (SN: 9/12/20, p. 9). A recent study, also based on ancient DNA, suggests the same for mammoths.

Evolutionary geneticist Yucheng Wang of the University of Cambridge and his colleagues analyzed plant and animal DNA extracted from 535 sediment samples from the Arctic spanning roughly the last 50,000 years.

Based on that genetic evidence, mammoths survived in Arctic parts of North America until about 8,600 years ago, in northeast Siberia until around 7,300 years ago and in north-central Siberia until as late as about 3,900 years ago, the researchers reported October 20 in Nature. Thus, mammoths coexisted with people for several thousand years or more in those regions. That means in North America, mammoths outlasted the Clovis culture by nearly 5,000 years. An unexpectedly late survival of plants suited to grassland and tundra areas appears to have enabled mammoths to persist longer than previously estimated, the researchers say.

Woolly mammoths died out in various parts of Eurasia over many thousands of years before meeting their final end in the Arctic locales studied by Wang’s group, say ecologist Damien Fordham of the University of Adelaide in Australia and his colleagues. Computer simulations based on ancient DNA, fossil and climate data suggest that rising temperatures and growing human populations led to mammoth die-offs in Europe and Asia starting around 19,000 years ago and in much of Asia starting roughly 15,000 years ago, Fordham’s team reported November 5 in Ecology Letters.

Similar to Wang’s ancient DNA findings, Fordham’s computer simulations suggest that woolly mammoths survived in still-frigid Siberia until roughly 3,000 years ago.

Rapid movements of ancient human groups across Eurasia disrupted woolly mammoths’ ability to move among areas once plentiful with food and water, Fordham’s group suggests. That, more than hunting, hastened the huge beasts’ demise, the researchers suspect.

Perhaps North American mammoth extinction similarly played out in stages. Maybe human hunters played only a minor role in that process. Whatever the case, mammoths, it seems, are as capable of throwing curves at scientists as Clovis people and their stone points.

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.

Subscribe or Donate Now