For the first time since 1872, rare funerary objects believed to have come from the Daisenryo Kofun have been recovered.

The Daisenryo Kofun is Japan’s largest Kofun tomb, located in the Osaka Prefecture of Japan. It is thought to be the burial place of Emperor Nintoku, the 16th Emperor of Japan who reigned from AD 313 to 399.

The tradition of constructing Kofun tombs started during the late 3rd century AD, with the most common form being the “zenpō-kōen-fun” – distinctively shaped keyhole mound with one trapezoid end and one circular end.

The funerary objects were acquired by Kokugakuin University from an art dealer in 2024, which came from the private collection of Masuda Takashi, a Japanese industrialist and art collector who lived during the mid-19th to mid-20th century.

Takashi likely acquired the objects from Kaichiro Kashiwagi, a builder who conducted restoration works on the Daisenryo Kofun following a landslide in 1872, exposing part of the stone burial chamber.

While Kashiwagi documented what he found inside (knives, armour, helmets, sword fittings, and glassware), he backfilled the chamber as exploratory excavations was prohibited.

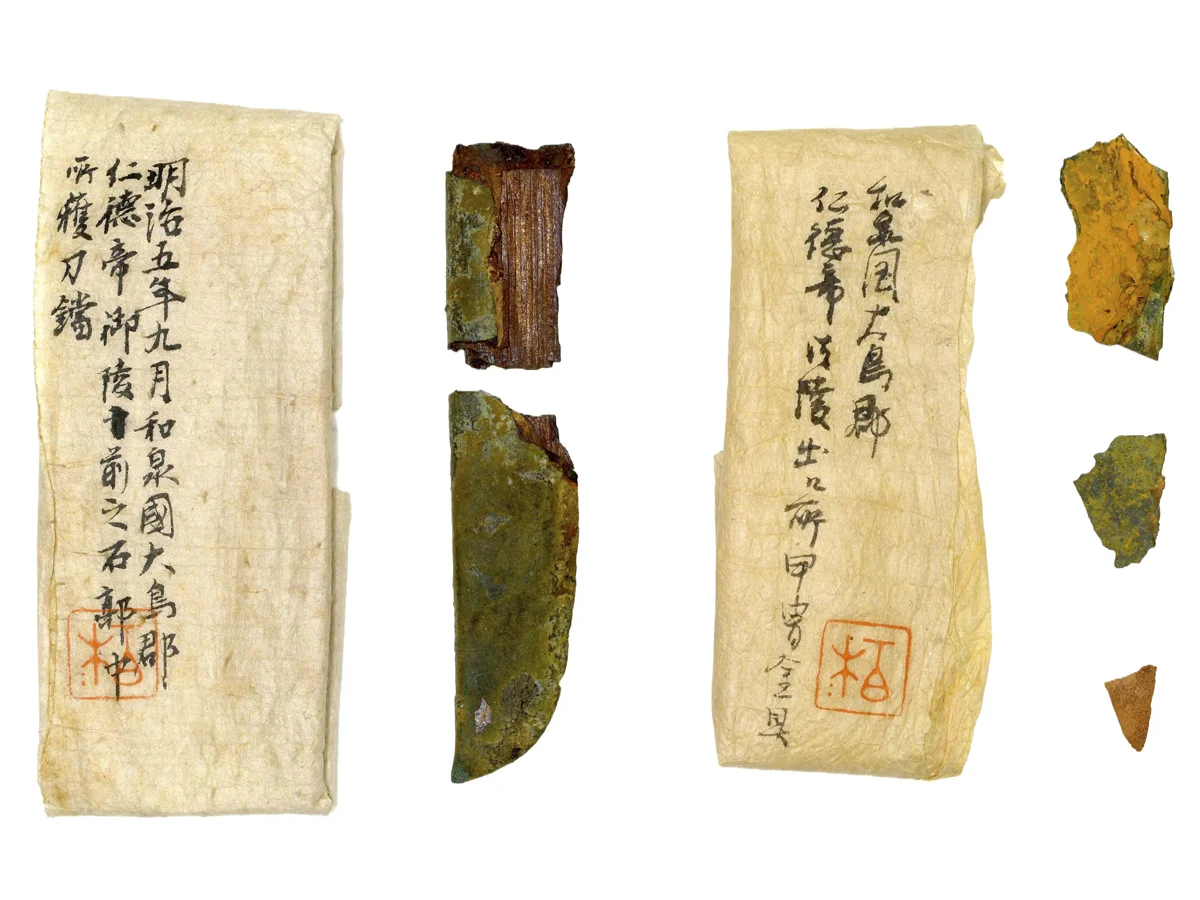

We now know that he must have looted some of the tomb contents, as the recently recovered objects have the original paper wrappings with the handwritten labels and seal of Kaichiro Kashiwagi.

These include a gold-plated ceremonial knife and three gilded armour fragments, marking the first physical evidence from the tomb to be examined by modern science.

The knife features an iron blade housed in its original Japanese cypress sheath, encased in a gold-plated copper plate only 0.5 mm thick and fastened with five silver rivets. Archaeologists believe it was crafted for ceremonial use, noting no other gold-plated small knives from 5th-century kofun burials are known.

The armour fragments, 3 to 4 cm in size, were found to be iron coated directly with gold, contradicting earlier 19th-century illustrations that depicted gold-plated copper. This finding, experts say, refines our understanding of elite craftsmanship during the Nintoku court’s reign.

“These were not battlefield weapons,” said archaeologist Taro Fukazawa of Kokugakuin University. “They were prestige items, created solely as offerings, demonstrating the immense political and economic power of the imperial court.”

Header Image Credit : Google Earth – Map data ©2025 Google

Sources : Kokugakuin University