The Juno mission finding offers deeper insights into the long-debated internal structure of the gas giant Jupiter.

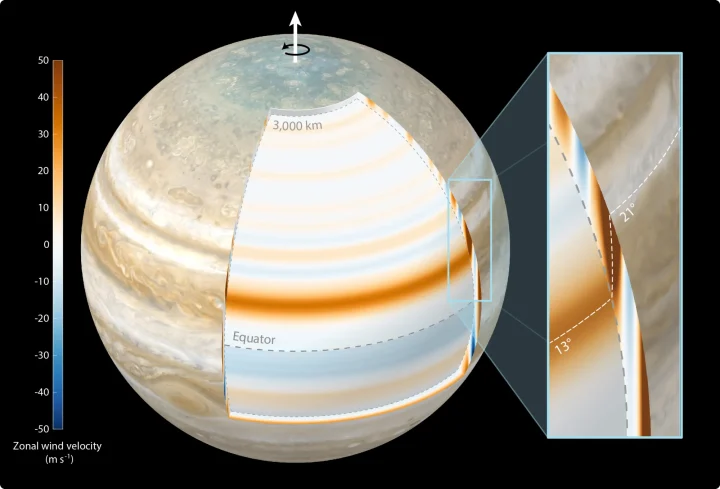

Gravity data collected by NASA’s Juno mission indicates Jupiter’s atmospheric winds penetrate the planet cylindrically, parallel to its spin axis. A paper on the findings was recently published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

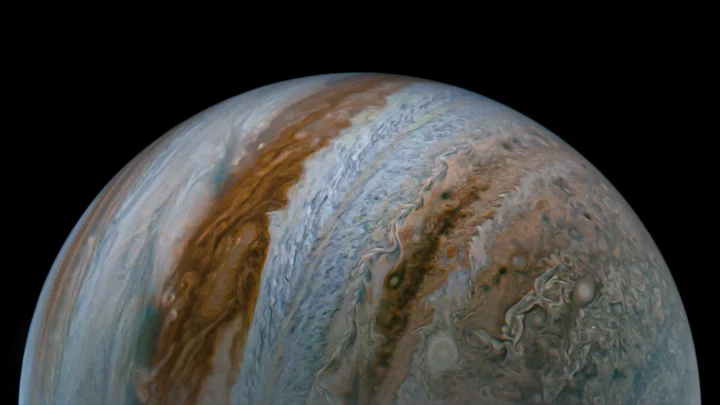

NASA’s Juno captured this view of Jupiter during the mission’s 54th close flyby of the giant planet on Sept. 7. The image was made with raw data from the JunoCam instrument that was processed to enhance details in cloud features and colors. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS Image processing by Tanya Oleksuik CC BY NC SA 3.0

The violent nature of Jupiter’s roiling atmosphere has long been a source of fascination for astronomers and planetary scientists, and Juno has had a ringside seat to the goings-on since it entered orbit in 2016. During each of the spacecraft’s 55 to date, a suite of science instruments has peered below Jupiter’s turbulent cloud deck to uncover how the gas giant works from the inside out.

One way the Juno mission learns about the planet’s interior is via radio science. Using NASA’s Deep Space Network antennas, scientists track the spacecraft’s radio signal as Juno flies past Jupiter at speeds near 130,000 mph (209,000 kph), measuring tiny changes in its velocity – as small as 0.01 millimeter per second.

Those changes are caused by variations in the planet’s gravity field, and by measuring them, the mission can essentially see into Jupiter’s atmosphere.

Such measurements have led to numerous discoveries, including the existence of a dilute core deep within Jupiter and the depth of the planet’s zones and belts, which extend from the cloud tops down approximately 1,860 miles (3,000 kilometers).

Doing the Math

To determine the location and cylindrical nature of the winds, the study’s authors applied a mathematical technique that models gravitational variations and surface elevations of rocky planets like Earth. At Jupiter, the technique can be used to accurately map winds at depth.

Using the high-precision Juno data, the authors were able to generate a four-fold increase in the resolution over previous models created with data from NASA’s trailblazing Jovian explorers Voyager and Galileo.

This illustration shows that Jupiter’s atmospheric winds penetrate the planet cylindrically and parallel to its spin axis. The most dominant jet recorded by NASA’s Juno is shown in the cutout: The jet is at 21 degrees north latitude at cloud level, but 1,800 miles (3,000 kilometers) below that, it’s at 13 degrees north latitude. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI/SWRI/MSSS/ASI/ INAF/JIRAM/Björn Jónsson CC BY 3.0

“We applied a constraining technique developed for sparse data sets on terrestrial planets to process the Juno data,” said Ryan Park, a Juno scientist and lead of the mission’s gravity science investigation from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. “This is the first time such a technique has been applied to an outer planet.”

The gravity field measurements matched a two-decade-old model that determined Jupiter’s powerful east-west zonal flows extend from the cloud-level white and red zones and belts inward.

But the measurements also revealed that rather than extending in every direction like a radiating sphere, the zonal flows go inward, cylindrically, and are oriented along the direction of Jupiter’s rotation axis. How Jupiter’s deep atmospheric winds are structured has been in debated since the 1970s, and the Juno mission has now settled the debate.

“All 40 gravity coefficients measured by Juno matched our previous calculations of what we expect the gravity field to be if the winds penetrate inward on cylinders,” said Yohai Kaspi of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, the study’s lead author and a Juno co-investigator. “When we realized all 40 numbers exactly match our calculations, it felt like winning the lottery.”

Along with bettering the current understanding of Jupiter’s internal structure and origin, the new gravity model application could be used to gain more insight into other planetary atmospheres.

Juno is currently in an extended mission. Along with flybys of Jupiter, the solar-powered spacecraft has completed a series of flybys of the planet’s icy moons Ganymede and Europa and is amid several close flybys of Io. The Dec. 30 flyby of Io will be the closest to date, coming within about 930 miles (1,500 kilometers) of its volcano-festooned surface.

“As Juno’s journey progresses, we’re achieving scientific outcomes that truly define a new Jupiter and that likely are relevant for all giant planets, both within our solar system and beyond,” said Scott Bolton, the principal investigator of the Juno mission at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio.

“The resolution of the newly determined gravity field is remarkably similar to the accuracy we estimated 20 years ago. It is great to see such agreement between our prediction and our results.”