Monica Ngambi was born in Zambia’s copper-rich northern province as the nation declared its independence on 24 October 1964. For 60 years, she has lived by the large copper mines on which the independent country tied its economic prosperity.

But as miners scarred the land to extract the metal – at times polluting water sources and destroying farmland – local people have reaped few of the benefits.

Today, Ngambi doesn’t earn enough selling groundnuts and cassava at a market in the mining town of Chingola to feed her family.

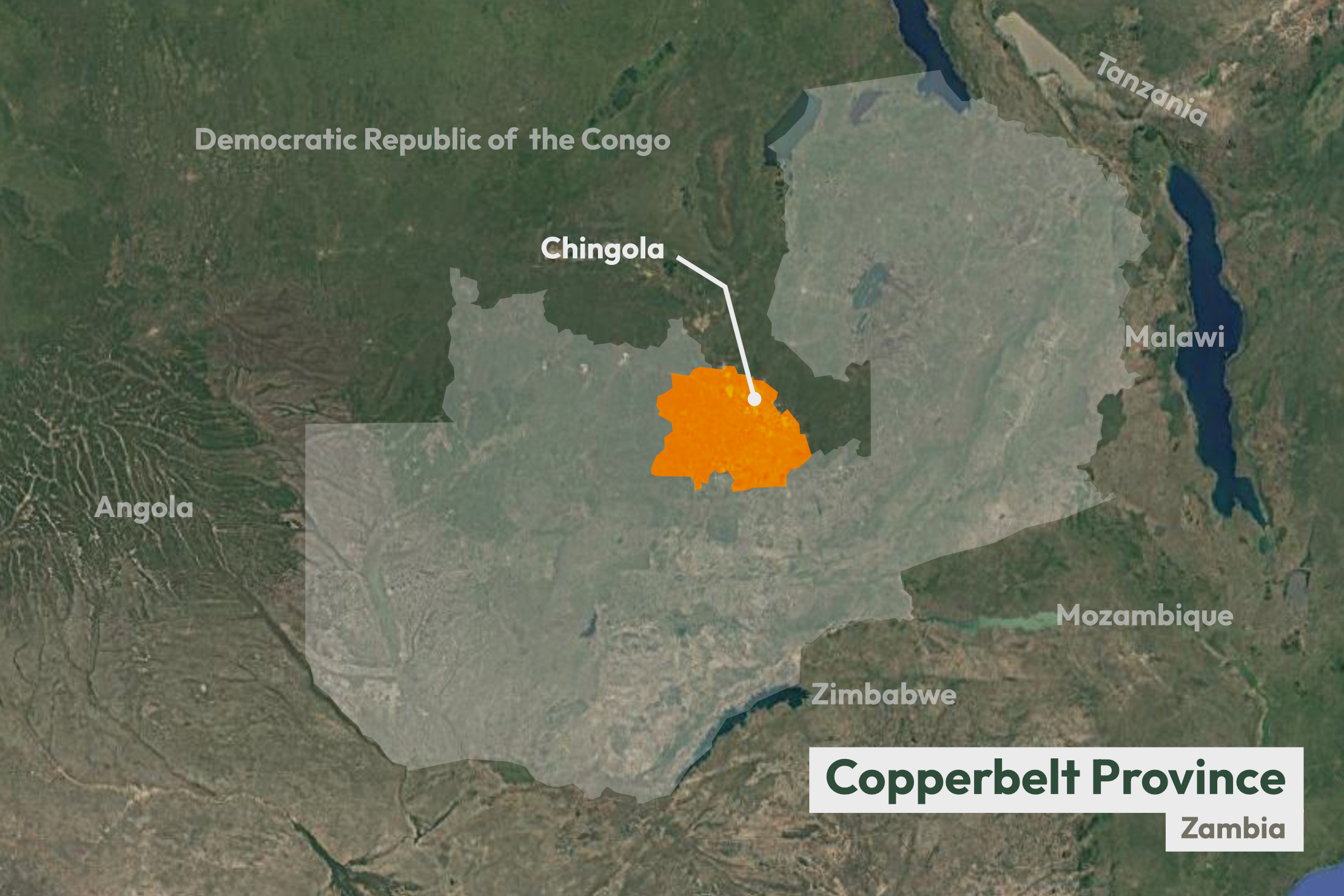

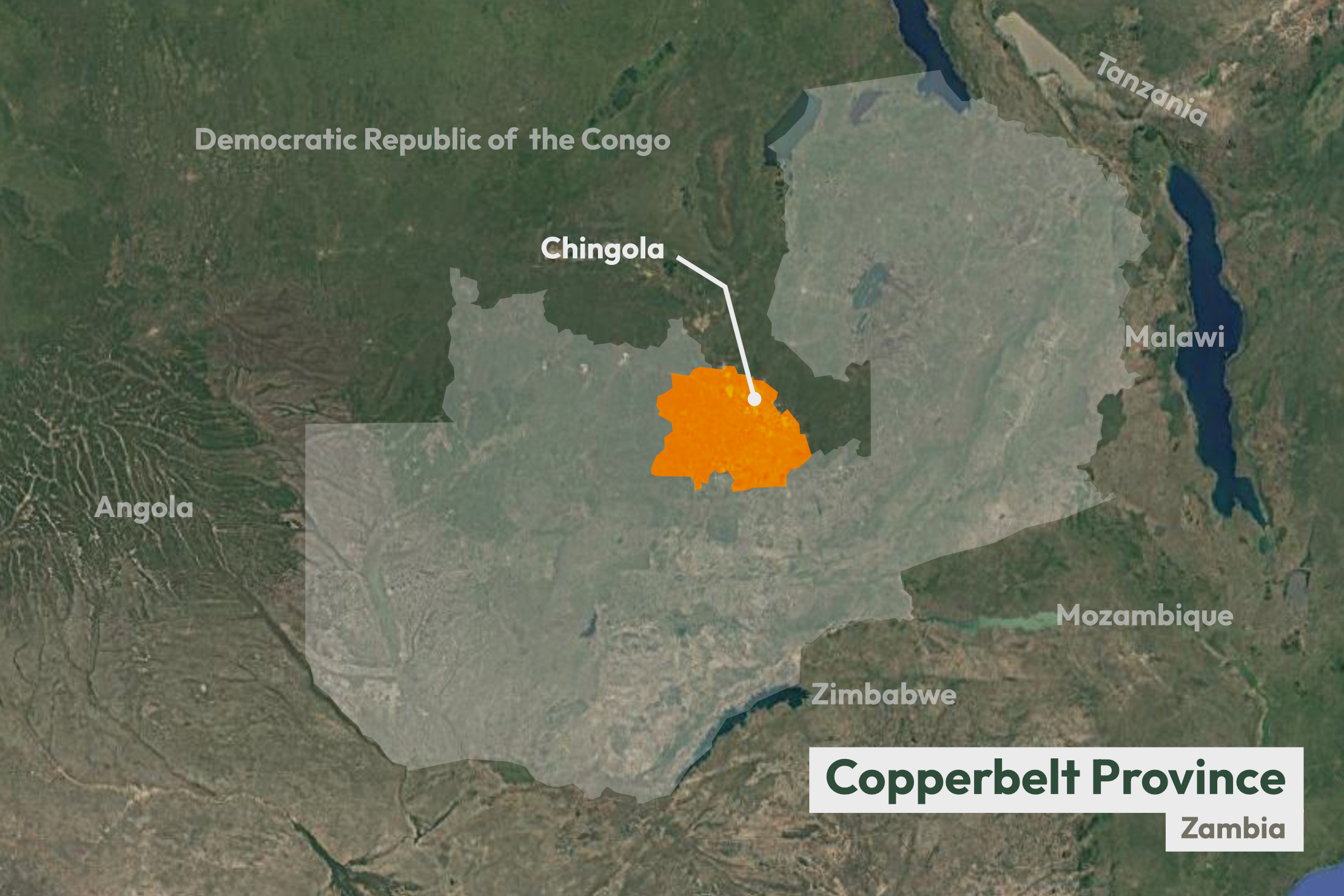

Chingola sits atop one of the world’s largest reserves of copper – a reddish metal that is particularly good at conducting heat and electricity and is pivotal to the world’s clean energy transition.

But Ngambi, who barely earns 100 Zambian Kwacha (about $4) a week, survives thanks to a cooperative of market traders, who pool funds to buy food. Her neighbourhood doesn’t have access to clean water, and local people buy chlorine to purify the water from shallow wells.

“We don’t know how our children’s grandchildren will live. We need… a real future,” she told Climate Home News.

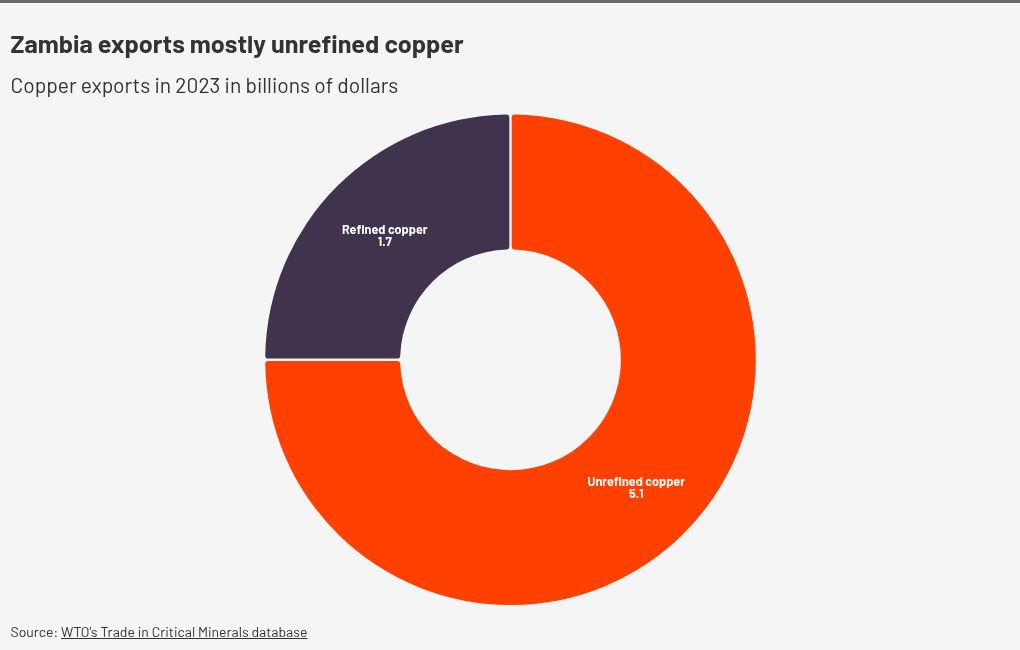

In 2022, Zambia was the world’s top exporter of raw copper, selling $6.6 billion worth of the unprocessed metal. The same year, nearly two-thirds of Zambia’s population lived in extreme poverty.

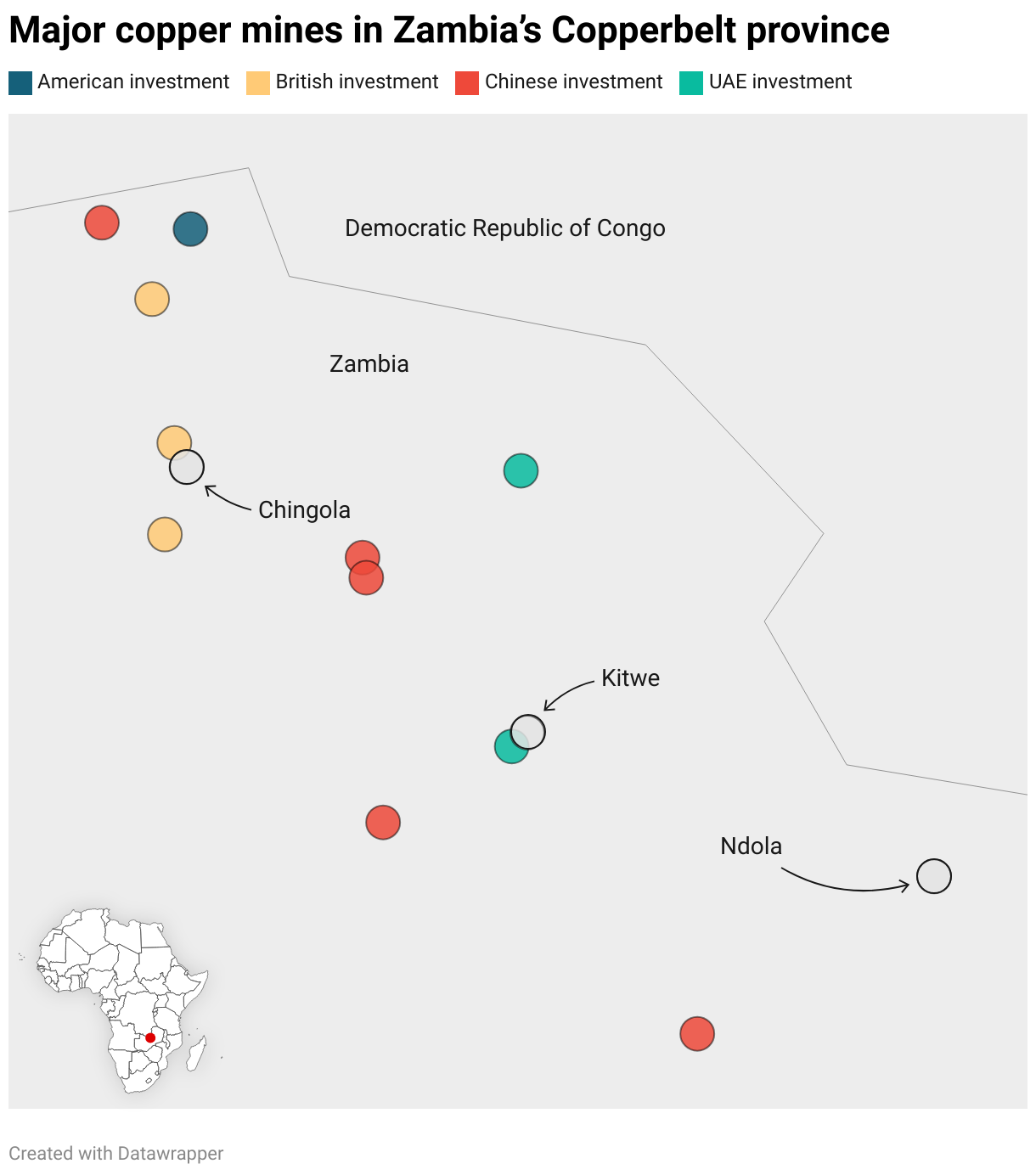

Intense Chinese and Western interest in Zambia’s copper resources, however, has renewed the promise of using the mineral to lift people out of poverty, free the country from debt and meet its development goals. Mining investments have soared as the government seeks to massively boost copper output and add value to its resources by processing the metal for the electric vehicle (EV) industry.

But analysts warn that delivering on the ambitious plans while ensuring local people benefit requires the nation to address its large informal mining economy, end an opaque tax regime and deliver legislative efforts to better regulate the sector.

In Chingola, that will mean clamping down on a dangerous – and sometimes violent – illegal industry that sees gangs of youths scavenge and supply raw copper to small-scale Chinese processors.

Open for business

Zambia is Africa’s second-largest copper producer after the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Its economy depends on the metal, which accounts for around 70% of its export earnings.

Moving away from climate-warming fossil fuels and slashing greenhouse gas emissions requires the electrification of global power, transport and heating systems – none of which is possible without copper.

Copper is needed to manufacture everything from EV motors and batteries to solar power wiring and cables for energy storage and distribution networks.

As a result, soaring demand for the metal is soon expected to outstrip supply. The International Energy Agency has warned the world could see a 30% copper deficit by 2035, with more investments required to scale copper production than any other transition mineral.

To capture a slice of this booming market, the Zambian government has set out highly ambitious plans to quadruple copper output to three million tonnes annually by 2031. It recently launched a high-resolution aerial geological survey of the country to determine mineral deposits across its ten provinces – the first comprehensive mapping exercise since 1972.

To deliver on its growth plans, the government is wooing international investors to inject capital into the country’s ageing mining infrastructure, with some success.

Between 2022 and the end of June 2024, Zambia received mining investment pledges exceeding $7 billion for new and expansion projects, according to the World Bank.

Among Zambia’s flagship new investors is KoBold Metals, an AI-powered critical mineral exploration start-up, which is backed by Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos and is mooted to spend upwards of $2 billion on mining a vast copper deposit it recently discovered north of Chingola.

Over a few days in October, in a leafy neighbourhood of the capital Lusaka, government officials, investors, mining experts and company representatives gathered for the Zambia Mining and Investment Insaka – the country’s first international mining conference.

The event took stock of the impacts of a century of mining and pitched the nation’s mining opportunities to global mining companies and investors.

“We believe we have natural resources that can change the economy of this country,” Paul Kabuswe, Zambia’s mines minister, told the conference. But years of repeated policy changes created uncertainty in the mining sector, which hurt investments, he said. “All we needed were good policies that make investors comfortable,” said Kabuswe.

Since coming to power in 2021, the government has sought to develop a tax regime which is “stable, predictable and competitive“ to drive investments and scale mining output.

Mining companies have responded positively. Chinese firms, which have invested more than $3.5 billion in Zambia’s mining industry since the late 1990s, are planning to invest an additional $5 billion into the sector over the next five years, Li Zhanyan, chair of the Chinese Mining Enterprises Association, told the conference.

Shadow mines

The copper-rich soils under Chingola gave the province its name: the Copperbelt.

For close to a century, the metal was extracted in some of the continent’s largest open-pit mines.

After Zambia’s independence, copper mining companies were gradually nationalised. Revenues from copper exports were used to boost public and development spending: the sector created jobs, and helped fund hospitals, healthcare facilities and education scholarships.

Chingola thrived. “Even those who didn’t work at the mines felt secure,” remembered Ngambi.

But by the early 1990s, President Frederick Chiluba had sold off the mines to private companies, including foreign firms, to withstand a long-term decline in copper prices and an economic depression. Jobs were cut and Chingola’s fortunes faded.

Whether renewed large-scale foreign investments can help clean up and modernise Zambia’s mining sector remains to be seen. Today, the country’s copper extraction relies partially on a parallel informal mining economy, fuelled by high youth unemployment, which has grown up to sustain the livelihoods of thousands of people.

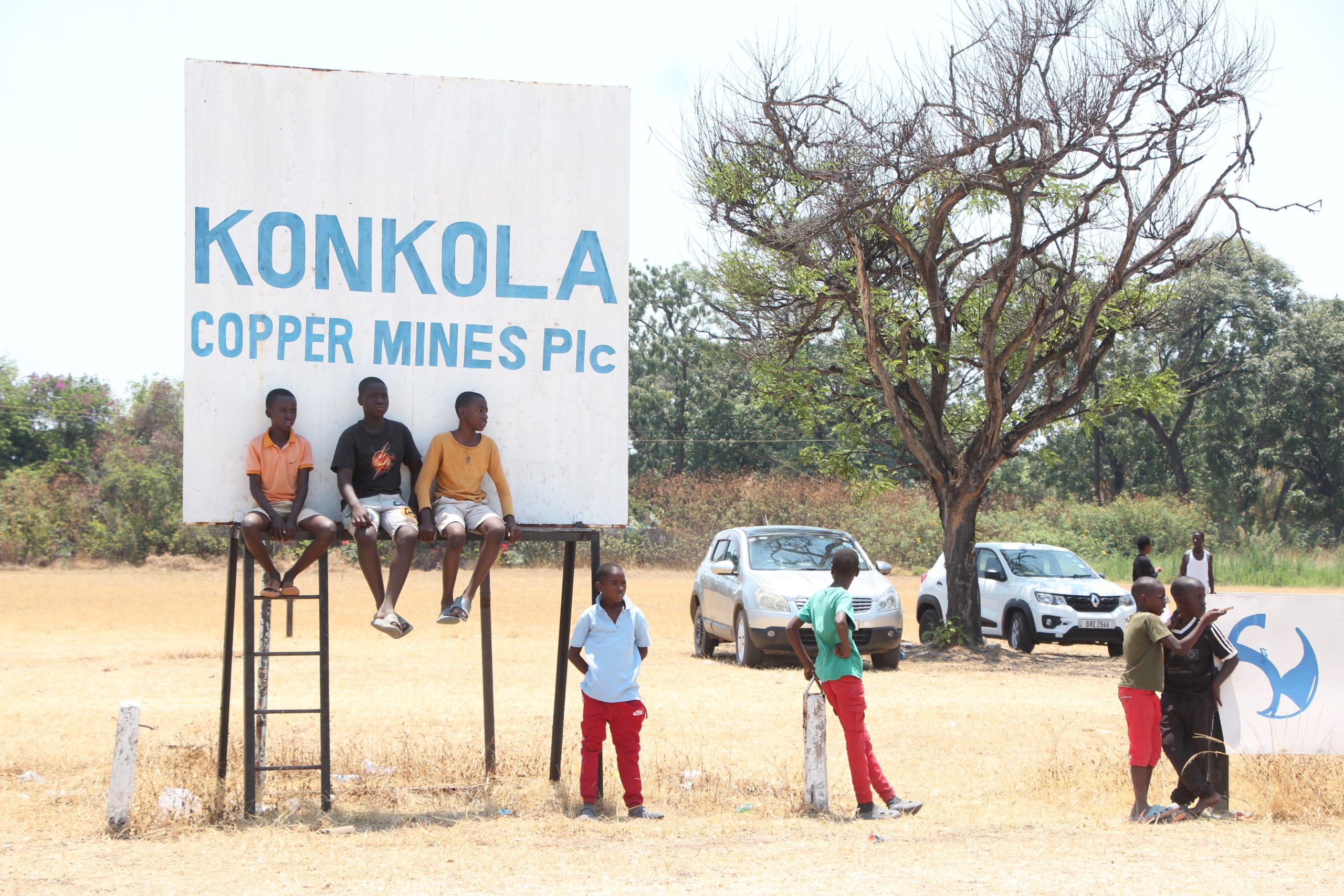

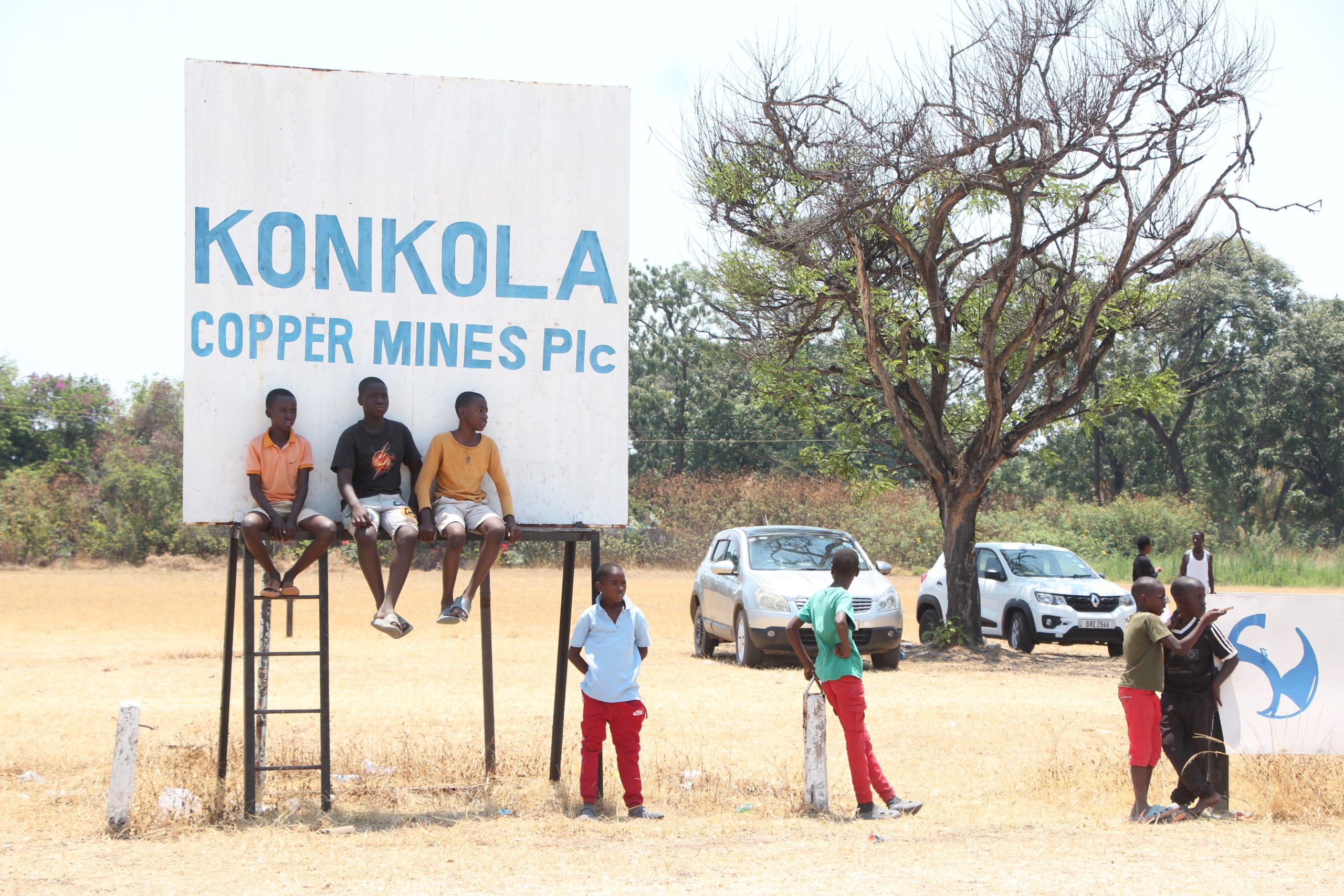

Across the Copperbelt, gangs of young artisanal miners, known as Jerabos, scavenge copper scraps and mining waste known as tailings – dangerous work, which often turns deadly.

Without formal training or safety gear, the Jerabos dig tunnels hundreds of metres underground with minimal lighting and no structural reinforcements. They risk exposure to toxic waste and death if the tunnels cave-in.

an illegal mining gang in Chingola

an illegal mining gang in Chingola

Over a 10-day period when Climate Home was reporting in the area in October 2024, ten men from Chingola died in both legal and illegal mining operations, local police officers told us.

Edward Kapungwe joined Chingola’s Jerabos at just 20 years old. Danger, he told Climate Home, is part of the job. But the work pays.

“We have a ready market – the Chinese,” he said, describing a network of buyers, some of whom operate unauthorised and makeshift smelters under trees.

This informal economy often fuels gang violence in Chingola, as rival groups compete for control over illegal copper trading networks, leading to frequent clashes over mining sites and smuggling routes.

To tap into this vast workforce, the government wants to formalise the work of thousands of young illegal miners.

“We are working towards giving artisan licences to the youths so that they can legally mine and contribute to the tax base,” Raphael Chimupi, Chingola’s district commissioner, told Climate Home.

The increasing presence of mini processing plants, often run by Chinese companies, which purchase copper ore from unlicensed miners, indirectly encourages illegal mining activities, he added.

In response, the government is advancing legislation to prohibit the purchase of illegally mined copper through a licensing system which will help establish a more regulated and transparent supply chain, Chimupi said.

But campaigners at Transparency International have raised concerns the government’s dual approach of reforming the informal sector while turbocharging production could undermine governance reforms.

A node in the EV battery supply chain

To better capitalise on its resources, the mineral-rich but debt-laden nation has set out plans to shift away from exporting raw copper and to refine minerals domestically.

The move is part of Zambia’s plans to process its copper into high-value battery-grade metals, becoming a vital node in the continent’s aspiring EV supply chain.

In late 2022, the US, Zambia and the DRC agreed to support the development of a joint EV battery supply chain across the two African nations that would cover mining, processing, manufacturing and assembly, sparking hope for further value addition on their soil.

The DRC holds abundant reserves of copper and 70% of the world’s reserves of cobalt, another pivotal battery material.

While US President Donald Trump’s support for the initiative agreed under his predecessor is uncertain, Kabuswe told the mining summit that Zambia and the DRC are working to develop a battery manufacturing supply chain. “This transition would create jobs and bring substantial economic benefits to our communities,” he said, calling for the negotiations with the DRC to move forward.

Chingola is earmarked as a potential site for an EV battery production plant and the plans have brought hope to the mining town.

Mulenga Pascal Bwalya arrived in Chingola in 1965 a young and ambitious man with a job in the copper mining industry. Decades later and now retired, Bwalya said the rise of EVs could mark a U-turn in Zambia’s struggle to add value to its resources.

“Copper is one of the valuable components of electric vehicles. I pray that those will be assembled here one day, ensuring technology transfer, creating employment for our people and fostering a prosperous Zambia,” he said.

From raw resources to processed wealth

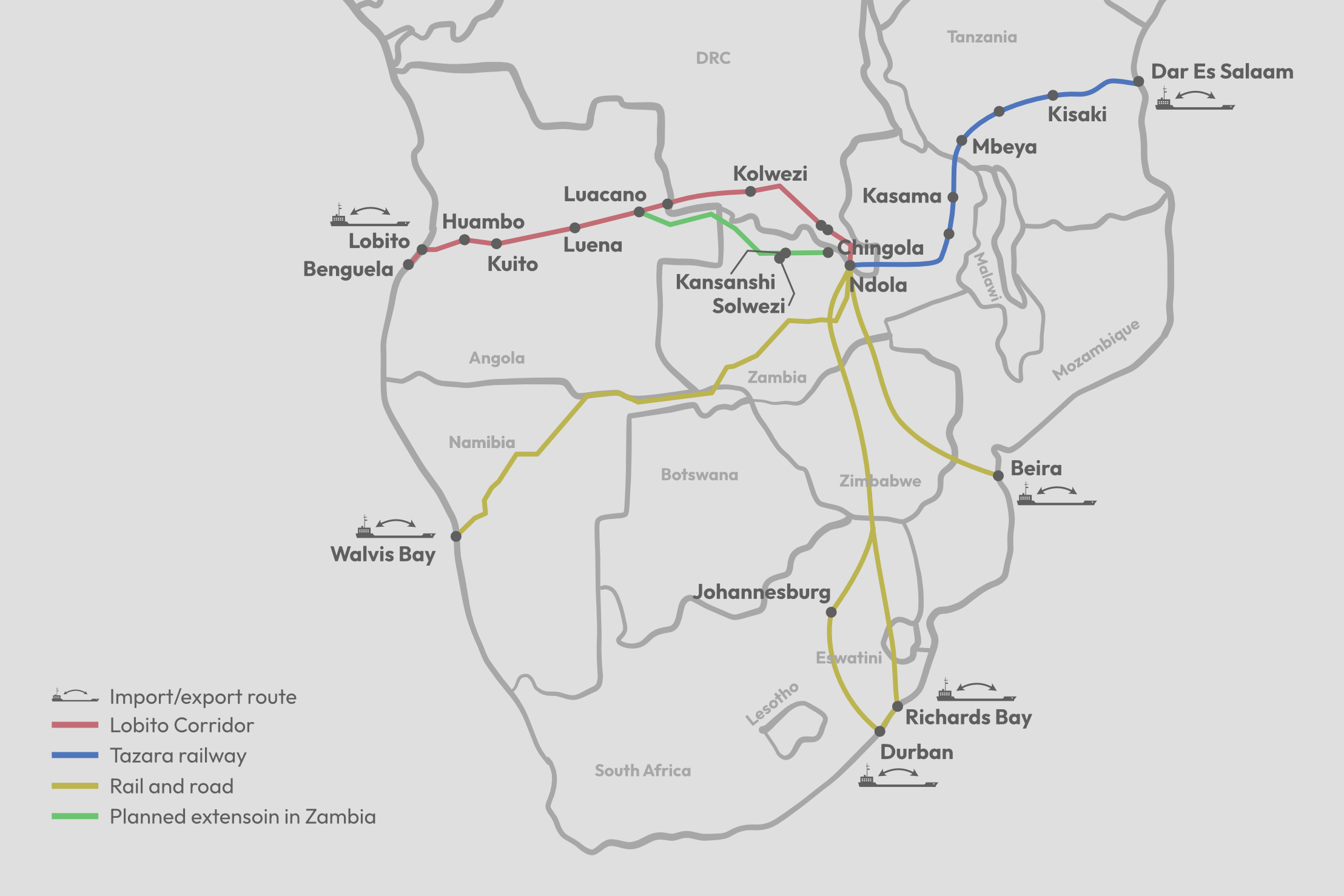

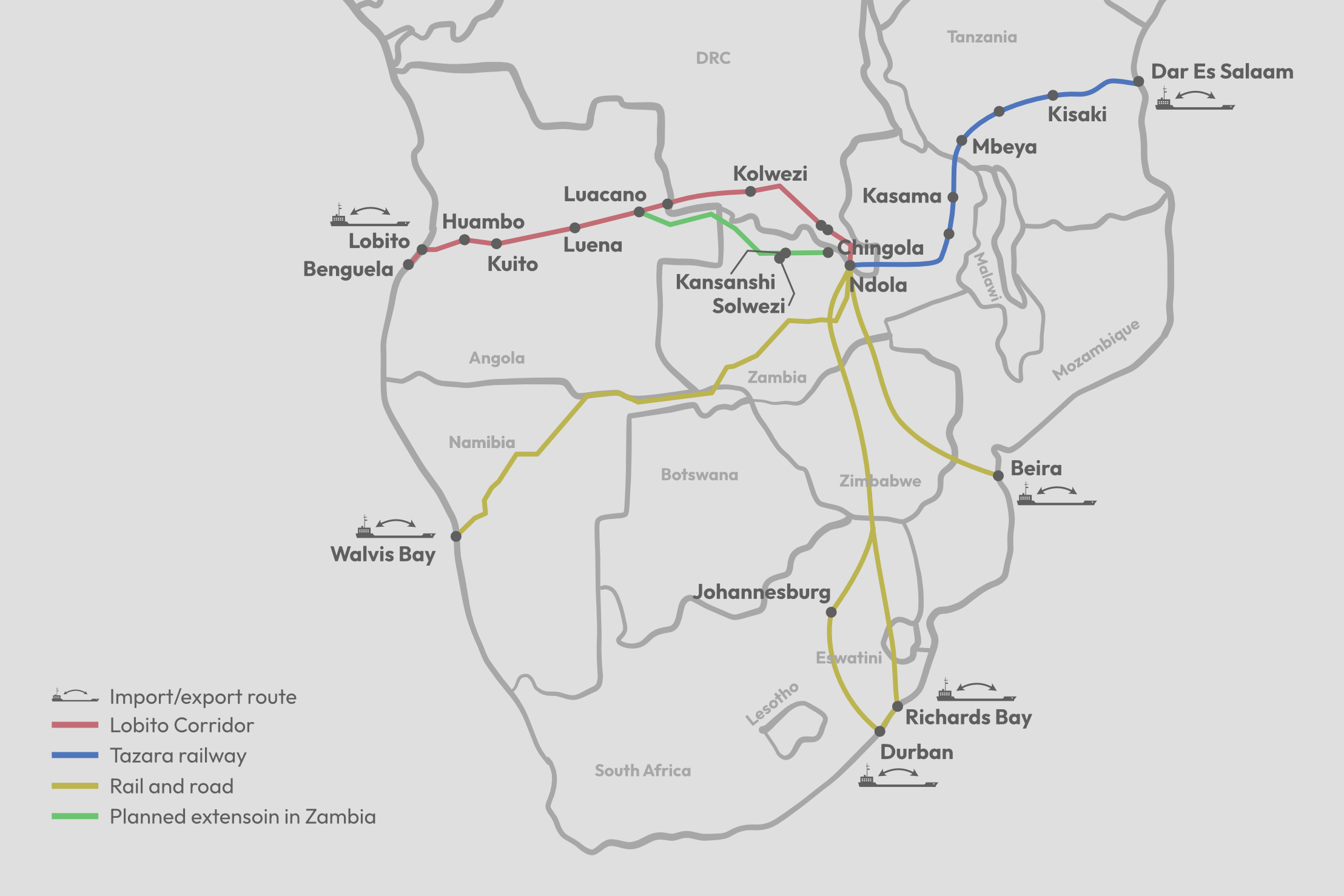

Anticipating a jump in production, the US and China are reviving two major railway projects to join the landlocked nation to the sea and get Zambia’s mineral resources to their own markets.

To the west, the US is supporting the Lobito Corridor, a massive railway project linking the DRC to the Angolan port of Lobito, which previously received Chinese investment. A new 830-kilometre section would extend the railway to Chingola in Zambia’s Copperbelt.

The railway, which has received financing exceeding $1 billion, has been designed to create a faster route to export DRC and Zambia’s minerals. It will reduce the journey time from 45 days using the existing road corridor to the South African port of Durban to just seven days, lowering export costs and cutting emissions, according to the project’s developers.

The Biden administration backed the rehabilitation of the Angolan section of the railway with a $553-million loan but it is unclear to what extent Trump will support the project. Yet, KoBold Metals has already committed to use the railway to export 300,000 tons of copper and related freight annually.

To the east, China is revamping the Tazara railway, which links Zambia’s Copperbelt to the Tanzanian port of Dar es Salaam. Plans to link the two rail projects would create a huge network of infrastructure to facilitate trade across the continent.

Both projects have the potential to massively boost Zambia’s copper exports. But experts caution they could serve as fast lanes for exporting raw minerals if the resources are not processed domestically before they are shipped.

“The development of the Lobito Corridor and the modernisation of Tazara are important for Zambia’s mining sector. But we must ensure that these projects focus on refining and value addition,” Ashu Sagar, president of the Zambia Association of Manufacturers, told the mining conference.

“If these transport corridors are used solely to export raw copper, we risk losing out on the full economic potential that comes with value-added products,” he said.

KoBold didn’t answer Climate Home’s questions about whether it plans to process the copper it is set to start commercially mining in 2026 in the country.

An estimated 20% of Zambia’s copper is processed domestically, according to Zamefa, the nation’s sole copper processor. Raw copper is exported for processing, mostly to China, which refines the majority of the world’s minerals for producing clean energy technologies.

But some plans are afoot to process minerals in Zambia, including Africa’s first cobalt sulphate refinery to supply battery grade cobalt for EVs.

For the many, not the few

Civil society groups in Zambia have long demanded more accountability in the country’s mining sector so it maximises revenues, benefits local communities and helps finance local development.

OpenNet For All Zambia, a local NGO, has pointed to secretive mining contracts and an opaque tax regime with loopholes allowing companies to underreport earnings as part of the problem that keeps wealth from communities.

“Mining must contribute to the social fabric, not just corporate profits,” Sipho Mwanza, the NGO’s executive director, told Climate Home.

“These opaque systems make it difficult for the government to monitor and collect the fair share of revenues from the sector, often resulting in substantial revenue losses for the country,” he warned.

“Zambia’s mining sector needs to be accountable,” agreed Edward Lange, of the Southern Africa Resource Watch, which monitors resource extraction in the region. He told Climate Home that fair taxation policies, stricter corporate social responsibility laws and local value addition are essential to retain more mining wealth in the country.

Lange welcomed the government’s legislative push to create a more transparent and better regulated mining sector.

This includes plans to reduce foreign dominance, increase Zambian ownership through a local content requirement, and ensure the country benefits more from its vast mineral resources by establishing a public investment company that will control at least 30% of mineral production from future mines.

“By focusing on these fair and equitable policies, Zambia has the potential to improve its national economy, increase job creation, and ensure that its resources benefit the local population while still attracting foreign investment,” said Lange.

“Our resources should not be a curse,” he added, “but uplift our communities.”

Main image: Artisanal miners look for copper in mining waste