Campaigners hold a static, quiet protest – and observers say human rights language and finance are tripping up the COP29 gender negotiations

This article will be updated throughout the day and an edited version will be sent out each evening as a newsletter – you can sign up here.

Protest – but do not disturb

From gloomy Glasgow to sunny Dubai, climate marches on the middle weekend have been a constant at COPs – but their character has shifted in recent years. The Glasgow event in 2021 was the biggest, bringing together over 100,000 people who marched through the city in the pouring rain. The Dubai one last year was large too, but with a key difference: it happened inside the venue, so no one without a UN badge could join.

The same thing happened the year before, at COP27 in the Egyptian resort of Sharm el-Sheikh. And this COP in Baku marks the third where demonstrations are being held inside the venue due to the summit being hosted by an authoritarian government.

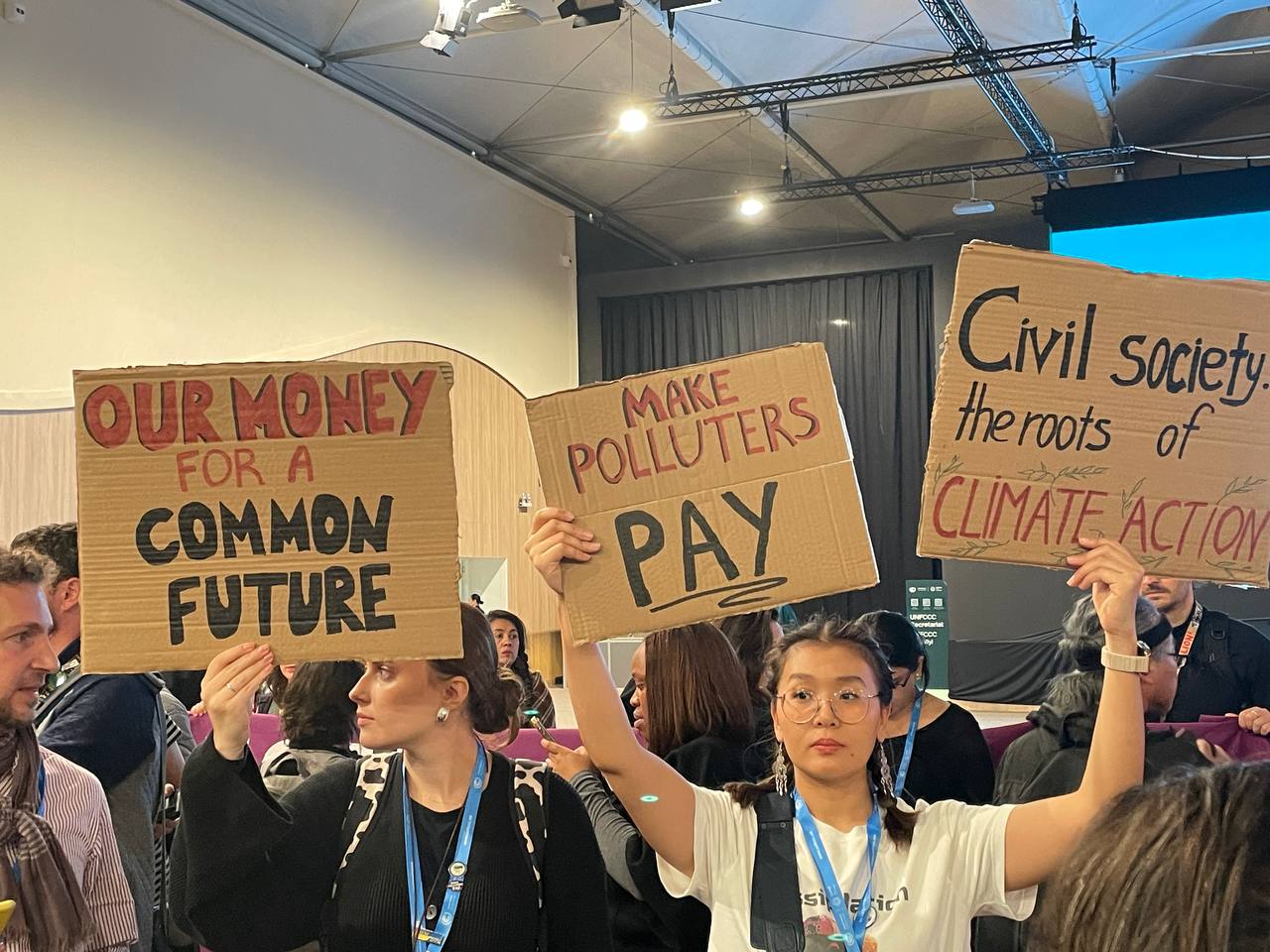

Protestors inside COP29. This marks the third climate summit where protests have happened inside the venue. Photo: Climate Home News

This year there was no actual march. Instead, activists held a rally inside a large plenary room – and then made a human chain outside in the space between plenary rooms. There no chanting was allowed, only humming and finger-snapping.

Climate Home understands that singing and chanting is not allowed close to negotiating rooms inside the COP venue, which is managed by the United Nations, in order not to disturb the discussions. That is one of the UNFCCC and UN Department of Security and Safety rules – as well as not naming any countries or using flags.

Campaigners said they were informed by the UNFCCC team that the layout of this COP made it difficult to hold a march, leaving only the option of walking through the stadium where it’s located – which they refused as it would have limited the visibility of their action. The corridors between halls are tight and a march could have blocked the passage of people.

But being cooped up inside a plenary room wasn’t ideal either. Eduardo Giesen, Latin America coordinator of the Global Campaign to Demand Climate Justice (DCJ), said it was like “talking between ourselves”.

Inside the plenary room campaigners were allowed to chant. Photo: Climate Home News

Once outside, the hundreds of participating protestors held up banners calling for increases in climate finance, a fair transition away from fossil fuels, gender justice, peace and more.

In the past week, campaigners’ complaints about the civil space shrinking at COP have been on the rise.

One representative from Climate Action Network Latin America said they had been prepared to face a COP in Azerbaijan, which according to Human Rights Watch “remains hostile to dissenting voices, targeting government critics and political opponents”. But now they are here and see the limitations, they feel “solidarity is prohibited”, they told Climate Home.

Gender talks going nowhere

All eyes may be on finance at COP29, but negotiators are also fighting about an overlooked decision on gender that remains gridlocked after the first week of talks.

Established back at COP20, the Lima Work Programme is meant to provide guidelines for gender-responsive climate policies, which then informs a Gender Action Plan (GAP) every five years. The work programme is due to be renewed here in Baku, aiming to advance gender balance at the UN climate talks and integrate gender considerations more effectively into climate action.

But negotiations have been lengthy and difficult. The main sticking points are human rights language and finance for closing the gender gap in climate action. Observers say Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and the Vatican – among other socially conservative countries – have been the main blockers.

UN action on gender and climate faces uphill climb as warming hurts women

Divisions are so bad that talks could collapse. Two negotiators told Climate Home that there’s a risk of reaching no agreement and pushing the decision to next year’s COP.

Negotiators told us they had hoped for more help from the presidency, but said Azerbaijan has not prioritised the issue. Earlier in the year, the COP presidency also came under fire for announcing a COP29 committee with 28 members and no women. They later included 12 women after getting backlash from observers.

This imbalance is not uncommon: at last year’s COP, only 15 of 133 world leaders present were women. This year, the number dropped further, representing just 8%.

Women are disproportionately affected by climate change, as they often work in vulnerable industries like small-scale farming and bear the burden of household responsibilities like collecting water, which becomes even heavier after disasters.

African group slams “lack of significant progress”

The chair of the African group of negotiators Ali Mohamed has raised concerns over the “lack of significant progress” as week one of COP29 comes to end. He said the delays risk moving into the next week but maintained that Africa is clear on its objectives and will not reach any agreement for the sake of it.

At a briefing with civil society today, Mohamed said the delayed progress on finance could result in a “stalemate”. He maintained Africa’s support for developing countries joint demand for a $1.3 trillion goal and said at least half of this should be in grants and concessional finance.

Speaking on the international financial system, the Kenyan climate envoy said there is need for a new system which is fair to all, adding that “Africa does not need favours, just fairness.”

Ali Mohammed, chair of the African group, speaking at an event on the sidelines of COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan. (Photo: UNFCCC)

What next for fossil fuel transition?

A year ago in Dubai, 196 countries agreed to “transition away from fossil fuels” in what became the first mention of fossil fuels in almost three decades of UN climate talks. Now, at COP29, delegates are having trouble deciding where to go next.

Observers told Climate Home it’s important to leave Baku with “strong signals” on the need to phase out oil and gas, but where and how it could happen remains unclear as the first week of COP draws to a close. Observers added that the several different options can make negotiations confusing.

One of the options is to discuss the energy transition under the UAE Dialogue, which is meant to discuss implementation of the main outcome from last year’s COP — the Global Stocktake.

But Like-Minded Developing Countries, a group that includes China, India and others, have opposed this for months and have pushed at COP29 for the dialogue to focus only on finance rather than fossil fuels. An informal note published yesterday still has both options – either limiting the scope of the dialogue to finance or also discussing the energy transition.

Adaptation Fund head laments “puzzling” lack of pledges at COP29

Meanwhile, the European Union and the UK have also pushed for countries to talk about fossil fuels as part of the mitigation work programme, which was set up at COP26 in Glasgow to enhance emissions reductions.

Three sources with access to behind-closed-door negotiations told Climate Home that Saudi Arabia and China have opposed fossil fuels being addressed in these talks, with some of them describing the Saudi position as “non-constructive”.

A draft text published yesterday proposes to use the same language as last year’s Global Stocktake. The draft also introduces new language on the phase out of fossil fuel subsidies – by defining them as “subsidies that do not address energy poverty or just transition”.

The chair of the African group Ali Mohamed told Climate Home that “there are attempts by other partners to impose new requirements which we are not comfortable with” in the mitigation work programme. He stressed the need to discuss finance.

Bronwen Tucker, a campaigner with Oil Change International, said that the mitigation work programme would be the best fit for an energy transition discussion, but added the current language does not increase ambition from last year’s pledge. “I definitely worry about being stuck in that loop for a long time,” she said.

Governments have struggled to include the COP28 fossil fuel pledge in other agreements this year. It was left out of a climate and biodiversity decision at last month’s COP16 in Cali and reports suggested it also struggled to make it into the G20 ministerial statement.

Speaking at a press conference, Fijian Deputy Prime Minister Biman Prasad said finance will be a “key element” for the fossil fuel transition, which is why the new climate finance goal (NCQG) – the main outcome of this COP – will also play a major role. The current NCQG draft does mention that climate finance should support the transition away from fossil fuels.

“We will advocate in every forum we can. That requires a robust, well-resourced and substantial finance goal here in Baku that has provisions to support all countries to exit fossil fuels,” Prasad said on the sidelines of COP29.

A protester against fossil fuels at COP29 (Flickr/UNFCCC/Habib Samadov)

GCF in line for funding boost

The main UN multilateral climate funds – the Green Climate Fund (GCF), Global Environment Facility (GEF) and Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD) – could be set for a funding boost from the COP29 finance talks.

The latest text on the New Collective Quantified Finance Goal (NCQG) – the main outcome of COP29 – says that governments decide to channel at least 20% of the public finance “provision element” of the goal through the main UN climate funds, described in technical jargon as the “operating entities of the financial mechanism of the Convention”.

That means the GCF, GEF and FRLD would all receive an eventual boost of funds. The text is outside of square brackets suggesting it has not so far been opposed.

The proposal stems from the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and is supported by small island developing states (SIDS) and the AILAC coalition of progressive Latin American countries.

Currently, less than 5% of climate finance passes through these operating entities – with the vast majority of the rest either government-to-government, through aid agencies like USAID, or via multilateral development banks (MDBs) like the World Bank. So 20% would be a much bigger slice of the pie.

Developing countries get more say over how climate finance is spent when it comes through the GCF because they have half of the board members. Voting power for MDBs depends on the stake each government has in the bank, which means bigger, richer nations have more power.

Bilateral climate finance is shaped by the donor government and its priorities for what it wants to spend its money on and where.

The GCF also distributes more of its money in grants than MDBs and its loans are at better rates, which avoids adding too much to developing countries’ debt burdens. But some developing countries have been critical of both the GCF and the GEF for their long list of requirements to access funds.

The GCF, GEF and FRLD all report back to the COP process and take instructions from the COP – unlike organisations like USAID and the World Bank.

Green Climate Fund executive director Mafalda Duarte at an event on the sidelines of COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan. (Photo: Green Climate Fund)

In brief…

The Trump effect: The upcoming change of government in the US, after the election of Donald Trump as president, could “delay” Colombia’s $40-billion plan for a just energy transition, as the country scouts for donors, environment minister Susana Muhamad told Climate Home News at COP29. Colombia is aiming to channel the funds for the plan through the Inter American Development Bank (IADB) and hopes “to leave it ready before we finish government”, she said.

COP31 stalemate: A meeting between the climate ministers of the two potential COP31 hosts, Turkiye and Australia, ended with neither backing down in their bid for the support of the “Western Europe and Others” regional group, whose turn it will be to organise the summit. After the meeting in Ankara, Turkiye’s environment minister Murat Kurum posted on X that he had “emphasised our country’s determination to host COP31”. A source with knowledge of negotiations told Climate Home a decision is now unlikely at COP29.

Dragged off over dogs: A video posted to social media purports to show Azeri animal rights activist Kamran Mammadli being violently detained in the COP29 Green Zone while protesting against the slaughter of stray dogs. While the Blue Zone is under United Nations control, the Green Zone is overseen by Azerbaijan’s authorities.

Billionaires tax at G20? Brazil has used its G20 presidency to push a global tax on billionaires to fund action against climate change, hunger and poverty. Brazil’s climate secretary Ana Toni told Climate Home today that Monday and Tuesday’s G20 leaders summit in Rio de Janeiro is likely to mention the tax. “Let us wait to see the leaders’ decision – to see how far they got it,” she said in Baku.

Economists’ “nonsense”: Climate Action Network International said today that Thursday’s UN-commissioned climate finance report by a group of economists was “nonsense” which “goes against the Paris Agreement” for saying that only 30% of the external climate finance needs of developing countries (except China) should be met through public finance. “The public finance is there by reining in fossil fuel subsidies, properly taxing the biggest polluters and wealthiest, and slimming down the extraordinary military budgets,” the environmental network of more than 1,800 NGOs said in a statement.