While adaptation funding jumped by about a quarter in 2022, a large share came as loans rather than grants, adding to developing-nations’ debt burdens

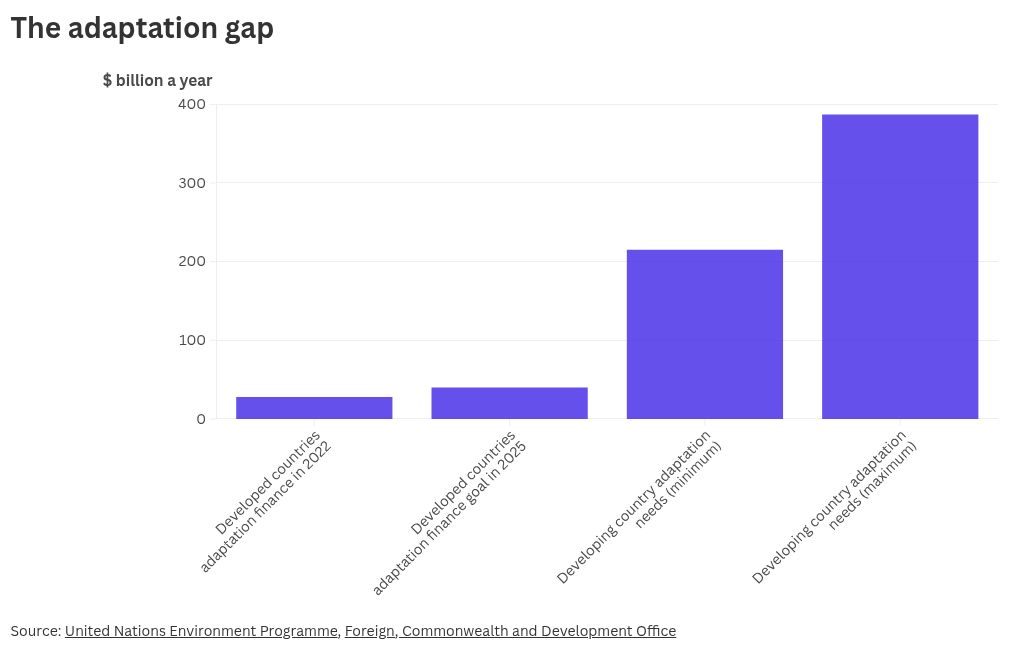

Rich countries have said they are on track to double their finance to help developing nations adapt to climate change by 2025 – but a new UN report shows that meeting this goal would cover just a tiny fraction of what poorer countries need to become more resilient to extreme weather and rising seas.

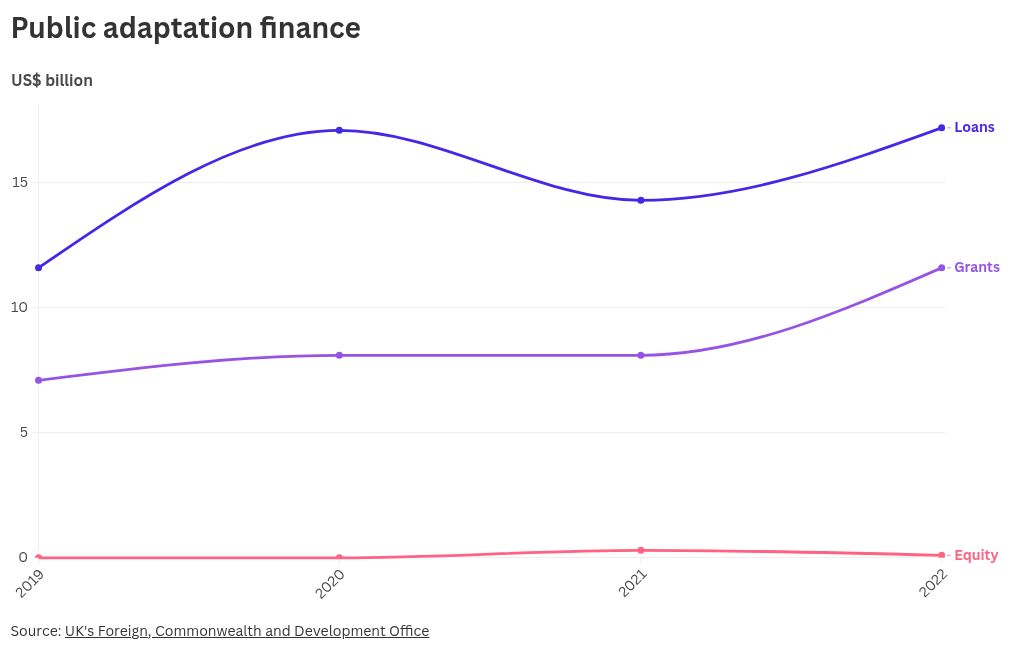

Adaptation finance provided by wealthy donors jumped by just over a quarter from $22 billion in 2021 to around $28 billion in 2022, led by an increase from multilateral development banks like the World Bank and the African and Asian Development Banks, the report showed.

Another report published on Monday by the UK’s foreign ministry, on behalf of developed countries, said the increase meant “efforts are on-track” for those countries to honour a promise they made at the COP26 climate summit in 2021 to double their finance from 2019 levels to around $40 billion by 2025.

But while United Nations Environment Programme Executive Director Inger Andersen called this an “encouraging sign” on Thursday, she added that “even achieving this goal would only reduce the adaptation finance gap by about 5%”.

The adaptation finance gap is the difference between the amount of money flowing towards adapting to climate change and the needs of developing countries. According to UNEP’s Adaptation Gap Report, published this week, those needs are estimated at $215 billion-$387 billion a year.

That compares with international public funding of over $28 billion in 2022, plus a further $3.5 billion mobilised from the private sector using public money to provide incentives. This leaves what UNEP describes as an “extremely large” gap.

Debt burden “injustice”

As well as quantity, developing countries and climate campaigners are concerned about the quality of adaptation finance. About three-fifths of the finance in 2022 came in the form of loans rather than grants, meaning it has to be paid back.

At the Adaptation Gap Report launch, Andersen said it is an “injustice that countries that have taken on debt to do activities in line with their development plan, get hit by catastrophic climate events and get put 20 years back”.

From cyclone to drought, Zimbabwe’s climate victims struggle to adapt

Mattias Söderberg, chief advisor at humanitarian NGO DanChurchAid, told Climate Home it was unfair to make developing countries that have contributed little to planet-heating emissions borrow money to adapt to it. He described it as like crashing someone’s car and then suggesting you’ll lend them the money to fix it.

“Adaptation is specifically needed in the poorest and most vulnerable countries, where debt is already a huge challenge,” Söderberg added.

Adaptation talks resume

At COP28 in Dubai last year, developing countries were disappointed that the talks did not set a new goal to provide finance and other forms of support for their adaptation efforts under wider negotiations on how to measure progress towards the “Global Goal on Adaptation”.

These discussions are likely to flare up again at COP29 in the next two weeks, where developing countries and climate justice campaigners are set to push for a clear target for adaptation funding as part of a new global climate finance goal due to be decided in Baku.

The African Group’s chief negotiator Ali Mohamed, from Kenya, told a recent webinar that adaptation would be his group’s “top priority”, as the continent’s low emissions and high climate vulnerability mean “adaptation is everything for us”.

(Reporting by Vivian Chime; editing by Joe Lo and Megan Rowling)