Developed countries could be sued for failing to provide sufficient climate finance, after the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled last week that, under the Paris Agreement, levels of public climate finance must be compatible with keeping global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

In their landmark advisory opinion delivered in The Hague, the ICJ’s 15 judges stated that, under the Paris pact, developed countries must provide financial support to help developing countries cut emissions “in a manner and at a level that allows for the achievement of” the agreement’s 1.5C warming limit.

Neither the judges nor the Paris Agreement specify exact amounts of finance required, but the judges said that the level “can be evaluated on the basis of several factors, including the capacity of developed States and the needs of developing States.”

The advisory opinion was issued last week, in response to a formal request from the United Nations General Assembly. The government of the Pacific island nation of Vanuatu was the major force behind it.

Held responsible on climate finance

Lawyer Margaretha Wewerinke-Singh represented Vanuatu in the case. Minutes after the opinion was read out, she told reporters on the steps of the ICJ’s courthouse that the judges had ruled governments have an obligation to provide enough climate finance. If they don’t, she said, the court had stated they should be held “responsible”.

She later told Climate Home it is difficult to determine exactly how much finance wealthy nations should be giving developing countries for climate finance but “it’s hard to see” how any less than the $1.3 trillion a year in government money that developed countries pushed for unsuccessfully at COP29 could be sufficient.

Wewerinke-Singh said ways to hold governments responsible would vary depending on each country’s legal system and its approach to international law. But, she added, at least in some nations, the ICJ opinion opens the door to lawsuits aiming to get courts to tell governments to revise their insufficient climate finance plans.

Ashfaq Khalfan, Oxfam America’s climate justice director, agreed. A “realistic best case scenario”, he said, is that domestic courts could question governments over how they have determined what their fair share of climate finance is in order to keep global warming to 1.5C – and instruct them to revise their plans if this has not been adequately considered.

But he added that courts were “very unlikely” to tell governments how much finance they should provide, as they consider writing budgets a matter for elected politicians not judges.

Domestic and European courts have already ordered governments, including the UK, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland, to revise what were judged to be inadequate plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But doing the same for finance would only be possible in countries where international law is treated as directly enforceable, Khalfan said. This includes France, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy and Spain – but not the US or the UK.

Climate lawyers look into it

Climate cases like this are usually brought by climate campaign groups, sometimes on behalf of or partnering with individual plaintiffs. Khalfan said he thought there would be many willing to bring legal action, although “it will depend whether philanthropy gets behind it as well” to fund the cost of the cases. Oxfam itself hasn’t pursued many legal cases but “would look into it”, he added.

A spokesperson for Friends of the Earth UK – which has taken the UK government to court over its emissions reduction and climate adaptation plans – said the group is “looking at the judgment very carefully to see how we can use it to strengthen our current and future climate casework”.

Lawsuits against developed countries could also be brought by other nations under the ICJ. These lawsuits have historically focused on disputes over international borders or natural resources but could now be brought over climate-driven destruction.

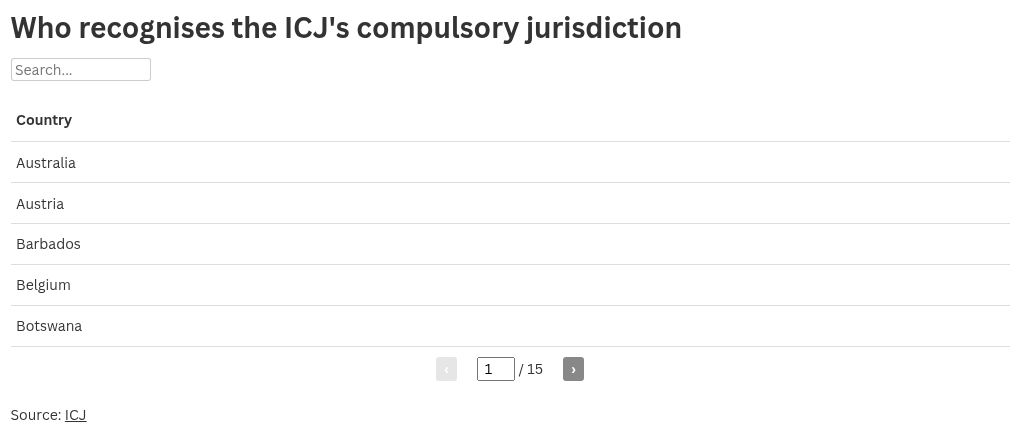

Khalfan said this would be “technically easier” than going through domestic courts. However, governments tend to have less respect for the ICJ than for their domestic courts, he added, and both the country suing and the country being sued would have to be among the 74 which have recognised the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ.

On top of this limitation, Khalfan said that “countries tend to be reluctant to sue each other unless they’re clear enemies” – like Russia and Ukraine, or Israel and South Africa. Wewerkinke-Singh agreed that domestic cases were likely to come ahead of international cases.

US still liable despite Paris exit

While some sections of the ICJ’s opinion only apply to signatories to the Paris Agreement – which the US will leave in January – Wewerinke-Singh said that other sections mean that the US still has an obligation to pay climate finance after it has left. Under unwritten “customary international law”, she interprets the opinion as saying all governments have duties to co-operate to prevent climate change.

Leaving the Paris Agreement makes it harder for the US to prove it is co-operating, she said, adding that “by ignoring these obligations they basically are digging their own grave almost” because it makes them liable to pay reparations. She said that, while the US does not recognise the ICJ’s jurisdiction, it can still be held accountable through the ICJ or through other enforcement mechanisms.

Which countries have not ratified the Paris climate agreement?

A government or group of governments can declare that another government has breached international law and – if that government doesn’t comply – then they can take counter measures, she explained. These could include economic sanctions or trade restrictions. But this would “require a bit of coalition-building between states”, she added.

Away from the legal arena, the opinion gives weight to diplomatic pushes to get wealthy nations to give more climate finance, an issue that dominated last year’s COP29 climate summit and will be raised again at COP30 in November.

The government of Vanuatu issued a statement saying it had “already started work to integrate the opinion into its climate-diplomacy toolbox” including by “urging developed partners to align bilateral and multilateral climate finance flows with the Court’s guidance”.

Development status is “not static”

The court also weighed in on the controversial issue of which governments are regarded as developed and which as developing under the UN climate regime. This affects which governments have to pay climate finance and which are eligible to receive it.

The current categorisation is based on lists drawn up when the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was signed in 1992. But since then, developed governments like the US or those in the European Union have argued that wealthier developing nations like South Korea, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and possibly China should pay climate finance.

The ICJ’s judges appeared to broadly back developed countries’ view, saying that the Paris Agreement’s mention of “different national circumstances” recognises that “the status of a State as developed or developing is not static. It depends on an assessment of the current circumstances of the State concerned.”

Joe Thwaites, a senior advocate for international climate finance at the US-based Natural Resources Defense Council, told Climate Home that this was “significant” and “could help unblock” UN climate talks “which often involve finger-pointing between developed countries and richer developing countries about who has the responsibility to provide climate finance”.

Oxfam America’s Khalfan said the ICJ was clear that “it is capacity rather than category that should apply here” and this would likely be used as an argument that high-income developing countries should pay – although he noted that China is still a middle-income country.

Vanuatu now plans to submit a resolution to the UN General Assembly asking governments to welcome and take forward the ICJ’s advisory opinion.