Wearing waders and work gloves, three dozen employees from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service stood at a small creek amid the dry sagebrush of southeastern Idaho. The group was eager to learn how to repair a stream the old-fashioned way.

Tipping back his white cowboy hat, 73-year-old rancher Jay Wilde told the group that he grew up swimming and fishing at this place, Birch Creek, all summer long. But when he took over the family farm from his parents in 1995, the stream was dry by mid-June.

Wilde realized this was partly because his family and neighbors, like generations of American settlers before them, had trapped and removed most of the dam-building beavers. The settlers also built roads, cut trees, mined streams, overgrazed livestock and created flood-control and irrigation structures, all of which changed the plumbing of watersheds like Birch Creek’s.

Many of the wetlands in the western United States have disappeared since the 1700s. California has lost an astonishing 90 percent of its wetlands, which includes streamsides, wet meadows and ponds. In Nevada, Idaho and Colorado, more than 50 percent of wetlands have vanished. Precious wet habitats now make up just 2 percent of the arid West — and those remaining wet places are struggling.

Nearly half of U.S. streams are in poor condition, unable to fully sustain wildlife and people, says Jeremy Maestas, a sagebrush ecosystem specialist with the NRCS who organized that workshop on Wilde’s ranch in 2016. As communities in the American West face increasing water shortages, more frequent and larger wildfires (SN: 9/26/20, p. 12) and unpredictable floods, restoring ailing waterways is becoming a necessity.

Staff from the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service pound posts to build a beaver dam analog across Birch Creek in Idaho in 2016. The effort gave nine relocated beavers a head start to create their own dam complexes.J. Maestas/USDA NRCS

Staff from the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service pound posts to build a beaver dam analog across Birch Creek in Idaho in 2016. The effort gave nine relocated beavers a head start to create their own dam complexes.J. Maestas/USDA NRCS

Landowners and conservation groups are bringing in teams of volunteers and workers, like the NRCS group, to build low-cost solutions from sticks and stones. And the work is making a difference. Streams are running longer into the summer, beavers and other animals are returning, and a study last December confirmed that landscapes irrigated by beaver activity can resist wildfires.

Filling the sponge

Think of a floodplain as a sponge: Each spring, floodplains in the West soak up snow melting from the mountains. The sponge is then wrung out during summer and fall, when the snow is gone and rainfall is scarce. The more water that stays in the sponge, the longer streams can flow and plants can thrive. A full sponge makes the landscape better equipped to handle natural disasters, since wet places full of green vegetation can slow floods, tolerate droughts or stall flames.

Typical modern-day stream and river restoration methods can cost about $500,000 per mile, says Joseph Wheaton, a geomorphologist at Utah State University in Logan. Projects are often complex, and involve excavators and bulldozers to shore up streambanks using giant boulders or to construct brand-new channels.

“Even though we spend at least $15 billion per year repairing waterways in the U.S., we’re hardly scratching the surface of what needs fixing,” Wheaton says.

Big yellow machines are certainly necessary for restoring big rivers. But 90 percent of all U.S. waterways are small streams, the kind you can hop over or wade across.

For smaller streams, hand-built restoration solutions work well, often at one-tenth the cost, Wheaton says, and can be self-sustaining once nature takes over. These low-tech approaches include building beaver dam analogs to entice beavers to stay and get to work, erecting small rock dams or strategically mounding mud and branches in a stream. The goal of these simple structures is to slow the flow of water and spread it across the floodplain to help plants grow and to fill the underground sponge.

Less than a year after workers installed this hand-built rock structure, called a Zuni bowl, in an intermittent stream in southwestern Montana, erosion stopped moving upstream, keeping the grass above the structure green and lush.Sean Claffey/Southwest Montana Sagebrush Partnership

Less than a year after workers installed this hand-built rock structure, called a Zuni bowl, in an intermittent stream in southwestern Montana, erosion stopped moving upstream, keeping the grass above the structure green and lush.Sean Claffey/Southwest Montana Sagebrush Partnership

Fixes like these help cure a common ailment that afflicts most streams out West, including Birch Creek, Wheaton says: Human activities have altered these waterways into straightened channels largely devoid of debris. As a result, most riverscapes flow too straight and too fast.

“They should be messy and inefficient,” he says. “They need more structure, whether it’s wood, rock, roots or dirt. That’s what slows down the water.” Wheaton prefers the term “riverscape” over stream or river because he “can’t imagine a healthy river without including the land around it.”

Natural structures “feed the stream a healthy diet” of natural materials, allowing soil and water to accumulate again in the floodplain, he says.

Since as much as 75 percent of water resources in the West are on private land, conservation groups and government agencies like the NRCS are helping ranchers and farmers improve the streams, springs or wet meadows on their property.

“In the West, water is life,” Maestas says. “But it’s a very time-limited resource. We’re trying to keep what we have on the landscape as long as possible.”

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Beaver benefits

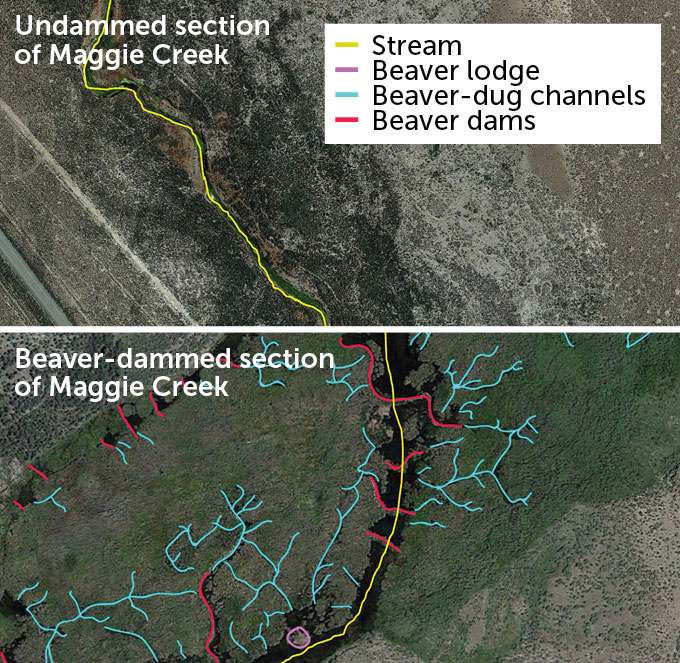

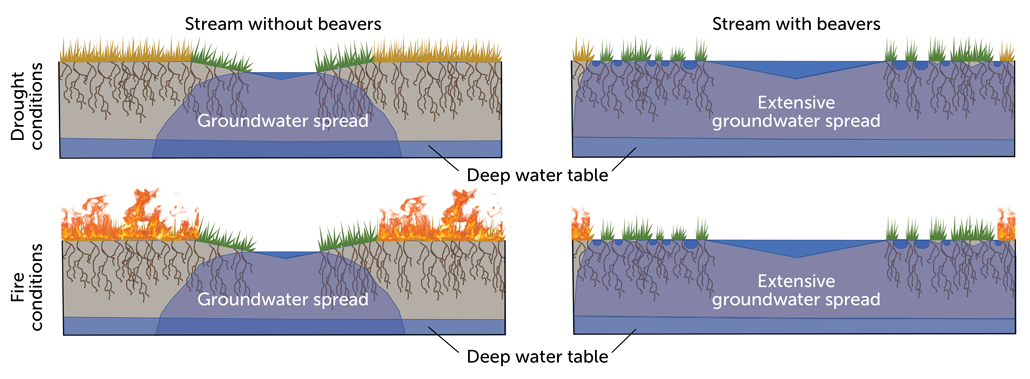

In watersheds across the West, beavers can be a big part of filling the floodplain’s sponge. The rodents gnaw down trees to create lodges and dams, and dig channels for transporting their logs to the dams. All this work slows down and spreads out the water.

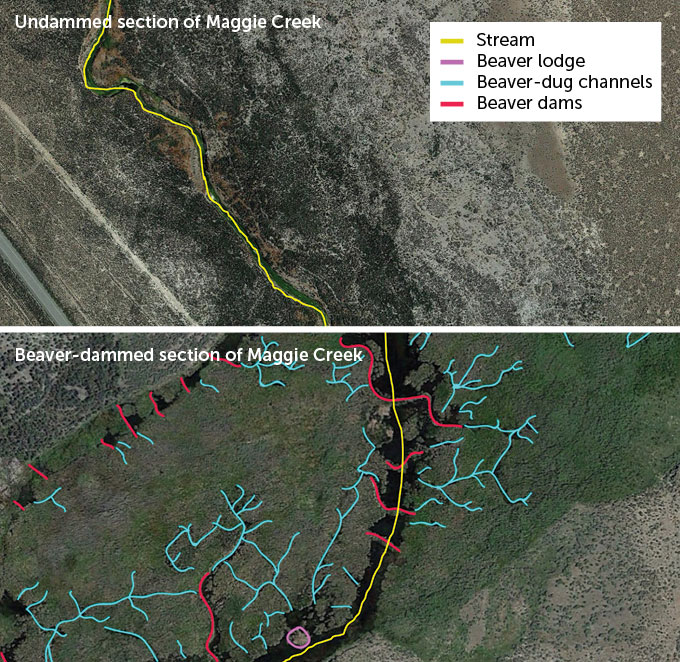

On two creeks in northeastern Nevada, streamsides near beaver dams were up to 88 percent greener than undammed stream sections when measured from 2013 to 2016. Even better, beaver ponds helped maintain lush vegetation during the hottest summer months, even during a multiyear drought, Emily Fairfax, an ecohydrologist at California State University Channel Islands, and geologist Eric Small of University of Colorado Boulder reported in 2018 in Ecohydrology.

Satellite images show that when beavers settled into one part of Nevada’s Maggie Creek (bottom), digging channels to ferry in logs to build dams, the floodplain was wider, wetter and greener than an area of the creek with no dams (top).E. Fairfax/CSU Channel Islands

Satellite images show that when beavers settled into one part of Nevada’s Maggie Creek (bottom), digging channels to ferry in logs to build dams, the floodplain was wider, wetter and greener than an area of the creek with no dams (top).E. Fairfax/CSU Channel Islands  Satellite images show that when beavers settled into one part of Nevada’s Maggie Creek (bottom), digging channels to ferry in logs to build dams, the floodplain was wider, wetter and greener than an area of the creek with no dams (top).E. Fairfax/CSU Channel Islands

Satellite images show that when beavers settled into one part of Nevada’s Maggie Creek (bottom), digging channels to ferry in logs to build dams, the floodplain was wider, wetter and greener than an area of the creek with no dams (top).E. Fairfax/CSU Channel Islands

“Bringing beavers back just makes good common sense when you get down to the science of it,” Wilde says. He did it on his ranch.

Using beavers to restore watersheds is not a new idea. In 1948, for instance, Idaho Fish and Game biologists parachuted beavers out of airplanes, partly to improve trout habitat on public lands.

Wilde used trucks instead of parachutes. In 2015 and 2016, he partnered with the U.S. Forest Service and Idaho Fish and Game to livetrap and relocate nine beavers to Birch Creek from public lands about 120 kilometers away. To ensure the released rodents had a few initial ponds where they could escape from predators, Wilde worked with Anabranch Solutions, a riverscape restoration company cofounded by Wheaton and colleagues, to construct 26 beaver dam analogs. Would these simple branch-and-post structures entice the beavers to stay in Birch Creek?

It worked like a charm. In just three years, those beavers built 149 dams, transforming the once-narrow strip of green along the stream into a wide, vibrant floodplain. Birch Creek flowed 42 days longer, through the hottest part of the summer. Fish rebounded quickly too: Native Bonneville cutthroat trout populations were up to 50 times as abundant in the ponded sections in 2019 as they were when surveyed by the U.S. Forest Service in 2000, before beavers went to work.

“When you see the results, it’s almost like magic,” Wilde says. Even more magical, the transformation cost Wilde only “a couple hundred bucks in fence posts” and a few days of sweat equity, thanks in part to those NRCS staffers who came in 2016 and a host of volunteers.

The water is wide

When beavers build dams, water spreads out to the surrounding vegetation. Pockets of water under the streamside plants support the plants during drought, which then repel fires much better than dry vegetation.

How beavers help in drought and fire  E. Fairfax/CSU Channel Islands

E. Fairfax/CSU Channel Islands  E. Fairfax/CSU Channel Islands

E. Fairfax/CSU Channel Islands

Rock dams in the desert

Beaver-powered restoration isn’t the answer everywhere, especially in the desert where creeks are ephemeral, flowing only intermittently. In Colorado’s Gunnison River basin, ranchers were looking for ways to boost water availability to ensure their cattle had enough drinking water and green grass in the face of climate change. Meanwhile, the area’s public land managers wanted to restore streams to help at-risk wildlife species like the Gunnison sage grouse, once prolific across sagebrush country.

In 2012, a group of private landowners, public agencies and nonprofit organizations launched the Gunnison Basin Wet Meadow and Riparian Restoration and Resilience-building Project to revive streams and keep meadows green. The group hired Bill Zeedyk to instruct on how to build simple, low-profile dams by stacking rocks, known widely as Zeedyk structures, to slow down the water.

Zeedyk, now 85, runs his own wetland and stream restoration firm in New Mexico, after 34 years as a wildlife biologist at the U.S. Forest Service. His 2014 book Let the Water Do the Work has inspired people across the West — including Maestas and Wheaton — to turn to simple, nature-based stream restoration solutions.

Over the last nine years, Zeedyk has helped the Gunnison collaborative build nearly 2,000 rock structures throughout the roughly 10,000-square-kilometer upper Gunnison watershed. The group has restored 43 kilometers of stream and improved nearly 500 hectares of wet habitat for people and wildlife. A typical project involves a dozen volunteers working for a day or two in one creek bottom where they build dozens of rock structures.

In 2017, Maestas asked Zeedyk to show more than 100 people involved in the NRCS-led Sage Grouse Initiative how to install rock structures. The white-bearded Zeedyk led them along an eroding gully near Gunnison that June.

Conservation professionals gathered in Gunnison, Colo., in 2017 to learn how to build Zeedyk structures, simple rock dams that slow the flow of water in small creeks to increase surrounding plant growth.B. Randall

Conservation professionals gathered in Gunnison, Colo., in 2017 to learn how to build Zeedyk structures, simple rock dams that slow the flow of water in small creeks to increase surrounding plant growth.B. Randall

Lifting his wooden walking staff, Zeedyk pointed out how the adjacent dirt road originally created by horses and wagons cut off the creek from its historic floodplain. The road made the channel shorter, straighter and steeper over time. “There’s less growing space, and the whole system is less productive,” he explained.

As participants decided where to stack rocks to spread water across the dusty sagebrush flat, Zeedyk encouraged them to “read the landscape” and “think like water.” After three hours of work, participants could already see ponds forming behind their rock creations.

Watching the teams work and laugh together, Maestas called it the aha moment for the crew. “When you get your hands dirty, there’s a degree of buy-in that can’t come from sitting in a classroom or reading about it.”

The grass is greener

The hope is that, like the beaver dam analogs, these hand-built rock structures will halt erosion, capture sediment, fill the floodplain sponge and grow more water-loving plants.

Patience, Zeedyk says, is crucial. “After we put natural processes into play in a positive direction, we have to wait for the water to do its work.”

The wait isn’t necessarily long. At four of the sites in the Gunnison basin restored with Zeedyk structures, wetland plant cover (including sedges, rushes, willows and wetland forbs) increased an average of 160 percent four years post-treatment, compared with a 15 percent average increase at untreated areas near each study site, according to a 2017 report by The Nature Conservancy.

“As of 2019, we had increased the wetland species cover by 200 percent in six years,” says Renee Rondeau, an ecologist at the Colorado Natural Heritage Program, based in Hesperus. “So great to see this success.”

Animals seem to enjoy all that fresh green growth too. Colorado Parks and Wildlife set up remote cameras to monitor whether wildlife use the restored floodplain. Since 2016, the cameras have captured more than 1.5 million images, most of which show a host of animals — from cattle and elk to sage grouse and voles — munching away in the now-lush meadows. A graduate student at Western Colorado University is classifying photos to determine whether there’s a significant difference in the number of Gunnison sage grouse at the restored sites compared with adjacent untreated areas.

“Sage grouse chicks chase the green line as the desert dries up,” Maestas explains. After hatching in June, hens and their broods seek out wet areas where chicks stock up on protein-rich insects and wildflowers to grow and survive the winter.

A remote camera spies Gunnison sage grouse feasting on insects and plants in a wet meadow. The area stays green long into the summer because of hand-built rock dams that spread water across the land.Courtesy of Nathan Seward/Colorado Parks and Wildlife

A remote camera spies Gunnison sage grouse feasting on insects and plants in a wet meadow. The area stays green long into the summer because of hand-built rock dams that spread water across the land.Courtesy of Nathan Seward/Colorado Parks and Wildlife

Water in the bank

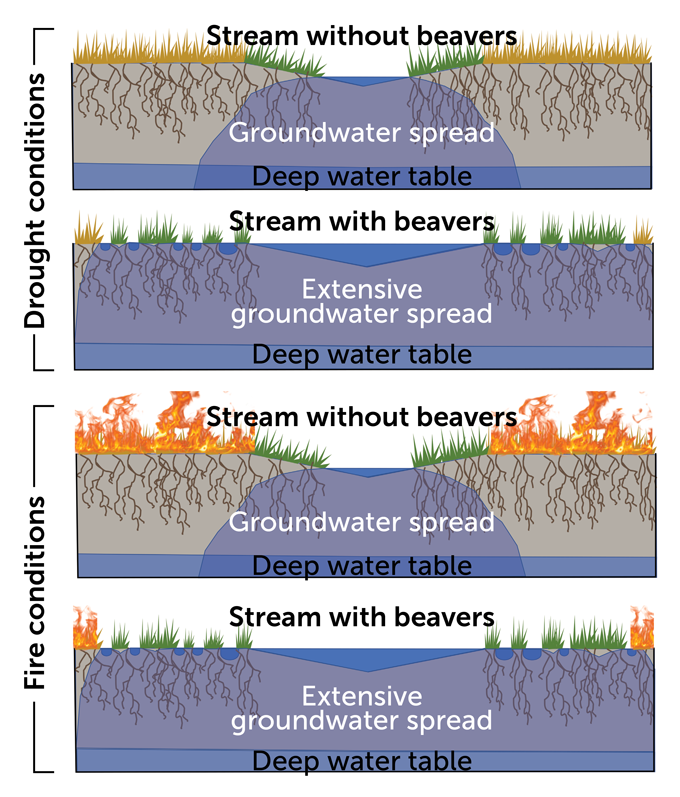

The Gunnison basin is not the only place where sticks-and-stones restoration is paying dividends for people and wildlife. Nick Silverman, a hydroclimatologist and geospatial data scientist, and his colleagues at the University of Montana in Missoula used satellite imagery to evaluate changes in “greenness” at three sites that used different simple stream restoration treatments: Zeedyk’s rock structures in Gunnison, beaver dam analogs in Oregon’s Bridge Creek and fencing projects that kept livestock away from streambanks in northeastern Nevada’s Maggie Creek.

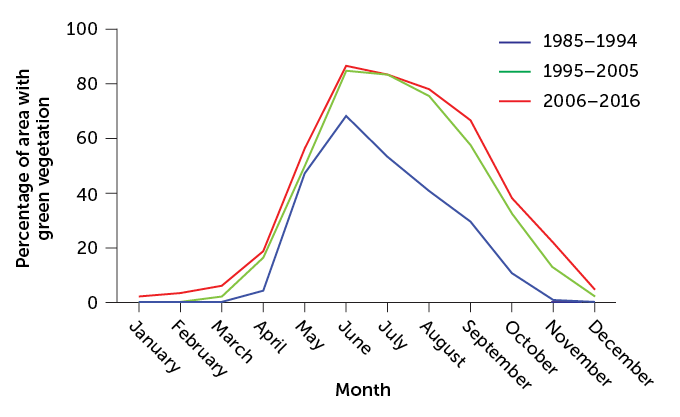

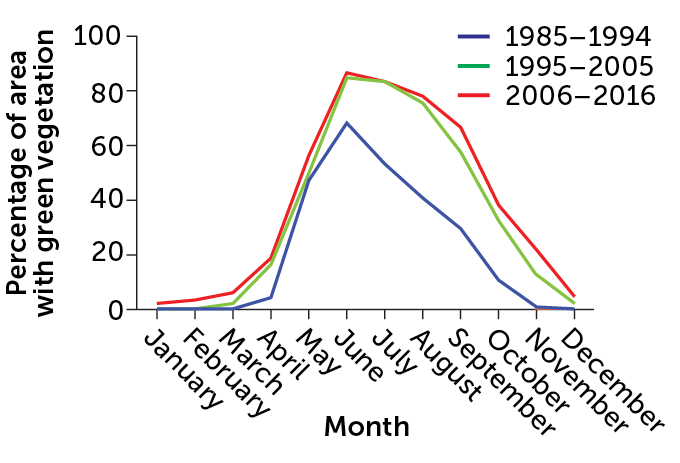

Late summer greenness increased up to 25 percent after streams were restored compared with before, the researchers reported in 2018 in Restoration Ecology. Plus, the streams showed greater resilience to climate variability as time went on: Along Maggie Creek, restored more than two decades before the study, the plants stayed green even when rainfall was low, and the area had substantial increases in plant production during late summer, when vegetation usually dries out.

Lasting change

In 1994, ranchers in Nevada began changing livestock grazing practices at Maggie Creek to encourage vegetation to regrow along the stream and support new beaver colonies. The graph compares average monthly greenness pre-restoration (blue) and post. In the first (green) and second decade (red) after, vegetation lasted longer into fall and winter months.

Effect of restoration at Maggie Creek, Nevada  C. Chang

C. Chang  C. Chang Source: N.L. Silverman et al/Restoration Ecology 2019

C. Chang Source: N.L. Silverman et al/Restoration Ecology 2019

“It’s like putting water in a piggy bank when it’s wet, so plants and animals can withdraw it later when it’s dry,” Silverman says. Even more exciting, he adds, is that the impact of the low-cost options is large enough to see from space.

Water doesn’t burn

The Sharps Fire that scorched south-central Idaho in July 2018 burned a wide swath of a watershed where Idaho Fish and Game had relocated beavers to restore a floodplain. A strip of wet, green vegetation stood untouched along the beavers’ ponds. Wheaton sent a drone to take photos, tweeting out an image on September 5, 2018: “Why is there an impressive patch of green in the middle of 65,000 acres of charcoal? Turns out water doesn’t burn. Thank you beaver!”

The green strip of vegetation along beaver-made ponds in Baugh Creek near Hailey, Idaho, resisted flames when a wildfire scorched the region in 2018, as shown in this drone image.J. Wheaton/Utah State Univ.

The green strip of vegetation along beaver-made ponds in Baugh Creek near Hailey, Idaho, resisted flames when a wildfire scorched the region in 2018, as shown in this drone image.J. Wheaton/Utah State Univ.

Fairfax, the ecohydrologist who reported that beaver dams increase streamside greenness, had been searching for evidence that beavers could help keep flames at bay. Wheaton’s tweet was a “kick in the pants to push my own research on beavers and fire forward,” she says.

With undergraduate student Andrew Whittle, now at the Colorado School of Mines, Fairfax got to work analyzing satellite imagery from recent wildfires. The two mapped thousands of beaver dams within wildfire-burned areas in several western states. Choosing five fires of varying severity in both shrubland and forested areas, the pair analyzed the data to see if creeks with beaver activity stayed greener than creeks without beavers during wildfires.

Emily Fairfax produced this stop-motion video to show how beavers and their dams and channels keep water in an area, supporting the surrounding vegetation and helping the area resist wildfires.

“Across the board, beaver-dammed areas didn’t burn,” Fairfax says. The study was published last December in Ecological Applications during one of the West’s worst fire seasons. It garnered plenty of attention from land managers asking for more specifics, like how many beavers are needed to buffer a fire.

Fairfax plans to study several more burned sites with beaver ponds. She hopes to eventually create a statistical model that can help people plan nature-powered stream restoration projects.

“When we’re seeing hotter, more unpredictable fires that are breaking all the rules we know of,” Fairfax says, “we have to figure out how to preserve critical wet habitats.”