An international team of astronomers is the first to apply an old technique to discover a new type of planet that orbits two stars – what is known as a circumbinary planet. It is only the second such system found with 2 planets.

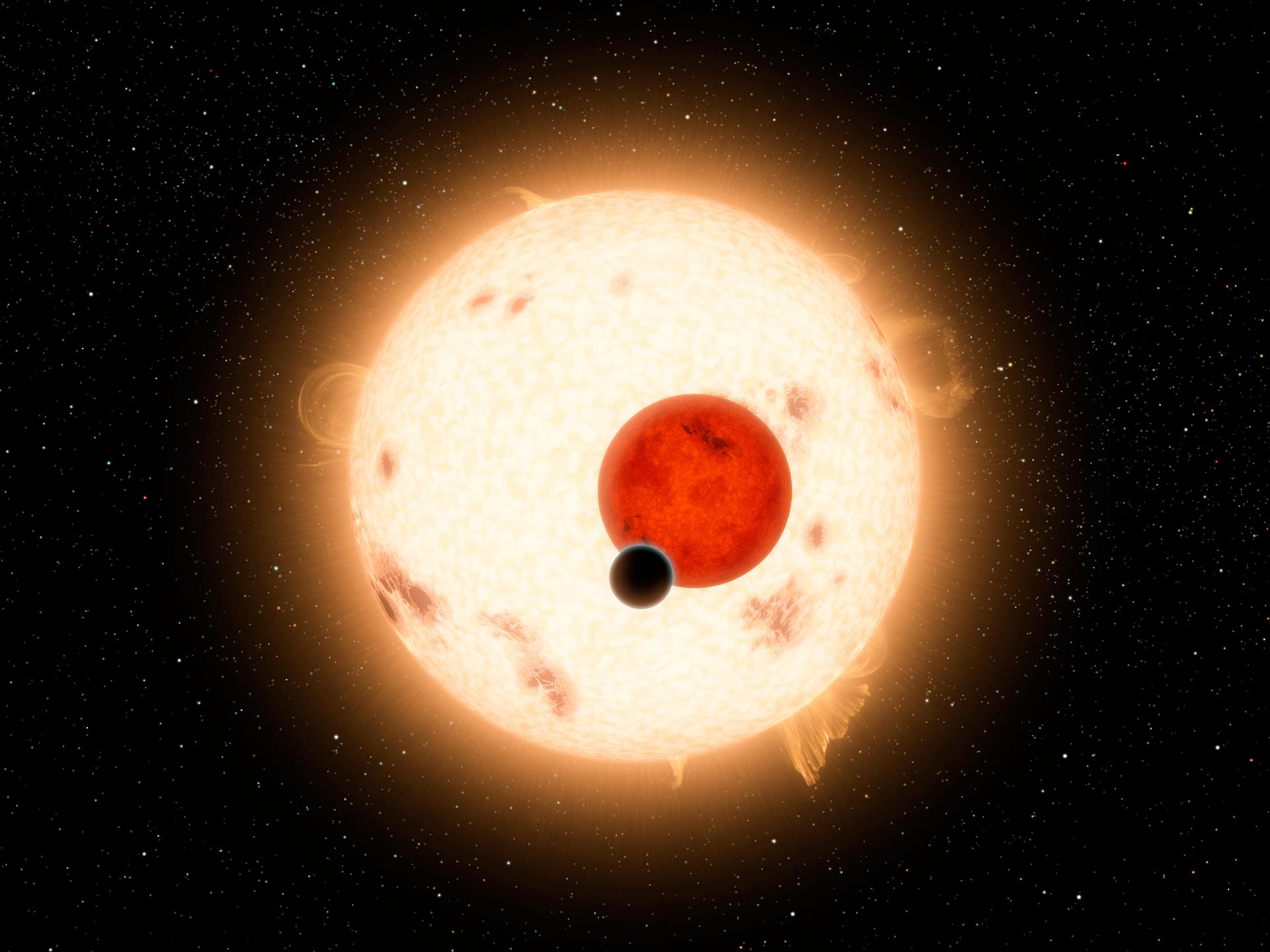

A binary star – illustrative artistic visualization. Image credit: NASA/C. Reed

As an added bonus, researchers found a second planet that is orbiting the same two stars, which is only the second confirmed multi-planet circumbinary system found to date. The study was published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Circumbinary planets were once relegated to only science fiction, but thanks to data collected from NASA’s Kepler mission, astronomers now know that multiple star systems are more common than previously thought.

While many may not have planets of their own, roughly half the stars in the sky are made up of double, triple or quaternary formations. The other half are single stars like our sun, yet despite their quantity, scientists understand very little about the planets that form around multiple star systems.

“When a planet orbits two stars, it can be a bit more complicated to find because both of its stars are also moving through space,” said David Martin, co-author of the study and NASA Sagan Fellow in astronomy at The Ohio State University. “So how we can detect these stars’ exoplanets, and how they are formed, are all quite different.”

The newly discovered system is called TOI-1338/BEBOP-1 for the planetary detection survey Binaries Escorted by Orbiting Planets, the team initiated to increase the number of known circumbinary planets. It is only the second binary star system known to host multiple planets ever confirmed. Only 12 circumbinary planet systems have ever been discovered.

Years before science discovered planets orbiting two stars, Star Wars showed Luke Skywalker facing a twin sunset on his home world Tatooine. Image credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

At the heart of their finding, the study revealed a large gas giant with an orbital period around the two stars of 215 days.

But what makes their discovery so special, Martin said, is how the planet was located. Of the more than 5,000 worlds that astronomers have found since the first exoplanet was discovered in 1995, most have been tracked down using a technique called the transit method.

Widely considered to be the most effective way of proving the existence of other worlds, the method allows astronomers to indirectly detect a planet by measuring a dip in the brightness of light when a planet crosses between a star and an observer on Earth.

However, in this study, researchers detail the first-ever detection of a known circumbinary planet solely using observations made with the radial velocities method, an approach that relies on measuring the gravitational shifts planets exert on their host stars over time. It’s the same approach used to find the 1995 exoplanet, now known as Dimidium.

“Whereas people were previously able to find planets around single stars using radial velocities pretty easily, this technique was not being successfully used to search for binaries,” said Martin.

It’s because radial velocities, while successful at detecting planets around single stars, have historically struggled to find planets in binaries where there are multiple sets of stellar spectra, he said. Yet by targeting binaries where one star is much brighter than the other, the BEBOP program could soon help find many more, said Martin.

Previous research has shown that radial velocities could be used to locate a planetary system astronomers were already aware of called Kepler-16, but this study advances that work by discovering a brand new planet.

The discovery could also bode well for scientists devoted to looking for life on other planets, as according to the study, the inner planet already found in this binary system would be a prime candidate for atmospheric study by the James Webb Space Telescope.

Atmospheric characterizations search for proof of biological activity and assess the likelihood of a planet having conditions conducive to life as humans on Earth know it.

If NASA does choose to turn Webb’s eye toward the planet in this study, it would be the first system of its kind amenable to atmospheric investigation, Martin said. “If we are to unveil the mysteries and intricacies behind circumbinary planets, our discovery provides a new hope,” he said.

Source: Ohio State University