When Igor de Almeida moved to Japan from Brazil nine years ago, the transition should have been relatively easy. Both Japan and Brazil are collectivist nations, where people tend to value the group’s needs over their own. And research shows that immigrants adapt more easily when the home and new country’s cultures match.

But to de Almeida, a cultural psychologist now at Kyoto University, the countries’ cultural differences were striking. Japanese people prioritize formal relationships, such as with coworkers or members of the same “bukatsu,” or extracurricular club, for instance, while Brazilian people prioritize friends in their informal social network. “Sometimes I try to find [cultural] similarities but it’s really hard,” de Almeida says.

Now, new research helps explain that disconnect. For decades, psychologists have studied how culture shapes the mind, or people’s thoughts and behaviors, by comparing Eastern and Western nations. But two research groups working independently in Latin America are finding that a cultural framework that splits the world in two is overly simplistic, obscuring nuances elsewhere in the world.

Due to differences in methodology and interpretation, the teams’ findings about how people living in the collectivist nations of Latin America think are also contradictory. And that raises a larger question: Will overarching cultural theories based on East-West divisions hold up over time, or are new theories needed?

However this debate unfolds, cultural psychologists argue that the field must expand. “If you make most of the cultures of the world … invisible,” says Vivian Vignoles, a cultural psychologist at the University of Sussex in England, “you will get all sorts of things wrong.”

Such misconceptions can jeopardize political alliances, business relationships, public health initiatives and general theories for how people find happiness and meaning. “Culture shapes what it means to be a person,” says Stanford University behavioral scientist Hazel Rose Markus. “What it means to be a person guides all of our behavior, how we think, how we feel, what motivates us [and] how we respond to other individuals and groups.”

More than 200,000 Brazilians live in Japan today. But even though Brazil and Japan share a collectivist cultural framework, researchers are finding that the people think and behave in markedly different ways, making assimilation difficult. Here, Brazilian Japanese people play on traditional Japanese “taiko” drums.Paulo Guereta/Wikimedia Commmons (CC BY 2.0)

More than 200,000 Brazilians live in Japan today. But even though Brazil and Japan share a collectivist cultural framework, researchers are finding that the people think and behave in markedly different ways, making assimilation difficult. Here, Brazilian Japanese people play on traditional Japanese “taiko” drums.Paulo Guereta/Wikimedia Commmons (CC BY 2.0)

Culture and the mind

Until four decades ago, most psychologists believed that culture had little bearing on the mind. That changed in 1980. Surveys of IBM employees taken across some 70 countries showed that attitudes toward work largely depended on workers’ home country, IBM organizational psychologist Geert Hofstede’s wrote in Culture’s Consequences.

Markus and Shinobu Kitayama, a cultural psychologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, subsequently fleshed out one Hofstede’s four cultural principles: Individualism versus collectivism. Culture does influence thinking, the duo claimed in a now widely cited paper in the 1991 Psychological Review. By comparing people in mostly the East and West, they surmised that living in individualist countries (i.e. Western ones) led people to think independently while living in collectivist countries (the East) led people to think interdependently.

That paper was pioneering at the time, Vignoles says. Before that, with psychological research based almost exclusively in the West, the Western mind had become the default mind. Now, “instead of being only one kind of person in the world, there [were] two kinds of persons in the world.”

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Latin America: A case study

How individualism/collectivism shape the mind now undergirds the field of cross-cultural psychology. But researchers continue to treat the East and West, chiefly Japan and the United States, as prototypes, Vignoles and colleagues say.

To expand beyond that narrow lens, the team surveyed 7,279 participants in 33 nations and 55 cultures. Participants read such statements as “I prefer to turn to other people for help rather than solely rely on myself” and “I consider my happiness separate from the happiness of my friends and family.” They then responded to how well those comments reflected their values on a scale from 1 for “not at all” to 9 for “exactly.”

That analysis allowed the researchers to identify seven dimensions of independence/interdependence, including self-reliance versus dependence on others and emphasis on self-expression versus harmony. Strikingly, Latin Americans were as, or more, independent as Westerners in six out of the seven dimensions, the team reported in 2016 in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

The researchers’ subsequent analysis of four studies comprising 17,255 participants across 53 nations largely reaffirmed that surprising finding. For instance, Latin Americans are more expressive than even Westerners, Vignoles, de Almeida and colleagues report in February in Perspectives in Psychological Science. But that finding violates the common view that people living in collectivist societies suppress their emotions to foster harmony, while people in individualistic countries emote as a form of self-expression.

More mentions for East and West

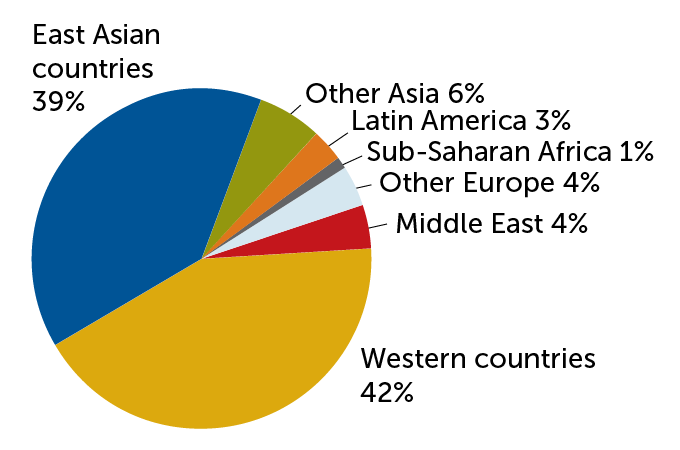

Researchers identified 558 articles investigating thinking patterns or “self-construals.” The team counted countries mentioned in the articles’ titles and abstracts. Western countries, such as the United States and Germany, received 42 percent of all mentions while East Asian countries, such as China and Japan, received 39 percent. Latin American countries, such as Brazil and Mexico, received 1/15th the mentions that East Asian countries did.

Percentage of articles mentioning East, West or the rest C. ChangC. Chang Source: K. Krys et al/Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2022

C. ChangC. Chang Source: K. Krys et al/Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2022

Latin American nations are collectivist, as defined by Hofstede and others, but the people think and behave independently, the team concludes.

Kitayama’s team has a different take: Latin Americans are interdependent, just in a wholly different way than East Asians. Rather than suppressing emotions, Latin Americans tend to express positive, socially engaging emotions to communicate with others, says cultural psychologist Cristina Salvador of Duke University. That fosters interdependence, unlike the way Westerners express emotions to show their personal feelings. Westerners’ feelings can be negative or positive and often have little to do with their social surroundings — a sign of independence.

Salvador, Kitayama and colleagues had more than 1,000 respondents in Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Japan and the United States reflect on various social scenarios, instead of asking explicit questions like Vignoles’ team. For instance, respondents were asked to imagine winning a prize. They then picked what emotions — such as shame, guilt, anger, friendliness or closeness to others — they would express with family and friends.

Respondents from Latin America and the United States both expressed strong emotions, Salvador reported in February at the Society for Personality and Social Psychology conference in San Francisco. But people in the United States expressed egocentric emotions, such as pride, while people in Latin America expressed emotions that emphasize connection with others.

Because Latin America’s high ethnic and linguistic diversity made communication with words difficult, people learned how to communicate in other ways, Kitayama says. “Emotion became a very important means of social communication.”

Decentering the West

More research is needed to reconcile those findings. But how should that research proceed? Though a shift to a broader framework has begun, research in cultural psychology still hinges on the East-West binary, researchers from both teams say.

Psychologists who peer review studies for acceptance into scientific journals still “want a mainstream, white, U.S. comparison sample,” Salvador says. “[Often] you need an Asian sample, as well.”

The primacy of the East and West means that psychological differences between those two regions dominate research and discussions. But both teams are expanding the scope of their research despite those challenges.

Kitayama’s team, for instance, maps out how interdependence, which it argues precedes the emergence of independence, might have morphed as it spread around the globe, in a theory paper also presented at the San Francisco conference (SN: 11/7/19). Besides diversity giving way to “expressive interdependence” in Latin America, the team describes “self-effacing interdependence in East Asia” stemming from the communal nature of rice farming, “self-assertive interdependence” in Arab regions arising from the nomadic life and “argumentative interdependence” in South Asia arising from its central role in trade (SN: 7/14/14).

The nature of interdependent thinking varies by world region, theorizes one group of cultural psychologists. “Self-effacing interdependence” arose in East Asian communities due the cooperative nature of rice farming while self-assertive independence” arose in Arab regions, such as this community in Iran, due to the more solitary nomadic life.Hamed Saber/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

The nature of interdependent thinking varies by world region, theorizes one group of cultural psychologists. “Self-effacing interdependence” arose in East Asian communities due the cooperative nature of rice farming while self-assertive independence” arose in Arab regions, such as this community in Iran, due to the more solitary nomadic life.Hamed Saber/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

This research started with a “West and the rest” mentality, Kitayama says. His work with Markus created an “East-West and the rest” mentality. Now finally, psychologists are grappling with “the rest,” he says. “The time is really ready to expand this [research] to cover the rest of the world.”

De Almeida imagines decentering the West yet further. What if researchers had started off by comparing Japan and Brazil instead of Japan and the United States, he wonders. Instead of the current laser focus on individualism/collectivism, some other defining facet of culture would have likely risen to prominence. “I would say emotional expression, that’s the most important thing,” de Almeida says.

He sees a straightforward solution. “We could increase the number of studies not involving the United States,” he says. “Then we could develop new paradigms.”