Probiotics are classified as dietary supplements, and as such, ARE NOT regulated by the FDA, and do not need data to demonstrate effectiveness, safety, or quality before they are sold. (read more about the regulation of dietary supplements here)

The number of adults in the U.S. taking probiotics or their cousins, prebiotics (typically nondigestible fibers that favor the development of gut bacteria), more than quadrupled between 2007 and 2012, from 865,000 people to nearly four million. The global probiotic market was valued at $77 BILLION in 2022 and is projected to grow 14% YoY. Yes, it is very much a lucrative industry that is wholly unregulated.

Probiotic supplements are live microorganisms

These supplements typically contain one or a small handful of live bacteria and/or yeasts that may be found in your body. In the case of probiotics, these are typically species that are views as benign or beneficial, as they are found as part of your microbiome.

Probiotics are part of a larger picture regarding bacteria and your body — your microbiome.

The microbiome is described as a diverse community of organisms that work together to keep your body healthy. This community is made up of things called microbes. You have trillions of microbes on and in your body. These microbes are a combination of:

- Bacteria.

- Fungi (including yeasts).

- Viruses.

- Protozoa.

Probiotic supplements have gained popularity in recent years as microbiology researchers have begun to understand the implications of our microbiome, particularly gut microbiome, for human health.

Increasing evidence has associated changes in gut microbiota to both gastrointestinal and extra-gastrointestinal diseases. Unfortunately, the fact that we are beginning to tease apart the complexity of the microbiome means that wellness companies have capitalized on this and are utilizing this to market products. Enter: probiotics.

The complexity and importance of the microbiome is exploited to sell unproven supplements

These supplement companies claim to be able to augment our normal microbiome in order to cure or resolve a variety of ailments. And since we 1) understand the fact that the microbiome is involved in a variety of cellular processes and 2) we don’t fully understand how these interactions work means that they can use just enough buzzwords to prey on the consumers.

The majority of studies to date have failed to reveal any benefits in individuals who are already healthy. There is no evidence to suggest that people with normal gastrointestinal tracts can benefit from taking probiotics.

One thing that’s important to remember is that everyone’s microbiome is unique. No two people have the same microbial cells — even twins are different.

The gut microbiome consists of TRILLIONS of different microorganisms

The human gastrointestinal system contains about 39 trillion bacteria, according to the latest estimate, most of which reside in the large intestine.

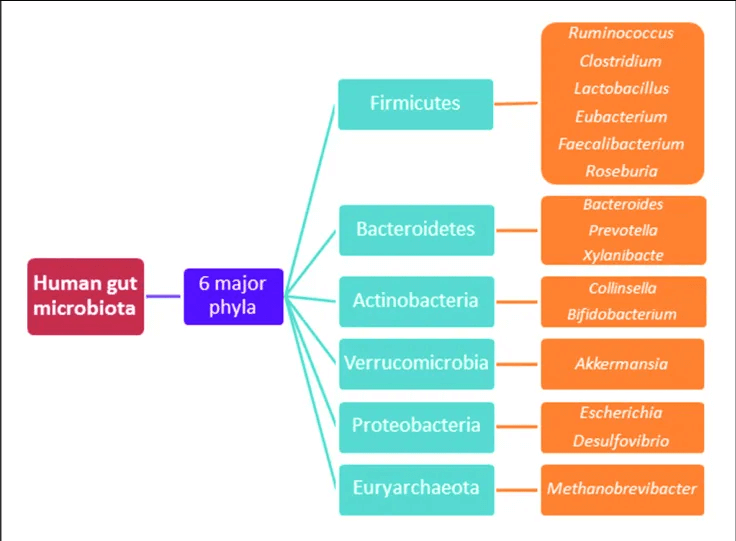

Bacterial species typically come from these 4 phyla: Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria. Most bacteria belong to the genera Bacteroides, Clostridium, Faecalibacterium, Eubacterium, Ruminococcus, Peptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, and Bifidobacterium. Other genera, such as Escherichia and Lactobacillus, are present to a lesser extent. Species from the genus Bacteroides alone constitute about 30% of all bacteria in the gut, suggesting that this genus is especially important in the functioning of the host.

Most bacteria live in the colon, with only few living in stomach (which is a highly acidic environment) and small intestine. 99% of the bacteria in our guts come from about 30-40 total species, and bacteria make up 60% of the dry mass of feces.

Many microbial species in our GI tract are responsible for assisting in processing fiber and other important carbohydrates that play a role in GI health, cardiovascular function, and more.

Commensal bacteria participate in a phenomenon called microbial antagonism: meaning they take up the real estate in and on our bodies to prevent pathogenic microorganisms from colonizing and potentially causing illness.

In addition, commensal bacteria help educate our immune system: they train immune cells to differentiate between benign microbes and disease-causing microbes (pathogens), so that your immune system reacts appropriately under different conditions.

While know mouse models are not indicative of what occurs in humans, although animal studies are useful to start providing insight as to potential mechanisms.

A fecal transplant is much more efficient at transferring microbiota (as it isn’t going through the GI tract), but these studies give some insight as to the importance of gut microbiota in helping to modulate health/weight/metabolism.

The complexity and importance of the microbiome is exploited to sell unproven supplements

Okay, so let’s get back to probiotics. Probiotics are consumed and make their way through our GI tract. As such, they need to be able to survive after being eaten, and make their way to the intestine and colon in order to even have a potential at exerting some positive effect.

Not all probiotics are the same. Different strains of bacteria have different effects. For example, one strain may fight against cavity-causing organisms in our mouths and don’t need to survive a trip through our guts.

When you look at probiotic supplements, you’ll note that they aren’t all the same species of bacteria. This is one inherent issue with probiotics as supplements.

Many companies that produce probiotics grow the type of bacteria that they ‘know how to’ grow, not ones that are actually useful in our gut or that would survive the trek through our GI system. On top of that, only those supplements that have an enteric coating would not be destroyed in our stomachs and actually make their way to the intestine to potentially contribute to the colonization of the microbiome there.

As a reminder, our gut contains around 40 trillion bacteria. In probiotic supplements, there are only between 100 million and a few hundred billion bacteria in a typical serving of yogurt or a microbe-filled pill. That is a drop in the bucket compared to what is normally in our gut.

A 2016 review evaluated 7 trials attempting to address whether probiotic supplements—including biscuits, milk-based drinks and capsules—change the diversity of bacteria in fecal samples.

Only one study—of 34 healthy volunteers—found a statistically significant change, and there was no indication that it provided a clinical benefit. Thus, there is a lack of evidence among healthy individuals that probiotics confer a health benefit.

While mixed data exist related to specifical medical issues, most of these studies have flaws or do not adjust for confounding variables. There are some limited data suggesting a potential benefit of specific probiotics for some things such as infectious diarrhea among children, antibiotic-associated diarrhea, and Clostridium difficile infection.

Some controlled trials have demonstrated no effect of probiotic supplementation with Lactobacillus spp on controlling infectious diarrhea in infants, whereas other studies have suggested a potential improvement in the frequency and duration of diarrhea. Ultimately, studies are limited and data are inconsistent.

Other studies investigating other gastrointestinal issues have also failed to find strong evidence to support the use of probiotics. A randomized controlled trial investigating the role of probiotic supplementation for acute gastroenteritis in children found no difference between probiotic and placebo.

Even a systematic review that included 12 randomized controlled trials investigating the role of probiotics to assist with antibiotic-associated diarrhea concluded that evidence is weak or inconsistent. While the meta-analysis concluded that there is some evidence that probiotic supplementation may be helpful, they emphasize that the evidence is mixed. Other systematic reviews have concluded similarly.

Antibiotic medications are often needed to fight an infection. However, while antibiotics are killing the bad bacteria, they are also knocking out the good bacteria in your body. Some people develop conditions like diarrhea after taking an antibiotic. In other people, this may allow for really harmful bacteria to take over and populate the gut, such as with Clostridium difficile. Ultimately, there is no robust body of evidence to demonstrate efficacy of probiotics even for antibiotic-associated diarrhea.

Some say that probiotics may also be of use in maintaining urogenital health. Like the intestinal tract, the vagina is a finely balanced ecosystem. The dominant Lactobacilli strains normally make it too acidic for harmful microorganisms to survive. But the system can be thrown out of balance by a number of factors, including antibiotics, spermicides, and birth control pills.

Many women eat yogurt or insert it into the vagina to treat recurring yeast infections, a “folk” remedy for which medical science offers limited support, and it can be dangerous. Even unsweetened yogurt has natural sugars, which can fuel yeast growth and might make matters worse. (Vaginosis must be treated because it creates a risk for pregnancy-related complications and pelvic inflammatory disease.)

Anti-fungals (yeast) and antibiotics (vaginosis) are the treatments for these medical conditions. There is early research that is ongoing related to vaginal suppository-based probiotics, but there is no definitive evidence for that yet either.

Probiotic treatment of urinary tract infections is under study. However, a recent meta-analysis of 10 studies in Journal of Pediatric Urology found that probiotics did not have a beneficial effect in reducing the incidence or recurrence of UTI amongst children.

A meta-analysis of 14 studies suggest that probiotics may reduce “gut transit time” by 12.4 hours, increased the number of weekly bowel movements by 1.3, and help to soften stools, making them easier to pass. However, they also stated that the data were mixed, of limited quality, and may be subject to bias.

Probiotic therapy may help people with Crohn’s disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Clinical trial results are mixed, but several small studies suggest that certain probiotics may help maintain remission of ulcerative colitis and prevent relapse of Crohn’s disease and the recurrence of pouchitis (a complication of surgery to treat ulcerative colitis). Because these disorders are so frustrating to treat, many people are giving probiotics a try before all the evidence is in for the particular strains they’re using. More research is needed to find out which strains work best for what conditions.

Colic is excessive, unexplained crying in young infants. Babies with colic may cry for 3 hours a day or more, but they eat well and grow normally. The cause of colic is not well understood, but studies have shown differences in the microbial community in the digestive tract between infants who have colic and those who don’t, which suggests that microorganisms may be involved. A 2018 review of 7 studies (471 participants) of probiotics for colic, 5 of which involved the probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938, found that this probiotic was associated with a reduction in daily crying time. However, the effect was mainly seen in exclusively breastfed infants, and the overall data are limited and not well-controlled.

Necrotizing enterocolitis is a serious, sometimes fatal disease that occurs in premature infants. It involves injury or damage to the intestinal tract, causing death of intestinal tissue. Its exact cause is unknown, but an abnormal reaction to food components and the microorganisms that live in a premature baby’s digestive tract may play a role. A 2017 review of 23 studies (7,325 infants) suggest that probiotic supplements might contribute to prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in very-low-birth-weight infants- (less than 3.3 pounds at birth). However, the results of individual studies varied; not all showed a benefit.

We cannot assume that probiotics are harmless

While none of the infants in the previously-noted studies developed harmful short-term side effects from the probiotic, there are no FDA-approved probiotic supplements for use in infants. There have been over two dozen instances of adverse events occurring in infants directly linked to probiotic supplements since 2018, including one death occurring last year. In addition, because supplements are not regulated, many people do not report adverse events, so these may be underestimating harm.

In several instances, babies developed bloodstream infections from microorganisms intentionally included in a probiotic product, and in one case, a premature baby died after being infected with a mold that had contaminated a probiotic dietary supplement.

There may be risks associated with probiotic supplements especially among individuals with immunological issues: specific disease processes, immunosuppressive medications, or an immature or aging immune system. Unfortunately, probiotic supplements often target these very people: those who are enticed by the purported benefits of probiotics for immune system health.

There are certain people who need to use extra caution when using probiotic supplements, as there can be risk of infection. These include those who have:

- A weakened immune system (those going through chemotherapy for example).

- A critical illness

- Recently had surgery

- Young children and infants

Ultimately, you should never start a probiotic supplement without speaking with a trained clinician.

Just as with vitamins and minerals (and other supplements) probiotic supplements may make claims about how the product affects the structure or function of the body without FDA approval, but they aren’t allowed to make health claims, such as saying the supplement lowers your risk of getting a disease, without FDA consent (and data supporting these claims).

If a probiotic is marketed for treatment of a disease or disorder, it must be FDA-approved as a medication

And guess what? There are NO probiotics that have been FDA-approved as a live biotherapeutic product (LBP).

Over the counter probiotics are considered dietary supplements and are NOT regulated for safety, efficacy, or quality by the FDA.

If a probiotic is going to be used for treatment, it must undergo clinical trials and demonstrate it is safe and effective for its intended use and be approved by the FDA before it can be sold.

If you noticed above, an infant death was linked to mold contamination in a probiotic supplement. Unfortunately, because dietary supplements don’t have quality control oversight, this means that manufacturing processes are not necessarily stringent, opening the door for potential contamination that can cause harm.

While, for the most part, probiotic supplements can be generally viewed as safe, there are not robust studies that actually assess this in detail, so there is not a solid body of evidence to evaluate the frequency and severity of side effects.

Remember: these supplements contain living microorganisms that are metabolizing things and producing byproducts. In addition, adverse effects can include infections from the microbes contained in the supplements, transfer of antibiotic resistance genes from probiotic microorganisms to other microorganisms in the digestive tract. Some probiotic products have been reported to contain microorganisms other than those listed on the label. In some instances, these contaminants may pose serious health risks.

Ultimately, the data show that most of the health claims for probiotics are pure hype

The majority of studies to date have failed to reveal any benefits in individuals who are already healthy, and even studies evaluating specific medical issues frequently report conflicting results that are not robust.

There’s no compelling reason to pay money for probiotic supplements or drinks, especially when the benefits do not outweigh potential risks.

Even in the context of fermented foods: while most of these are nutritious and delicious, there’s also no body of evidence they are offering a unique benefit to your health. If you like pickles, kimchi, yogurts, cheeses: go for it! (I personally love them). But don’t be misled by marketing claims that aren’t supported by evidence.

Andrea Love, a microbiologist and immunologist, provides the facts (and the data!) on science and health topics. Dr. Love is a GLP contributing writer and editor. Many of her articles, like this one, were posted originally, in whole or part, at Immunologic. Follow Andrea on X @dr_andrealove