Two researchers at the University of Warsaw developed a quantum-inspired super-resolving spectrometer for short pulses of light. The device designed in the Quantum Optical Devices Lab at the Centre for Quantum Optical Technologies, Centre of New Technologies and Faculty of Physics UW offers over a two-fold improvement in resolution compared to standard approaches. In the future, it can be miniaturized on a photonic chip and applied in optical and quantum networks as well as in spectroscopic studies of matter.

The research has been published in Optica.

Colors bring information

The task of spectroscopy is to study the various colors, that is the spectrum, of light. A chemical substance will emit its characteristic colors by which it can be identified. Similarly, a distant star will also have a specific spectrum of light, through which its astrophysical properties such as size or age can be understood.

Different colors of light are also used to transmit information over channels in fiber networks, similar to different radio bands that are used to transmit many channels at the same time. These optical channels are at the core of intercontinental optical networks, and are also essential for future secure quantum networks. In all those cases, a difficult task is to distinguish close-by channels or spectroscopic lines.

It has been thought that if channels overlap, they are almost impossible to distinguish—a property studied by John William Strutt, Lord Rayleigh, later termed Rayleigh criterion.

Quantum to the rescue

Progress in quantum information science has allowed researchers to understand that the traditional so-called direct imaging or spectroscopy discards part of the information that is carried in the phase of the complex electromagnetic field of light. The quantum-inspired super-resolution techniques transform the complex electromagnetic field before it is detected to optimally use this latent information.

The working principle of the device—Super-resolution of Ultrafast pulses via Spectral Inversion (SUSI)—is very similar to the so-called quantum-inspired super-resolution methods in imaging. The greatest challenge was how to translate these ideas to the realm of time and frequency.

In super-resolved quantum imaging, the light coming from the object is split into two arms of an interferometer. One arm contains a device which inverts (flips) the image. Then the inverted part interferes with the original one. Now, for instance, if there is only one tiny emitter perfectly aligned with the inversion axis, its inverted image will be identical to the original one.

In this case, the researchers would see no photons in one of the interferometer ports. However, as soon as the emitter was moved, its inverted image will become different from the original and photons will appear in that port. Their number is a very good indicator of how much the emitter was moved. Taking this example a step further, imagine two emitters which are separated symmetrically around the inversion axis.

Each emitter will contribute to the counted photons in the same way, hence they measure the separation between two emitters. As with every measurement, it has a limited precision, but it turns out that this precision can be significantly better compared to just directly imaging the emitters with a camera.

Manipulating time and color

In the realm of time and frequency, these ideas still hold. Instead of thinking about tiny emitters, focus on pulses of light. The pulses appear at the same time but each has a slightly different color, because they come from different optical channels or different spectroscopic lines.

In a standard approach, instead of directly looking at a camera, one would first use a dispersive device such as a diffraction grating or a prism which would send different frequencies to different positions on the camera sensor. With two closely separated pulses, these frequency distributions will mostly overlap, limiting the precision with which the separation can be measured. With SUSI, this precision can be improved.

But how can inversion over the frequencies be implemented? Solving this problem was a crucial step in designing SUSI. A fundamental observation was that instead of placing an inverter in a single interferometer arm, the researchers could get the same result with a Fourier Transform in one arm and an inverse Fourier Transform in the second arm.

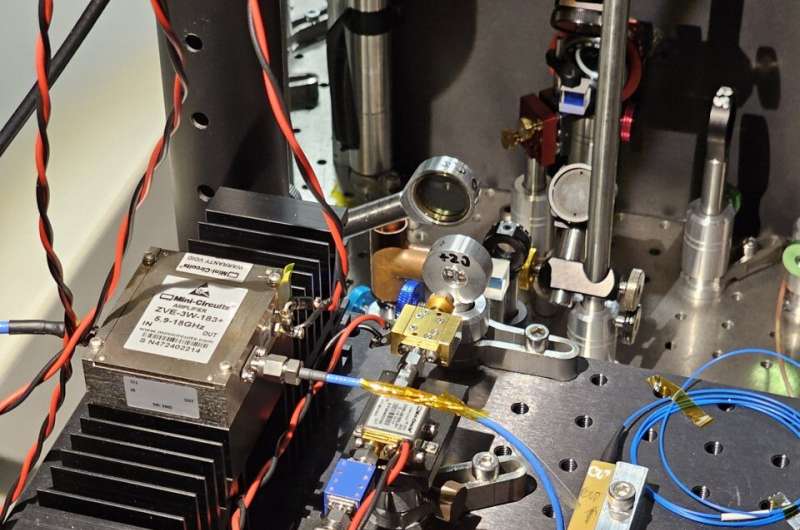

Such a design creates a very balanced and scalable device, which was then built by Ph.D. student Michał Lipka under the supervision of Dr. Michał Parniak, team leader at the Quantum Optical Devices Lab and assistant professor at the Optics Division, Faculty of Physics UW. Both arms of the interferometer have comparable losses, and the devices for the inverse and direct Fourier transform are very similar.

Furthermore, all elements used in the SUSI interferometer can already be implemented on a photonic chip, making SUSI very applicable and integrable in super-spectrometers or devices for optical networks, thus providing at least a two-fold improvement in the resolution compared to current devices.

More information:

Michał Lipka et al, Super-resolution of ultrafast pulses via spectral inversion, Optica (2024). DOI: 10.1364/OPTICA.522555

Citation:

Latent information carried by photons enables super-precise spectrometer (2024, September 12)

retrieved 14 September 2024

from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.