I was astonished to see the Boston Museum of Science elevating completely false information about insect repellents and [chemicals], especially in an area of the country that has one of the highest prevalence of tick species that can cause human illness.

This video repeated false statements about safe and effective methods of preventing arthropod bites, suggested that essential oils are “chemical free,” (and effective), and claimed that they were less toxic and eco-friendly. None of these statements are supported by evidence. Museum of Science also has not responded to any comments about this content.

Misinformation about tick bite prevention leads people to use ineffective repellents, increasing the likelihood they will be bit by insects and arachnids that can transmit potential diseases.

As much as I don’t want to drive further engagement on the post, let me show you what they shared:

What’s more, this video was posted 8 weeks ago, at the start of tick season, and coinciding with the new CDC/HHS National Public Health Strategy to Prevent and Control Vector-Borne Diseases in People, which I attended the public roundtable on just a few weeks ago. During that event, we discussed the 4 pillars of their strategy, which include reducing incidence of infections. Reducing incidence of infections requires reducing the rate of vector bites.

Let’s dig into the facts and the fiction, so you can understand why this content is problematic and what you should be doing instead.

Museum of Science and their collaborator start by asking the viewers “want to stay pest and chemical free?” and segue into a recipe for a DIY insect repellent that is, spoiler: full of chemicals.

Aside from the fact that everything is chemicals, their “formulation” includes rubbing alcohol or witch hazel, plus citronella, peppermint, and/or cedarwood essential oils, all mixed in water (also a chemical).

- Rubbing alcohol, also known as isopropyl alcohol, is a chemical, obviously.

- Witch hazel is a catch-all term for oil extracted from witch hazel plants, normally dissolved in alcohol. Witch hazel liquid can contain anywhere from 50 to over 100 different chemicals, including tannins, gallic acid, catechins, carvacrol, eugenol, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, and more.

- Citronella oil is an essential oil that consists of 30-40 different chemicals, including citonellal, geraniol, limonene, geranyl acetate, camphene, eugenol, methyl isoeugenol, borneol, nerol, linalool, and others.

- Peppermint oil is an essential oil that can contain between 30-90 different chemicals, including menthol, menthone, 1,8-cineole, menthofuran, methyl acetate, pulegone, isomenthone, germacrene D, sabinene, β-pinene, α-pinene, and others.

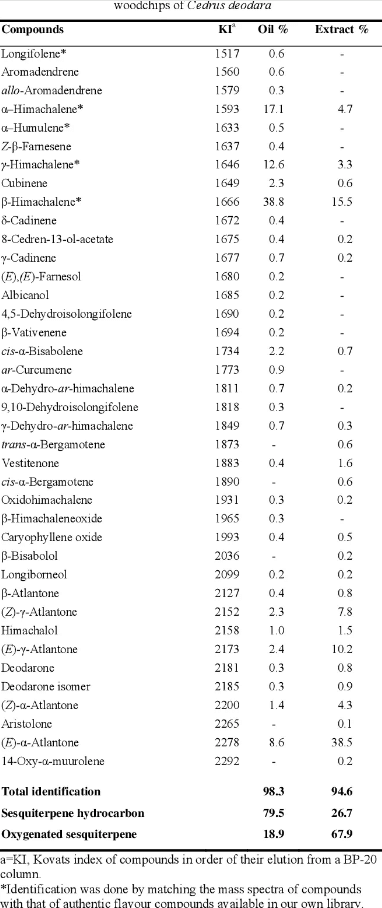

- Cedarwood oil is an essential oil that consists of 50-100 different chemicals, including α-cedrene, β-cedrene, widdrol, cedrene epoxide, cedrol methyl ether, thujopsene, cedrol, caryophyllene, bisabolene, sesquiterpenes, and others.

Ironically, the repellents they demonize, like DEET, use ONE chemical. So, one chemical versus hundreds of different chemicals? Clearly an appeal to nature fallacy, but remember: the source of a chemical has no bearing on its potential harm or safety.

This video claims this homemade repellent is eco-friendly, which is a common misconception about essential oils. Essential oils are called such as they are chemical mixtures isolated from plants that are considered to be “essential” to the odor and identity of the plant in question.

Guess how they’re produced? By growing and then killing and harvesting copious amounts of the plant in question.

Peppermint oil? Peppermint plants.

Cedarwood oil? Cedarwood trees.

Citronella oil? Lemongrass plants.

In order to produce essential oils, they must be extracted from plants, and the plant material required is orders of magnitude greater than the yield of the oils. For example, the cedarwood oil yield is about 1% compared to the mass of the trees.

That means 100 kilograms of cedarwood would be required to product 1 kilogram (1 liter) of cedarwood oil.

That means destructive farming practices, intensive land usage, overharvesting of plants, detrimental impacts to biodiversity. That doesn’t even mention the energy and equipment required to chemically extract the oils from the plants, which, hate to tell you, is done in a laboratory (just like synthetic chemical processing).

So let’s cease and desist with the appeal to nature fallacies and greenwashing when it comes to extolling the unfounded benefits of essential oils.

It is exhausting that these fallacies that have been debunked over decades continue to persist and are being circulated by a science-adjacent account like the Boston Museum of Science. DEET and picaridin, the two recommended and effective repellents, are not impacting our health or the ecology.

It is not an insecticide, so it does not kill insects (including pollinators).

It does not bioaccumulate in ecosystems, and is broken down rapidly by microbes in the soil.

It does not pose a risk for mammalian species or other wild animals.

Remember: the dose makes the poison for anything.

In fact, many essential oils (including those listed above) can be severely irritating to the skin, and can be particularly harmful for young children and pets, so it’s unclear why this nuance was omitted from this discussion. In fact, the “natural” insect repellents you can purchase at the store containing Oil of Lemon Eucalyptus (OLE) have explicit warnings on them to not use them on children under 3 for the potential harms they may cause.

(worth noting: OLE is not sufficiently effective against ticks. As someone who has lived in the epicenter of Lyme her entire life, I would not recommend using it, even though it is listed on the EPA website. The duration of protection of OLE is extremely variable and is impacted by formulation and purity – since it is essential oil-based. The duration is always less than DEET and picaridin).

This is an obvious example of the appeal to nature fallacy along with missing basic principles of toxicology.

Permethrin is not a component of insect repellents that would be applied to the skin. Permethrin is an insecticide, meaning that it kills insects. It is applied to clothing as an added layer of protection against insects and arachnids, entirely separate from insect repellents.

While this may seem a tiny bit nitpicky, it actually is a very important differentiator, something that Museum of Science also gets incorrect.

This should have been disqualifying enough. As someone who has worked in the vector-borne disease field for quite some time (and now serves as the Executive Director for the American Lyme Disease Foundation), I cannot overstate the harms of this type of content. 95% of Lyme disease cases occur in 15 states in the Northeast and Midwest US, including, Massachusetts (where Boston Museum of Science is located).

The fact that an account representing a science museum that likely has a high viewership in New England is spreading misinformation about what people should use as repellents to prevent vector-borne diseases comes across as irresponsible and reckless.

There is so much attention and anxiety about tick-borne and mosquito-borne diseases. Yet we have safe and effective repellents that can dramatically reduce people’s risk of being bitten and potentially getting infected with pathogens. But unfortunately, people are not implementing those measures, and instead are being misled by posts like this that cause unfounded fears about their safety and discourage people to not use them.

This, perhaps, was the part that was most egregious, because these claims are going to put people at unnecessary risk.

To prevent vector-borne diseases, we must prevent vector bites. And we cannot do that when people are spreading falsehoods about effective methods to prevent bites, while legitimizing INEFFECTIVE methods.

Museum of Science did not reply to my messages, which was also disappointing. But let’s get into what’s REAL about insect repellents:

I can’t say this enough. These are the ONLY TWO repellents that have robust data to demonstrate they prevent tick bites.

Repellents do not kill ticks, but affect their sense of smell and taste. When applied, ticks cannot detect humans in their vicinity, which ultimately prevents tick bites. These two chemicals are safe and effective for anyone 2 months and older and during pregnancy. Neither kill insects/arthropods, they work by rendering their ability to detect us less effective.

DEET (N, N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) is an insect/arachnid repellent that was developed in 1946 by the U.S. Army. It has been used by the general public since 1957.

DEET has decades of safety and efficacy data. (Do NOT confuse DEET with DDT, which was an insecticide of completely different chemistry that was banned in 1972).

DEET primarily works through two mechanisms:

- DEET interferes with olfactory receptors in insects and arachnids, which prevents them from detecting chemicals that humans emit that normally alert ticks to our presence: carbon dioxide, lactic acid, etc.

- DEET also elicits avoidance behavior among arthropods. When an arthropod comes into contact with it, interaction with sensory neurons causes confusion and deters insects or arachnids from landing on you and biting.

These two mechanisms reduce attraction to us and ultimately the likelihood and frequency that we will be bitten.

DEET is safe for everyone aged 2 months and older, including during pregnancy. While you can always find a dissenting paper (for any topic, really), the scientific body of evidence (and consensus) demonstrates that DEET is safe for use. More than that, it is one of the only effective methods for repelling pests such as ticks and mosquitoes that can spread a variety of infectious diseases to humans.

Picaridin/Icaridin (1-piperidinecarboxylic acid 2-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-methylpropylester) is an insect/arachnid repellent that was developed by Bayer in the 1980s.

Picaridin was licensed for use in the US in 2001, and has been widely available here since 2005 after EPA approval. It has been used in many other countries globally for longer: Germany and most of Europe since 1998, Australia since 2000, Japan, China, India, and others in the early 2000s. Just like DEET, it also has decades of data to demonstrate safety.

Picaridin has a slightly different mechanism of action compared to DEET. Instead of directly binding and interfering with olfactory receptors, picaridin reduces the level that which chemicals that humans produce evaporate from our bodies (the volatility). These chemicals that we secrete are smelled by insects when they evaporate, so reducing that masks our presence to insects/arachnids and reduces our likelihood of being bitten.

When applied to the skin, these chemicals evaporate and form an invisible vapor barrier just above our skin (a layer of gas). This is how the chemicals work, which is why applying them under clothing is not going to be effective. This is also why you want to apply them as your top layer, so if you are putting sunscreen and repellent on, sunscreen goes directly onto skin first, then apply your repellent 10 minutes afterward on top.

This is related to the evaporation rate: once you lose the vapor barrier, the repellent is no longer effective.

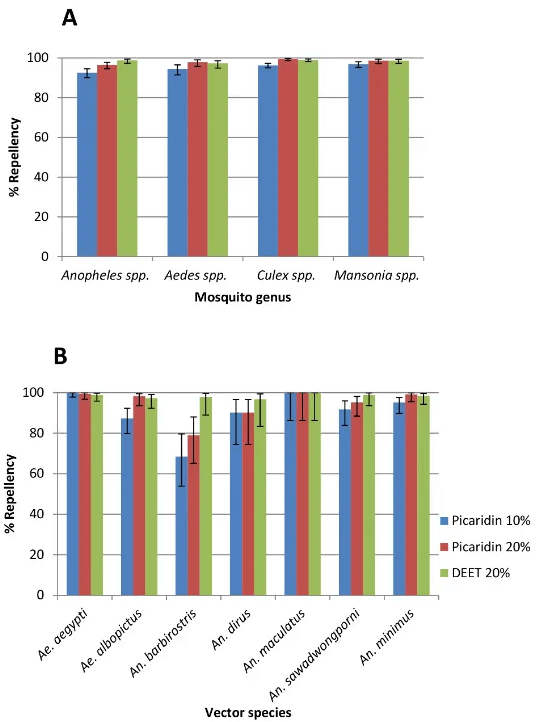

You can find DEET concentrations ranging from 10% to 98%. For tick prevention, 10% DEET will provide protection for about 2 hours, whereas 20-30% DEET will be effective for about 6-8 hours. (for mosquitoes, protection lasts a bit longer). Higher concentrations of DEET will last 8-10 hours, but if you sweat, that will reduce the duration of protection.

Picaridin products typically range from 20-40% concentration. 20% picaridin is effective against ticks for about 6-8 hours, similar to 30% DEET. Some people prefer picaridin over DEET because it is odorless and the texture may be preferable for individuals, but both are equally effective and safe for use for anyone 2 months and older. For kids under 10, you’ll want to apply repellent to them, to ensure it is appropriately applied.

While DEET and picaridin might be demonized by people promoting “alternative” or “natural” repellents, the reality is that those claims are just exploiting the appeal to nature fallacy. That doesn’t even mention the fact that these alternatives do not have efficacy data to support their use as insect repellents. In contrast, DEET and picaridin are safe and effective for repelling biting pests and reducing the spread of vector-borne diseases.

You’ll want to apply these repellents to your skin before heading out to enjoy the outdoors. Using effective repellents is an important step in preventing vector-borne diseases so that you can enjoy the outdoors with more peace of mind.

This type of anti-science and chemophobia-based messaging does immeasurable harm to science literacy and public health. It exploits the irrational fear of “synthetic” chemicals and propagates the false belief that natural chemicals are superior or safer or more eco-friendly, when the source of a chemical does not dictate these features.

It is disheartening that science-adjacent accounts, especially those geared toward kids and their families like the Boston Museum of Science promote this type of content that is not aligned with science education or credible science or critical thinking skills. Our society must do better to address science and health misinformation that is far too pervasive, and is ultimately harming public health, trust in science, and critical thinking.

Dr. Andrea Love, a microbiologist and immunologist, provides the facts (and the data!) on science and health topics. Follow Andrea on Twitter @dr_andrealove

A version of this article was originally posted at Immunologic and has been reposted here with permission. Any reposting should credit the original author and provide links to both the GLP and the original article.