Worsening fires in Brazil’s Amazon are a threat to new initiatives to raise finance for rainforest protection – including carbon credits and investment funds – due to be showcased at COP30 in November, local climate experts say.

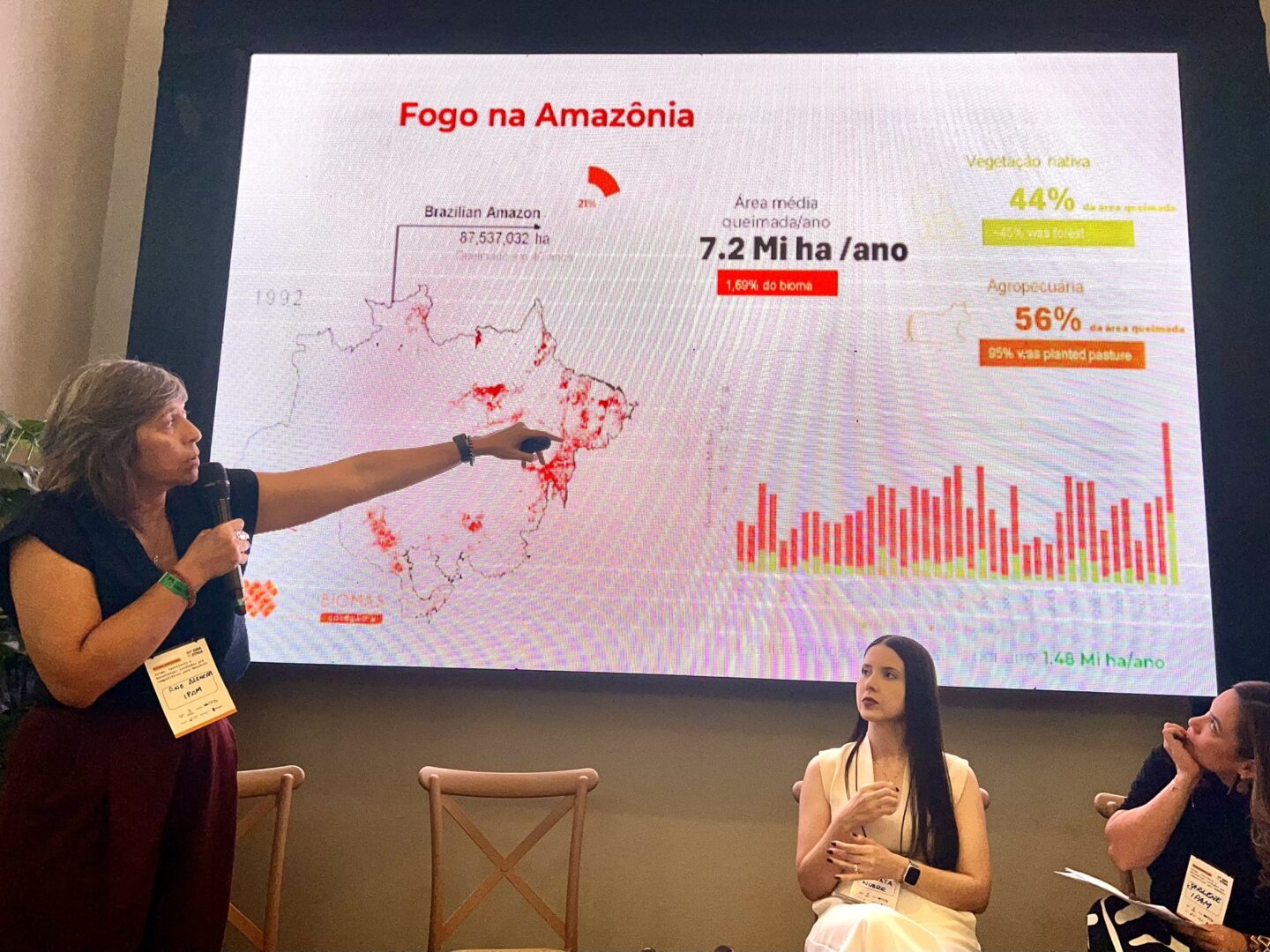

Fuelled by a severe drought linked to climate change, fires in the Brazilian Amazon burned a record 15.6 million hectares (38.5 million acres) last year – an area roughly the size of the US state of Georgia, according to the MapBiomas mapping initiative. Almost half of that was forest, as opposed to pasture or other land.

Fires are also becoming an increasing cause of overall deforestation, reversing progress to tackle other kinds of forest destruction under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. In May 2024, fire accounted for 51% of Amazon forest loss, up from 21% in the same month a year earlier, data from the BiomasBR monitoring programme shows.

Fires not only devastate the forest and increase carbon emissions from the burned trees, but could also undermine longer-term efforts to fight deforestation, said Ane Alencar, science director at the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM), a research NGO.

“Initiatives such as payments for environmental services, bioeconomy development, ecological restoration, and nature-based solutions – all these efforts made to reduce emissions from deforestation can be affected because there have been forest fires,” Alencar told Climate Home News in July, when the fire season normally starts.

Risk for TFFF or call for action?

During the UN climate conference in the city of Belém, COP30 president Brazil will launch conservation initiatives including its Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF) blended-finance mechanism, which aims to generate a flow of international investment to pay countries annually in proportion to their preserved tropical forests.

If fires in the Amazon continue to worsen in the years to come, eligibility for funding could be jeopardized, Brazil’s Environment Ministry acknowledged.

“As with all countries participating in the TFFF, if the deforested area surpasses the mechanism’s eligibility limit, the country will lose the right to receive payments that year,” the ministry told Climate Home in emailed comments. To be eligible, a country’s new deforestation cannot exceed 0.5% of its total forest area.

Images of smoke and flames billowing across the rainforest are also bad news from a PR perspective at a time when some countries have already “expressed reluctance to support the TFFF due to their responsibilities related to the new climate finance target approved at COP29,” said Ciro Brito, senior climate policy analyst for the Instituto SocioAmbiental, a Brazilian NGO.

“In that context, factors such as the increase in fires in Brazil directly affect engagement around the TFFF and may hinder further commitments,” Brito said.

But the growing fire threat makes the TFFF all the more vital and urgent, said Natalie Unterstell, president of the Talanoa Institute, a climate policy think-tank based in Rio de Janeiro.

“Arriving at COP30 with negative fire indicators will, without a doubt, serve as a warning. But it should be read as a call to action,” Unterstell said.

“An increase in fires in the Amazon this year does not weaken the TFFF proposal … On the contrary, it reinforces the urgency of creating innovative financing mechanisms,” she added.

PR firm working for Shell wins COP30 media contract

Carbon credit troubles

Rainforest ecosystems rarely burn naturally, but in recent decades, drought and deliberate fires set to clear land for agriculture have fuelled the threat to the forest from fire.

In the state of Pará – where COP30 will be held – the surge in wildfires could be another blow for the state government’s troubled REDD+ carbon credit project.

“To generate credits, we need proven emission reductions … So, what good is all our work to reduce deforestation if we lose it all to fire?,” Renata Nobre, adjunct secretary of water resources and climate at Pará’s environmental secretariat SEMAS, told a panel on fires’ impact on Amazon investments at an event last month in Belém.

Deforestation via clear-cutting fell in Pará last year, but fire damage skyrocketed. Pará’s forest degradation – a category covering fires as well as selective lumber extraction – soared nearly 500%, according to the Imazon research institute.

Last year, the state signed a carbon credits deal worth $180 million with the LEAF Coalition, a public-private partnership including US retail giants Amazon and Walmart, and the US, British and Norwegian governments, among others.

In June, federal prosecutors filed a lawsuit against the project, arguing that the deal was invalid because it violates Brazil’s federal carbon market law and because Pará lacks a legally approved system to emit carbon credits. They also said state authorities had failed to hold proper dialogue with forest communities.

Forest fires are another potential problem for the REDD+ project, and in turn the state’s potential income for environmental protection services such as firefighting, said Andrea Azevedo of Emergent, an NGO that administers the LEAF Coalition contracts.

“But if fires increase, as we saw in 2024, this translates into losses for the state, directly impacting its ability to fund these (fire control) policies,” she told the panel in Belém.

In 2023, Pará’s forest loss fell within contractual limits stipulated by the LEAF Coalition as part of the programme, according to an email from the Pará Environmental Assets and Participation Company (CAAPP) – the public-private company tasked with channelling funds raised from carbon credit sales to beneficiaries.

But it is still unclear whether 2024’s fires could put Pará over the predetermined emissions targets.

“Only once accounting is complete will we know how much emissions reductions actually occurred and how it relates to the baseline the state adopted,” said Joice Ferreira, a scientist at the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) and a CAAPP board member.

“Shortfalls below projections do not (alone) constitute a (contract) breach”, because the state only sells verified emissions reductions, Ferreira added.

Firefighting efforts ‘not enough’

Both at the federal and state levels, authorities in Brazil have been ramping up firefighting initiatives and funding to respond to the growing threat.

In Pará, land management programmes for farmers warn against starting fires to clear vegetation, while a new state fire plan launched in 2024 includes the use of satellite sensors, and public-private partnerships to supply equipment and vehicles.

Local brigade training has also been stepped up. Indigenous firefighting teams like those in the Suruí Aikewara Indigenous territory prove that brigade training can work, said village chief Yrykwa Suruí.

“We haven’t had a big fire (since 2017),” Suruí told Climate Home, explaining how training and financial support from the federal Ibama environmental agency has been used to teach community members to stop flames spreading when fires are set to clear plots for crops.

Despite such efforts, stemming the fires in Pará’s vast, forested interior is a huge challenge.

“In 2024, we saw an exponential increase in fire outbreaks – our efforts were simply not enough,” said Nobre, the state official.

As COP30 draws near, the growing fire threat and its links to climate change make a global response all the more urgent, said Leonardo Sobral, forest director of Brazilian non-profit Imaflora.

“The increase in fires will only highlight the need to implement financial mechanisms that value standing forests as fast as possible. It is urgent that mechanisms like the TFFF be put into action.”

Unterstell, from the Talanoa Institute, said Brazil’s leadership at COP “will be judged by its ability to respond to this crisis with concrete and sustainable solutions.”