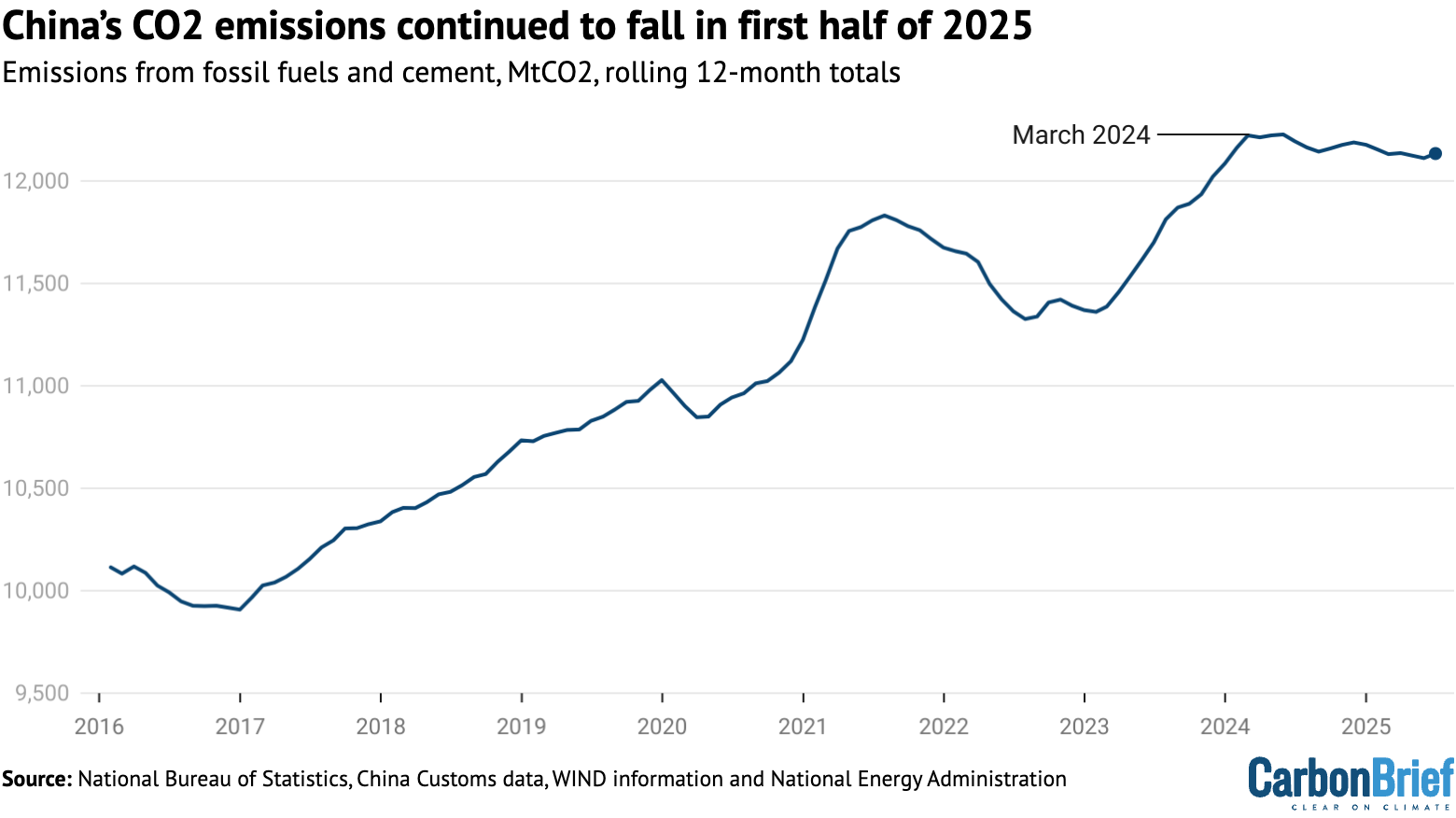

While China’s planet-warming emissions keep falling, its growing use of coal to produce liquid fuels and chemicals – including plastics – risks threatening its climate goals, a new analysis has shown.

Record installations of solar power helped extend a slight decline in China’s overall carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in the first half of 2025, but the country’s ballooning coal-to-chemicals industry bucked the positive trend, according to analysis by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) for Carbon Brief.

It was the only major sector to see a growth in emissions – with 20% more coal being used as fuel and raw material compared to the same period last year. In contrast with the rest of the world, China increasingly relies on its abundant reserves of coal to produce synthetic fuels and petrochemical products.

Coal-to-chemicals expansion

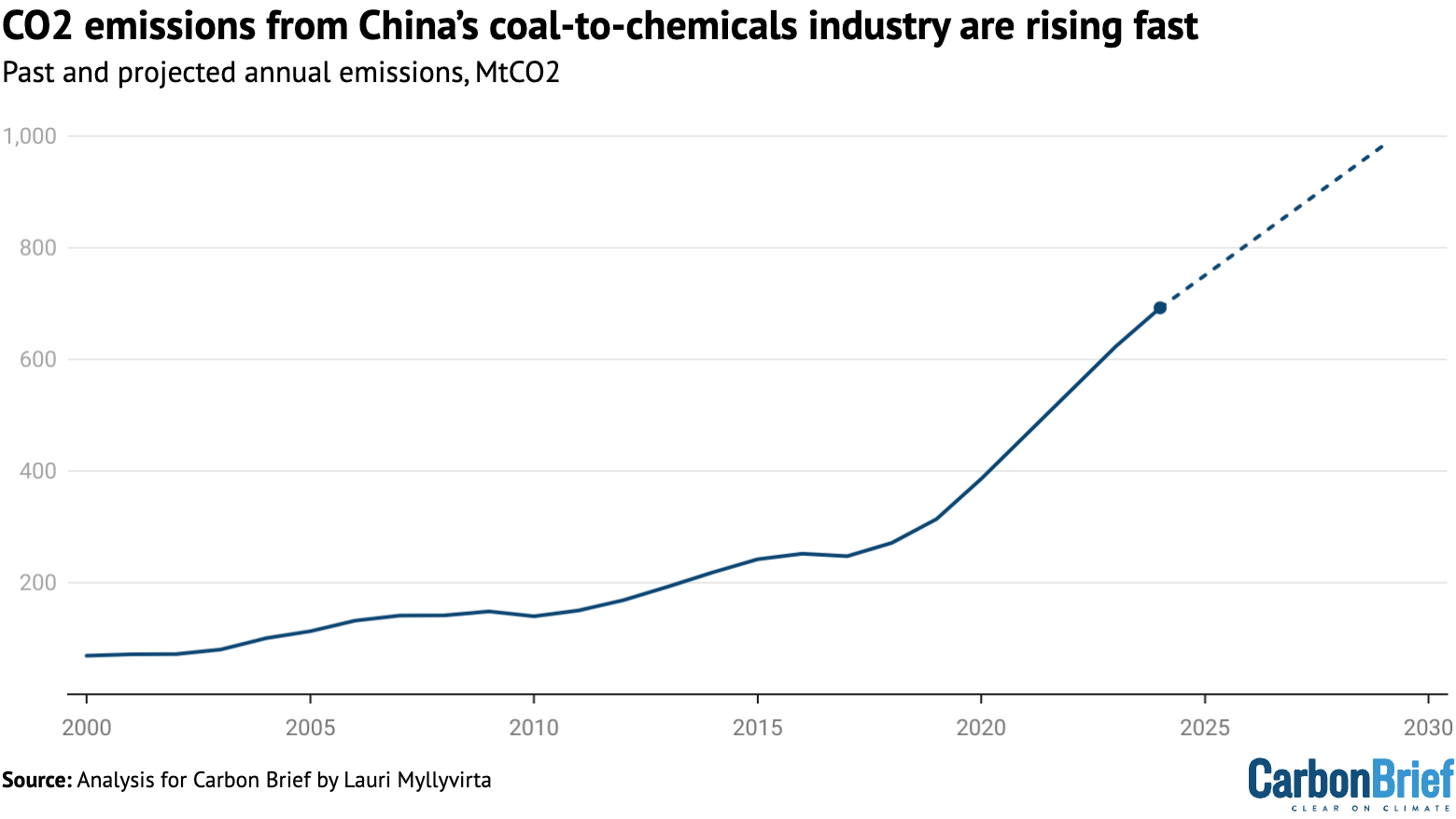

Planned expansion of the coal-to-chemicals sector could add an extra 2% to China’s overall emissions by 2029 and complicate the country’s plans of peaking emissions by the end of the decade, CREA’s research showed.

CREA’s lead analyst Lauri Myllyvirta said that, if realised, China’s coal-to-chemicals growth ambition “certainly makes it harder to reach China’s 2030 climate commitments, to which the country is badly off track as it is”.

Currently, China – which alone accounts for a third of global greenhouse gas emissions – has a goal of peaking CO2 emissions “before 2030” and reaching carbon neutrality by 2060.

Since 2020, the country has also had a pledge to reduce CO2 emissions per unit of GDP – a measure known as carbon intensity – by more than 65% below 2005 levels by 2030.

Coal diversion amid solar boom

The country’s record-breaking rollout of renewables has helped drive down emissions in the power sector. Developers rushed to install 212 gigawatts (GW) of new solar capacity in the first half of 2025 ahead of a policy change on tariffs paid to new wind and solar generators.

In May alone, the equivalent of 100 solar panels per second were added, according to CREA’s analysis.

But, despite its green progress, China still consumes more coal than every other country in the world combined. The majority of it continues to be burned as fuel in power stations and steel furnaces, but growing amounts of coal are being converted into a wide range of chemicals, including ammonia-based fertilisers and olefins, the building blocks for many plastic products and adhesives.

EU “green” funds invest millions in expanding coal giants in China, India

According to CREA’s Myllyvirta, the current boom in coal-to-chemicals stems from “the heightened geopolitical risk perception” during US President Donald Trump’s first term, which prompted China to reduce its reliance on oil and gas imports.

Beijing is also promoting the sector to prop up coal demand in remote top-producing regions like Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang, he added.

Impact on climate plans

As coal-based chemicals production is far more carbon-intensive than its oil and gas-based equivalent, China’s strategy is having a sizeable climate impact. The industry added around 3% to China’s total CO2 emissions from 2020 to 2024, making it one of the sectors responsible for the growth in overall CO2 emissions over that period and for the expected shortfall against key climate targets, CREA’s analysis said.

China’s chemical industry association expects the sector to expand for another decade – until 2035 – even under China’s CO2 peaking target, with some estimates seeing a 40% increase in capacity in the next four years.

But Myllyvirta cautioned that the industry had previously made over-enthusiastic predictions and uncertainty remains over the sector’s development.

While reducing reliance on oil and gas imports is a continuing priority, rapid progress with electrification could have a bigger impact and undermine support for the coal-to-chemicals sector, he said.

“I’m sure investments in coal-to-chemicals will continue, but their scale will be calibrated in the upcoming five-year plan,” he added, referring to the document that guides China’s economic development.

Xi commits China to full climate plan but emissions-cutting ambition still unclear

Like four out of every five countries, China has yet to publish its latest climate plan under the Paris Agreement – known as a “nationally determined contribution” or NDC – with an emissions reduction target for 2035. President Xi Jinping vowed earlier this year that Beijing would produce a comprehensive climate action blueprint, covering for the first time all economic sectors.

But CREA’s Myllyvirta warned that, at home, China has stopped short of applying energy consumption control policies on coal that is converted into chemicals – and could introduce similar exemptions once it puts CO2 emissions controls in place. “It’s important to scrutinise the [new] NDC for whether it leaves the door open to this,” he added.