This article is part of the project Every Last Drop, produced with the support of the Global Commons Alliance, sponsored by Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors. It was produced by InfoAmazonia’s Geojournalism Unit, with the support of the Serrapilheira Institute.

In Georgetown, the capital of Guyana, the rumble of heavy trucks transporting materials for massive construction projects echoes throughout the city. A new bridge over the Demerara River, an artificial island, modern buildings and luxurious hotels stand as symbols of the prosperity promised by the oil industry. Foreigners working for recently established companies have already dubbed it “the new Dubai”.

US fossil fuel giant ExxonMobil dominates oil production in Guyana. In 2015, the company announced one of the world’s largest oil discoveries in the decade since. Its subsidiary, Esso Exploration and Production Guyana, has led the consortium for the Stabroek oil block, a 26,800-square-km area off Guyana’s coast, alongside the American Hess Corporation and China’s CNOOC.

Yet, while expanding its presence, ExxonMobil has also faced legal challenges and accusations of environmental abuses.

The company allegedly ignored environmental licenses in order to boost production and profits across the three active fields within the block, which collectively produce 650,000 barrels a day. With three additional fields approved, daily production is projected to double to 1.3 million barrels by 2027.

The Amazon rainforest emerges as the new global oil frontier

In November 2024, a team from InfoAmazonia travelled to Georgetown and its vicinity to interview key whistleblowers from the oil industry and scrutinise lawsuits and reports revealing ExxonMobil’s environmental violations in Guyana.

The investigation also shows that the Guyanese government eased environmental regulations, signed contracts that benefited oil companies at the expense of the public, and backed the corporations in legal disputes, heralding its emergence as a “petrostate”.

“Our institutions have been captured by foreign interests. Exxon isn’t the only one, but it’s certainly the most egregious,” said environmentalist Sherlina Nageer, founder of the Greenheart Movement, an initiative that advocates alternatives to the oil industry, and one of the main voices opposing fossil fuel exploration in Guyana.

The Amazon basin – which covers eight countries including Guyana – has emerged as the new global oil frontier, holding about 20% of the world’s oil and gas reserves identified between 2022 and 2024, according to Global Energy Monitor data. Most of those reserves remain undeveloped.

But there are widespread concerns around the impacts of extracting those fossil fuels on forest ecosystems and local communities, as well as questions over how far the economic benefits will trickle down to the populations of Amazon countries.

In 2022, ExxonMobil recorded global revenues of US$413 billion – around 28 times Guyana’s GDP, which was estimated at $14.7 billion, according to World Bank data.

Yet, despite the oil boom propelling the country’s GDP growth to 65% in 2022, poverty remains high. The UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) reported that in 2022, 43% of Guyanese lived on less than $5.50 per day per person.

The country’s unemployment rate of 14% is one of the highest in Latin America. Major construction projects, such as the bridge over the Demerara River and modern buildings in the centre of Georgetown, are built by Chinese companies with mainly Asian workers.

Power outages, meanwhile, are constant in the capital. Guyana’s government and ExxonMobil are developing a $2-billion initiative to pipe gas from offshore platforms to power the nation’s electric grid, with ExxonMobil promoting the project as an emissions-reduction strategy.

Irregular gas flaring

Among ExxonMobil’s practices questioned by environmentalists and Guyana’s courts is gas flaring, a practice that burns off natural gas, a byproduct of oil production. This occurs when there is no infrastructure to process the excess gas or no profit in doing so. Flaring releases large quantities of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane, which cause global warming.

The environmental license for the Liza Phase 1 field – Esso’s first discovered reserve – was approved in 2017, prohibiting gas flaring except during maintenance or emergencies. Nevertheless, from the start of production in 2019 through 2023, the oil company reported 1,298 instances of gas flaring, according to data from SkyTruth, a platform that uses satellite monitoring to track activities harmful to the environment.

The analysis, which was conducted with advice from the Arayara International Institute, revealed that from 2019 to 2023, ExxonMobil flared 687 million cubic metres of gas off Guyana’s coast, emitting 1.32 million tons of CO₂ into the atmosphere.

This amount is comparable to the annual emissions from nearly 287,000 cars, making Guyana the second-largest greenhouse gas emitter from flaring in the Amazon, following Ecuador.

Trump follows the minerals trail – but for weapons not clean energy?

Nageer was one of three plaintiffs in a lawsuit against flaring on platforms operated by Exxon subsidiary Esso.

The trio of activists gathered evidence of what they say are illegal activities using satellite images. In April 2021, they alerted the Guyana Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which oversees and licenses the nation’s oil industry.

One month after the complaint, the EPA revised the oil company’s environmental permit, extending the allowable flaring period from three to 60 consecutive days. The revised permit levies a $45 charge for each tonne of CO2 emitted.

When the incident was revealed in August 2021, millions of cubic metres of gas had already been flared. In court, Esso attributed the flaring to a mechanical failure in the gas compression system.

The president of Guyana’s Supreme Court, Roxanne George, eventually issued a ruling in favor of the oil company. “It has not been proven that the modification of the license has caused or is causing additional adverse effects on the environment,” she said in 2023. “There is nothing in the law that prevents the issuance of a modified permit.”

Vincent Adams, a former director of Guyana’s Environmental Protection Agency and an official at the US Department of Energy for 30 years, said the court decision let Esso off the hook. “The government is basically saying, ‘Pollute as much as you want, provided you can pay for it’,” he told InfoAmazonia.

InfoAmazonia repeatedly reached out to ExxonMobil and its subsidiary in Guyana, Esso, but received no response to interview requests for this article. Enquiries were also sent to oil companies Hess and CNOOC, but as of the time of publication, they had not replied.

The Guyanese government was contacted but did not comment.

Unfavourable contract for Guyana

Guyana’s oil exploration controversies predate the granting of licenses, extending back to the initial negotiations. After ExxonMobil discovered the first reserve in the country in 2015, the government had to create the Stabroek Block’s profit-sharing contract from the ground up, including deadlines and percentages for both profit distribution and cost recovery.

The agreement between Esso and Guyana was negotiated privately in 2016 and remained undisclosed until 2017. Only made public after strong external pressure, the contract has faced intense criticism from experts and political figures alike.

The contract stipulates that up to 75% of the monthly gross revenue from the block’s extraction will cover the companies’ development and operating expenses. The remaining amount is split equally between the Guyanese government and the consortium, granting Guyana a 12.5% revenue share.

Governments set to agree fees for ships that miss green targets

The agreement also sets a 2% royalty rate on the value of oil sold, lower than rates in other countries. While rates in Brazil can reach 15%, the US recently updated its royalty rate for exploration on public lands to over 16%.

A report by the US-based Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis highlights that the contract imposes unfavourable terms on Guyana, enabling oil firms to claw back their expenses.

“It’s a very bad contract that deprives us of a lot of resources,” said former Guyana President Donald Ramotar. During his tenure from 2011 to 2015, ExxonMobil conducted surveys off the country’s coast, resulting in the first major discovery.

Current President Irfaan Ali acknowledges the agreement’s unfair terms but insists that the “sanctity of the contract” must be upheld.

Ali has vowed to negotiate improved terms for future contracts. However, this promise might be inconsequential – as all of ExxonMobil’s planned production fields are located within the Stabroek Block, which remains protected under the 2016 contract.

Georgetown Mayor Alfred Mentore, an opponent of Ali, emphasised that the review hinges on political will. “With the help of good lawyers, reaching a consensus is possible,” he said.

While not against exploration, he called for a new approach: “We need to find a balance between our impact on the environment and how we deal with development.”

Communities are apprehensive

Coastal and Indigenous communities near Georgetown, meanwhile, are divided and apprehensive about the expanding oil industry. In Hope Beach, 25 km from Georgetown, sits a graveyard of abandoned boats. “They were used for fishing,” said fisherman Amran Samad, “but people put them up for sale and nobody wanted to buy them.”

Oil extraction has disrupted local fishing, according to locals. They report that heavy ship traffic and vibrations from offshore operations drive away shoals. Meanwhile, an influx of cheap imported fish, linked to the arrival of more foreigners, has intensified competition and reduced demand for the local catch.

In the community of Anna Regina, 60 km from the capital, a sign reads, “The mangroves protect us and our products from the sea. Let’s protect them.”

There, Doodneith Mdehnai, who runs a small stall selling vegetables and fish, shared mixed emotions. “I think oil is good because it brings money and jobs,” he said. However, he hesitated when considering the potential environmental impact: “The mangrove is our source of life. If an [oil] spill hits the mangrove, it will wipe it all out.”

“Most coastal communities are unaware of the potential consequences of an oil spill,” said Nicholas Peters, policy and advocacy coordinator for the Amerindian Peoples Association.

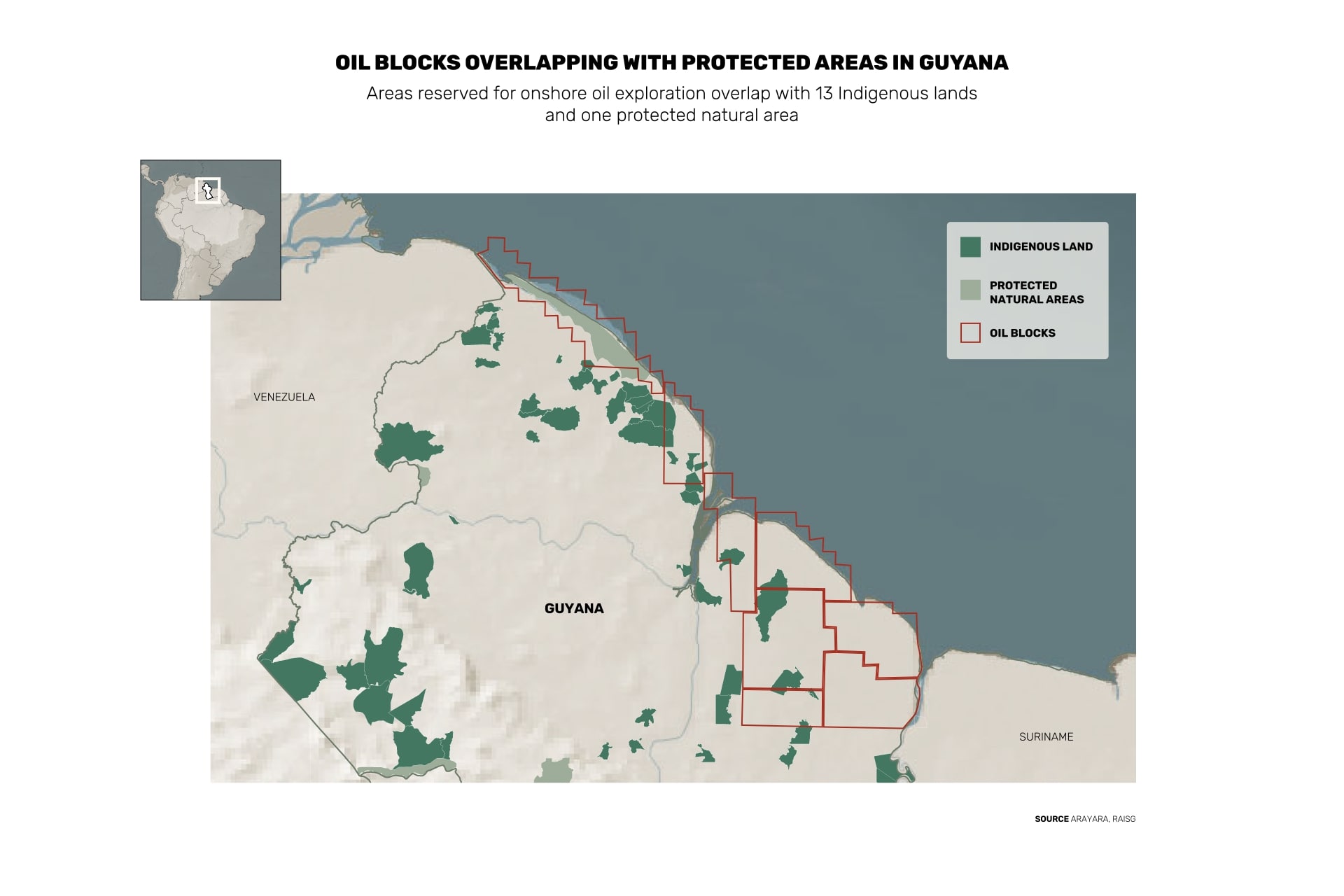

The Every Last Drop project has also found that, alongside offshore production, there are onshore exploration areas that overlap with 13 Indigenous territories and one nature reserve in Guyana.

These areas and their inhabitants are also likely to be affected – not only by the oil business itself but by large-scale efforts to compensate for its greenhouse gas pollution and maintain Guyana’s status as a country with net-zero emissions, thanks to the carbon-storage capacity of its extensive forests.

Doubts over forest carbon deal

In 2022, Guyana signed a deal with Exxon, CNOOC and Hess Corporation to offset the emissions from its oil drilling through the sale of 37.5 million carbon credits over a decade. The $750-million deal encompasses almost all of the country’s forests, including Indigenous territory.

Deforestation and land-use changes have already affected Guyana’s forests and contributed to emissions. If new oil reserves are discovered, emissions from these activities, combined with those from the production chain, could further strain the environment.

“The question arises as to whether, in the future, [Guyana’s rainforest] will be enough to balance this impact,” said Joubert Marques, an environmental engineer at the Arayara institute and a scientific consultant for this report.

In addition, Indigenous leaders interviewed by InfoAmazonia said they were not properly informed about the agreement.

In March 2023, the Amerindian Peoples Association (APA) filed a complaint against the Architecture for REDD+ Transactions (ART), the organisation that authorises the carbon credit scheme. Indigenous leaders argued there was a flawed consultation process that did not record comments by Indigenous people and did not provide translated documents.

The government of Guyana disputed these claims and said that the APA was “was very selective in engaging in the consultation”, adding that its representatives did not attend meetings and accusing them of having political affiliations with opposition parties.

A review process by the ART Secretariat concluded that due process had been followed in setting up the scheme and an appeal by the APA was dismissed.

In 2024, the APA and other organisations published a report arguing that the certification process for the carbon credits in the deal “violated the safeguards” of Indigenous peoples by selling off forests in their territories.

“We are now finding out that our forests may be ‘sold’ to the very companies most responsible for climate issues – the oil companies. However, we Indigenous people remain unaware of what was signed or agreed upon, as there was no proper consultation,” Indigenous leader Mario Hastings told InfoAmazonia.

New global fund for forests is a bold experiment in conservation finance

By 2032, Hess is required to pay the Guyanese government a total of $750 million, with a commitment that 15 percent of the funds will be allocated to traditional communities.

In St. Denny’s, an Indigenous community, 100 km from Georgetown, Councillor Donnet Frederick showcased a vegetable greenhouse funded by carbon credit sales.

“Our community received 80 million Guyanese dollars (about US$400,000) from carbon credit projects. This money was used to create a farm, build a greenhouse and renew our production,” he said.

But Trevon Baird, an anthropologist and professor at the University of Guyana, challenged the concept of “progress” through carbon credits. “You can’t just pour money into communities without considering the cultural and environmental impacts,” he said.