Abdulsalam Musa squats as he chips away at lithium-rich rocks with a chisel and hammer in a mining pit in Nigeria’s northwestern state of Kaduna.

The work is dangerous and backbreaking and the 19-year-old is covered in sweat, but he will earn about 4,000 Nigerian nairas ($2.50) for the day – enough to cover his food costs.

“Sometimes, the pits collapse and if someone is trapped inside, that’s his end,” said Musa, resting his back on the edge of the 250 metre-deep hole he had just been mining.

Lithium is a key ingredient of rechargeable batteries for electric vehicles (EVs) and energy storage that are critical for the clean energy transition, and surging global demand for the light and silvery metal has opened a new mining frontier in Nigeria’s central and northern states, where significant reserves have been found.

To benefit from the global lithium rush, the Nigerian government has embarked on a programme of reforms to formalise the sector – aiming to bring artisanal miners like Musa, who dig most of the country’s minerals out of the ground, into regulated cooperatives and add value to its lithium resources by processing them domestically.

The government also wants to attract foreign investors to the nascent sector as it seeks to diversify its economy away from oil.

The push to benefit more from natural mineral deposits is a priority for a growing number of African countries seeking to pull their people out of poverty – from the Democratic Republic of Congo to Zambia – but they face common challenges to modernise their mining industry and add value to their resources.

Ending poverty and gangs: How Zambia seeks to cash in on the global drive for EVs

In Nigeria, Climate Home found that one of the country’s first lithium processing plants has struggled to deliver on its early promises, highlighting the challenges the West African nation faces in reaping the benefits of the global transition from fossil fuels to cleaner energy sources.

Experts told Climate Home News that outdated and poorly enforced regulations have fostered an informal economy of small-scale miners and middlemen, exacerbating the risk of exploitation and environmental degradation in mineral-rich communities.

Early processing efforts

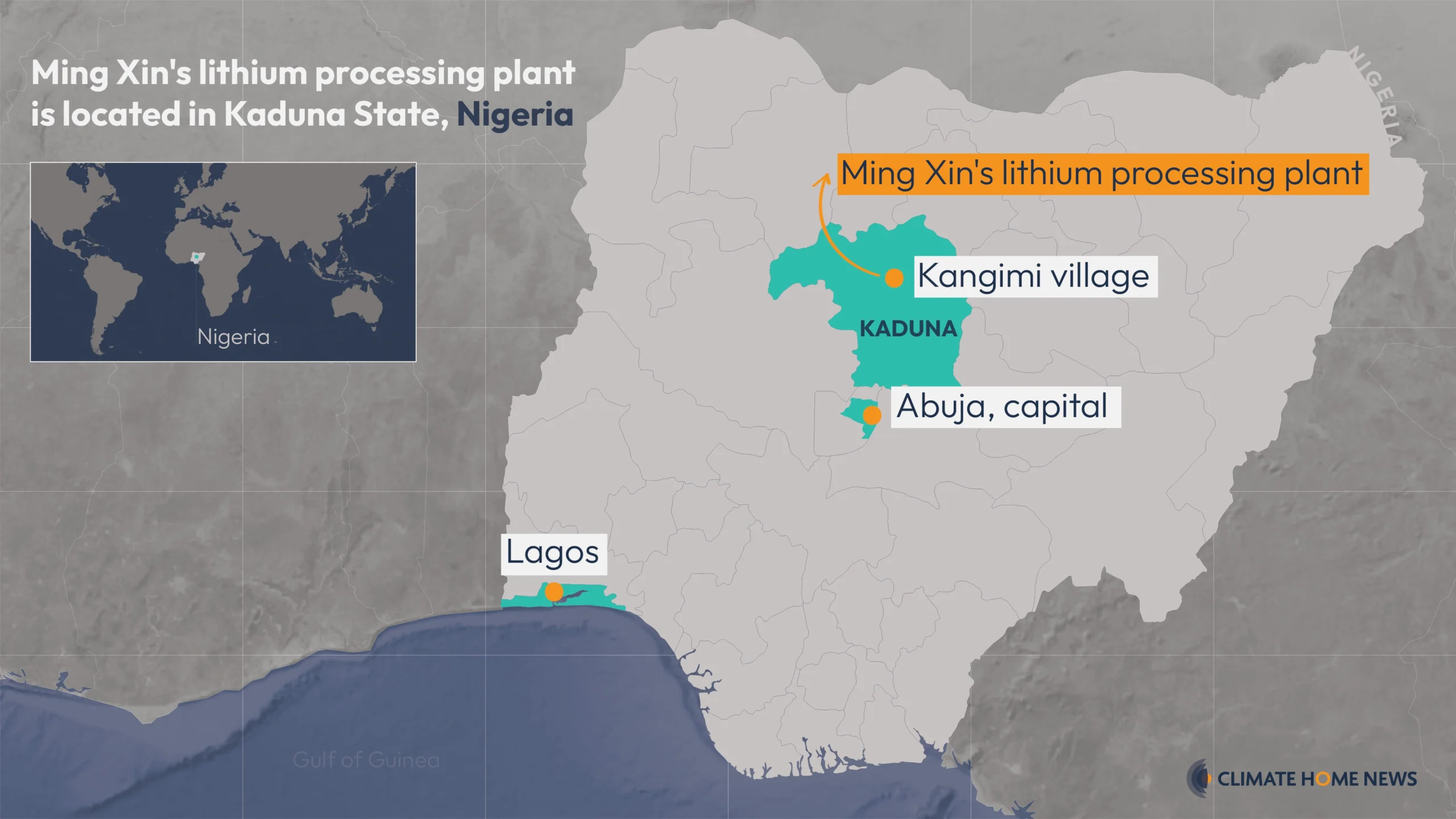

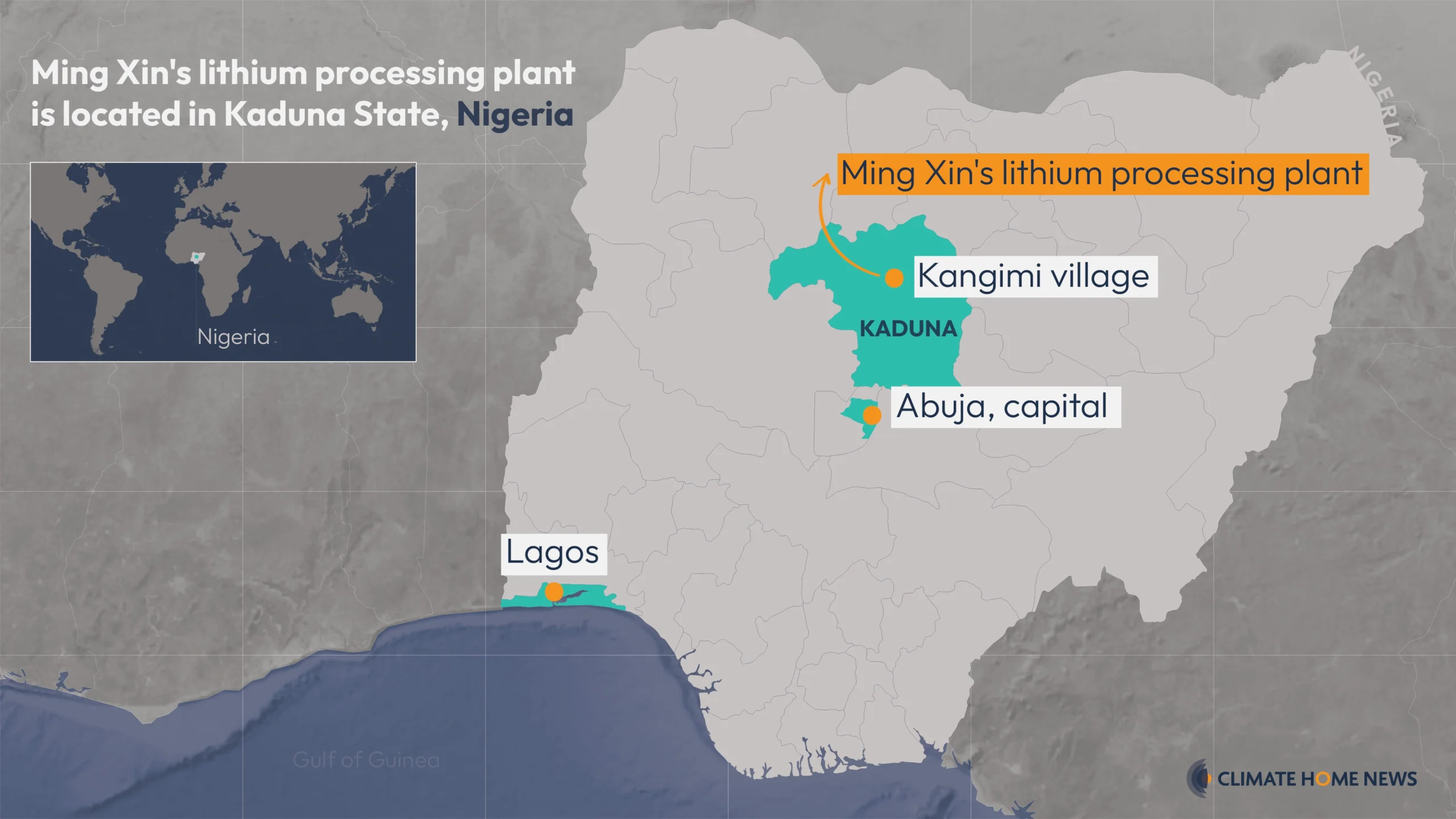

The lithium processing plant inaugurated in the remote village of Kangimi in Kaduna State in May 2024 is a joint venture between the state government and Chinese company Ming Xin Mineral Separation Nigeria Ltd.

In a speech marking the plant’s opening, Kaduna State Governor Uba Sani said the local government would hold a 30% stake in the project through the state-owned Kaduna Mining Development Company (KMDC).

KMDC, which oversees mining activities in the state, would handle “community engagement, all security issues as well as the provision of land” while Ming Xin would run the project, Sani said in a speech.

But a year on from the processing plant’s trumpeted inauguration, it is still not fully operational. Local people said they have yet to see any of the promised benefits materialise, including jobs and improved health and education infrastructure, and are worried about possible pollution.

It is also unclear where the lithium being processed at the site comes from, raising concerns the plant could end up incentivising the informal mining the government wants to regulate.

KMDC officials told Climate Home the refinery remains in its initial phase of development and is awaiting the necessary approval from the federal government to begin operating at full commercial scale. They added that the state company was not directly involved in the plant’s operations.

Ming Xin did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Mining for transition minerals can be responsible with joint push, experts say

The Chinese Embassy in Abuja told Climate Home it had contacted Ming Xin, which said it “holds valid mining licenses and community agreements, has consistently contributed to local communities, created employment opportunities, and always paid rapt attention to protect the local environment”.

“The embassy is willing to work together with the Nigerian side to further strengthen mining cooperation and promote a sound, orderly and sustainable development of China-Nigeria mining partnership, so as to safeguard the common interests of companies from both sides and benefits of both peoples,” the embassy’s statement added.

Nigeria’s burgeoning lithium market has gained the attention of several other Chinese companies and investors. Jiuling Lithium Mining Company and Canmax Technologies are major investors in two new lithium processing plants in Nigeria, worth over $800 million together, which are due to open later this year.

An informal mining sector

Nigeria’s overwhelmingly informal mining sector makes it difficult to trace the lithium produced as it moves along the supply chain.

The ore mined by workers like Musa is bagged in 50 kg sacks and sold to middlemen – some of whom operate illegally without the required licences – who then sell it on to larger traders or exporters.

Some miners and traders use social media platforms, like TikTok and Facebook, to buy and sell minerals, making it even harder for authorities to regulate the trade.

One Facebook group called “Nigeria mineral hub“, which has over 70,000 members, is described as “a verified open market for mineral trade – connecting miners, buyers, and investors across Nigeria and beyond”.

Members advertise various minerals and gemstones they want to sell or buy – including lithium.

Nigeria’s value-added dreams

To break from the pit-to-port export model of the past and capture a slice of the battery-driven lithium boom, the Nigerian government now wants to refine its resources domestically so they can fetch a higher price on the international market.

Last year, President Bola Tinubu directed the Ministry of Solid Minerals Development to only issue mining licences to companies that establish processing plants to refine minerals in the country first.

Explainer: Why the world is racing to mine critical minerals

“We must transition from being merely suppliers of raw materials to becoming globally competitive participants in high-value mineral supply chains,” Nigeria’s Minister of Solid Minerals Oladele Alake told a transition minerals conference at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in Paris in May.

In 2022, the Kaduna State government announced the construction of the lithium processing plant, months after the Nigerian government said it had rejected a proposal from EV giant Tesla to purchase raw lithium from the country for its batteries.

In contrast, Kaduna State hailed Ming Xin’s lithium plant as a flagship value-addition project.

It said the plant would produce 1,500 metric tons of lithium concentrate per day, raise revenue of between 1 billion-1.5 billion Nigerian naira ($650,000- $980,000) per year and create thousands of jobs in a rural farming area that has previously been targeted by violent armed gangs.

The lithium concentrate is destined for export to China, which refines most of the world’s lithium and produces most of its lithium-ion batteries, for further processing into battery-grade lithium.

The processing plant

Speaking to Climate Home by phone, Isah Suleiman, special assistant to KMDC’s managing director, said he didn’t know who was mining the lithium supplying the processing plant or whether the company was already exporting refined lithium.

He said Ming Xin sources some of its lithium from the northwestern state of Kebbi as well as from sites under mining licenses from the Kaduna State government.

Ibrahim Adam, who said he was the processing plant’s site manager, told Climate Home by phone that the company had started sourcing lithium from Kebbi after a bandit attack killed security personnel at a major Kaduna government mining site in 2023.

Two employees at the plant, speaking on condition of anonymity, said refined lithium was leaving the processing plant in trucks.

While Climate Home found no evidence that Ming Xin’s plant buys its raw lithium from unregulated sources, increasing transparency along the country’s lithium supply chain is a growing concern for the government.

Amira Adamu Waziri, senior advisor on mining and policy to Nigeria’s minister of solid minerals development, told the OECD in May that the lack of traceability in supply chains resulted in loss of government revenues and posed “a reputational risk” as “many transactions tend to bypass formal oversight”.

Meanwhile, local people told Climate Home they had so far seen little benefit from the plant.

‘We were failed’

The processing plant sits a few hundred metres away from a dilapidated school building on the edge of Kangimi, a deprived farming village.

Local residents told Climate Home that no community development agreement had been negotiated with local people, despite it being a requirement under Nigerian law.

Danjuma Husseini, Kangimi village head, told Climate Home that Ming Xin made verbal commitments to create jobs for local people, renovate the decrepit school and build a local health facility and a tarred road. But none of the promises have yet begun to materialise.

In a video statement shared with Climate Home, KMDC’s managing director Shuaibu Bello said the plant would create 1,500 direct and 5,000 indirect jobs. But during a visit to the site in March, only 17 local youths were employed to work in roles such as security guards, one employee told Climate Home.

Local people also expressed concerns about pollution. Pits used to wash the lithium ore with acidic chemicals before it is processed are located next to a dam on which residents depend for their sole source of water.

Europe’s lithium rush leaves mineral-rich communities in the dark

During heavy rains, polluted water from the pits overflows and contaminates the water in the dam, according to another employee.

“The company failed us. Their promises were not kept,” said local resident Gambo Abdul, who told Climate Home he had initially been optimistic the processing plant would help improve Kangimi’s infrastructure, including ensuring his 12 children could attend a better school.

In the video statement, KMDC’s Bello said the company had “closely monitored” and helped develop “the proper community development agreement between the company and the community”, including for local people to be first in line for jobs and to ensure the company delivers corporate social responsibility projects.

His special assistant Suleiman added that a committee is being set up to oversee the delivery of community benefits but did not spell out what the agreement with the Kangimi community entails.

Nigeria’s federal government did not respond to specific questions about the processing plant’s operations but it said that Kaduna State, as a partner in the project, was responsible for the plant’s operations.

Segun Tomori, spokesperson for the Ministry of Solid Minerals, told Climate Home that requiring companies to process minerals in Nigeria will develop the mining industry, create employment and generate better export prospects.

Combatting illegal trade

Meanwhile, the government crackdown on illegal mining has already begun.

Minister Alake told the OECD in May that the government had formalised over 1,200 small-scale mining cooperatives and boosted revenue generation from mining fees in the first quarter of 2025.

In addition, the government tasked more than 2,000 mine “marshals” to police the sector. Drawn from the Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps, a para-military government agency, the marshals have arrested 327 “illegal miners” and recovered 98 mine sites that had been occupied by illegal miners in the past year.

“Over 150 illegal operators are undergoing prosecutions and we’ve secured conviction, which is sending a very poignant message to the industry that there is a new sheriff in town. We no longer tolerate illegal operations in Nigeria,” Alake added.

Uche Igwe, governance expert at the London School of Economics Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa, said that the success of the government’s policies will depend on how strongly they are put into practice.

“If you don’t regulate [the mining sector], you create an opportunity for all kinds of actors and all kinds of interests to come and play. So the buck stops at the federal government…to enforce the regulation,” he said.

Main image caption: A young man sorts through lithium ore in Kaduna State (Photo: Sadiq Mustapha)