A group of eight oil- and gas-exporting nations has urged governments not to adopt a pact aimed at cutting the shipping industry’s carbon emissions, saying the deal’s targets are too ambitious and could backfire.

Global shipping accounts for about 2% of total greenhouse gas emissions, but the eight countries said it would be “premature” for the pact to be adopted at a meeting of the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) in October, a written submission to the UN shipping body showed.

They said the pact – provisionally agreed at IMO talks in April despite their objections – contains overly ambitious goals on cutting emissions, would be too costly for shipowners to implement and could disincentivise the use of what they call “transitional fuels” such as biofuels and liquified natural gas (LNG).

Bryan Comer from the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), a nonprofit research organisation, told Climate Home News the countries were “trying to kill” the agreement to shield their sales to the shipping industry, which still mostly uses oil-based fuels.

He said playing up the risk that gas and biofuels could be disincentivised looked like a “scare tactic” given that shipowners have been investing on vessels which can run on LNG- a cheaper and more accessible option than greener alternatives based on hydrogen.

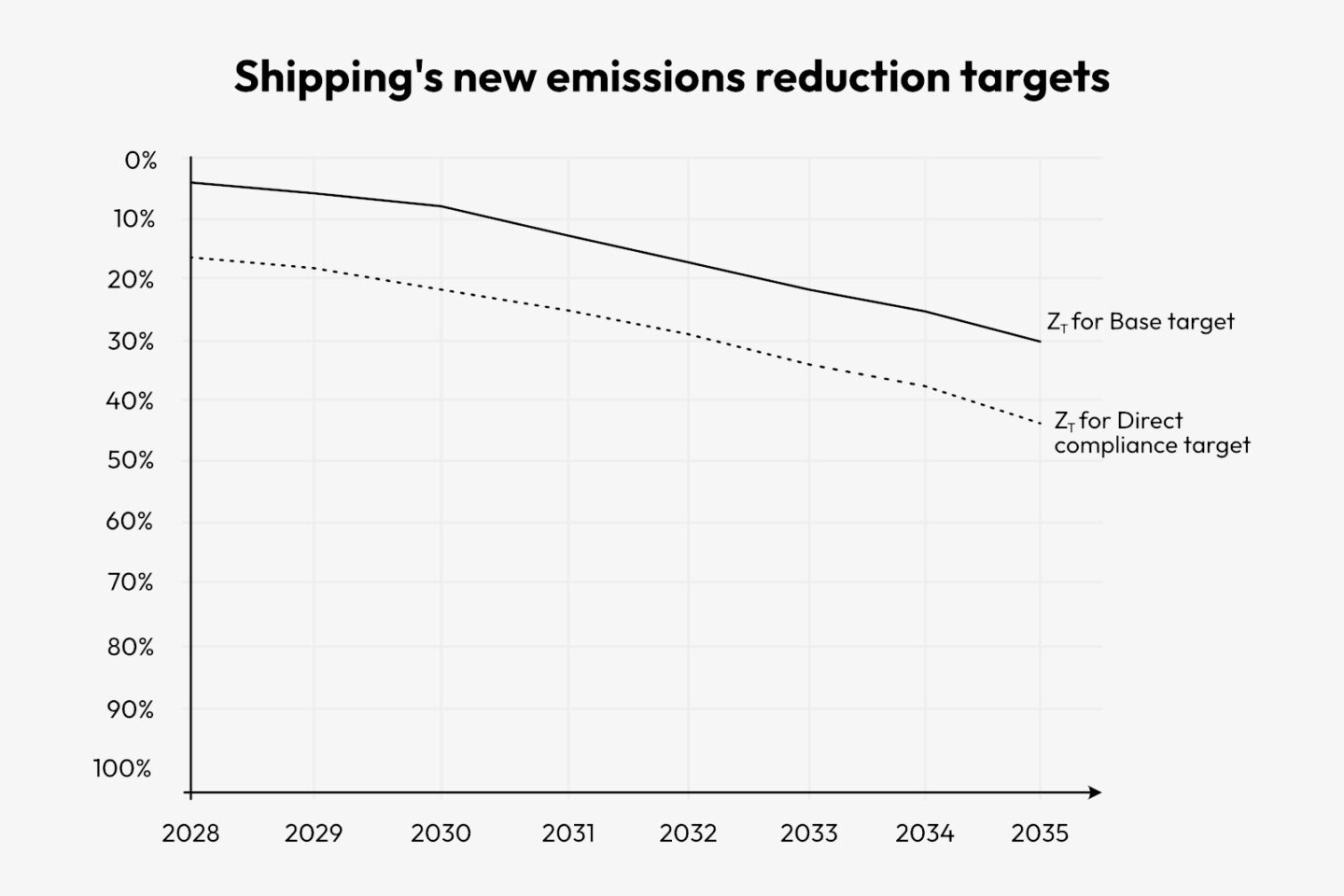

Under the IMO’s Net-zero Framework, governments agreed to set targets to reduce emissions for all the world’s big ships and to financially penalise shipowners who miss these targets.

“Unlikely to succeed”

Another green shipping expert, who asked not to be named, told Climate Home the push to stymie the pact was unlikely to succeed, given that it was overwhelmingly endorsed at April’s IMO talks in London where 63 countries indicated their support for the deal, against 16 who opposed it.

“If petrostates weren’t complaining, it would be a sign the IMO had done something wrong”, they said.

The eight countries that signed the submission are Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Iran, Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Yemen and Venezuela.

They say that the targets to reduce emissions are too “steep” and that shipowners will be unable to meet them, forcing them to “pay to comply” instead.

That money will go to the IMO’s new Net Zero Fund, which will be used to reward shipowners who use cleaner fuels, help workers through the green transition and compensate poorer countries if the switch to greener shipping harms their economies, including by driving up imported food prices.

According to the submission by the oil-producing countries, shipowners will pay an “excessive” amount into the IMO fund, reaching between $59 billion and $161 billion a year in 2040.

Emma Fenton, senior director of climate diplomacy at nonprofit policy group Opportunity Green, questioned that estimate, citing University College London’s estimate of about $11 billion a year by 2030 – “a far cry from what’s needed”, according to Fenton.

“Transitional fuels”

The submission warns that, because of the “steep and progressively more stringent” emissions reduction requirements, “lower-carbon transitional fuels” are “inadvertently de-incentivised”.

“As a result”, it continues, “transitional fuels of any nature (biofuels, [liquified natural gas]) will therefore have a limited, if any, role in the decarbonization pathway”.

Fenton said disincentivising these fuels would be a good thing, because their emissions can be high. Biofuels are made from organic material including sugar, corn, oil palm and soy or animal fats, and are sometimes linked to deforestation.

While gas produces less emissions than oil-based fuel when burnt in the engine, Fenton said these emissions savings can be cancelled out by the gas leaking into the atmosphere as it is extracted and transported.

The viability of both gas and biofuels will be largely determined by the IMO’s official estimate of their emissions intensity – which advocates for these fuels and critics are battling over. These estimates should “takes these non-solutions out of the running”, Fenton said.

Ports with green fuels will be “winners”

The oil-producers’ submission says that, under the net zero framework, ports which have facilities to enable ships to fill up with zero or near-zero emission fuels – like hydrogen-based methanol and ammonia – will be “winners”.

“As a result,” they say, “ships operating between these well-equipped ports will gain an undue advantage, while other ships and sectors will find themselves paying to comply with regulations, effectively subsidizing the compliant ships”.

“Such an outcome undermines both the equity and environmental integrity of the framework, ultimately limiting its effectiveness and acceptance across the sector”, they add.

Fenton agreed that “global inequities in access to sustainable fuels is a key challenge to a just and equitable transition”, but added that “the solution lies in raising ambition not rolling back” and using the net zero fund to develop ports’ infrastructure.

Speaking after April’s IMO talks, Tuvalu foreign minister Simon Kofe told Climate Home he would like to use the fund to install zero-emission fuel infrastructure at his Pacific island nation’s port.

Fenton said it was “unsurprising that actors who always opposed an ambitious net-zero framework will keep trying to water it down”, adding that their objection should not deter delegates “from seeking greater ambition”.