This article, published originally by InfoAmazonia, is part of the project Every Last Drop, produced with the support of the Global Commons Alliance, sponsored by Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors.

The Amazon now holds nearly one-fifth of the world’s recently discovered oil and natural gas reserves, establishing itself as a new global frontier for the fossil fuel industry.

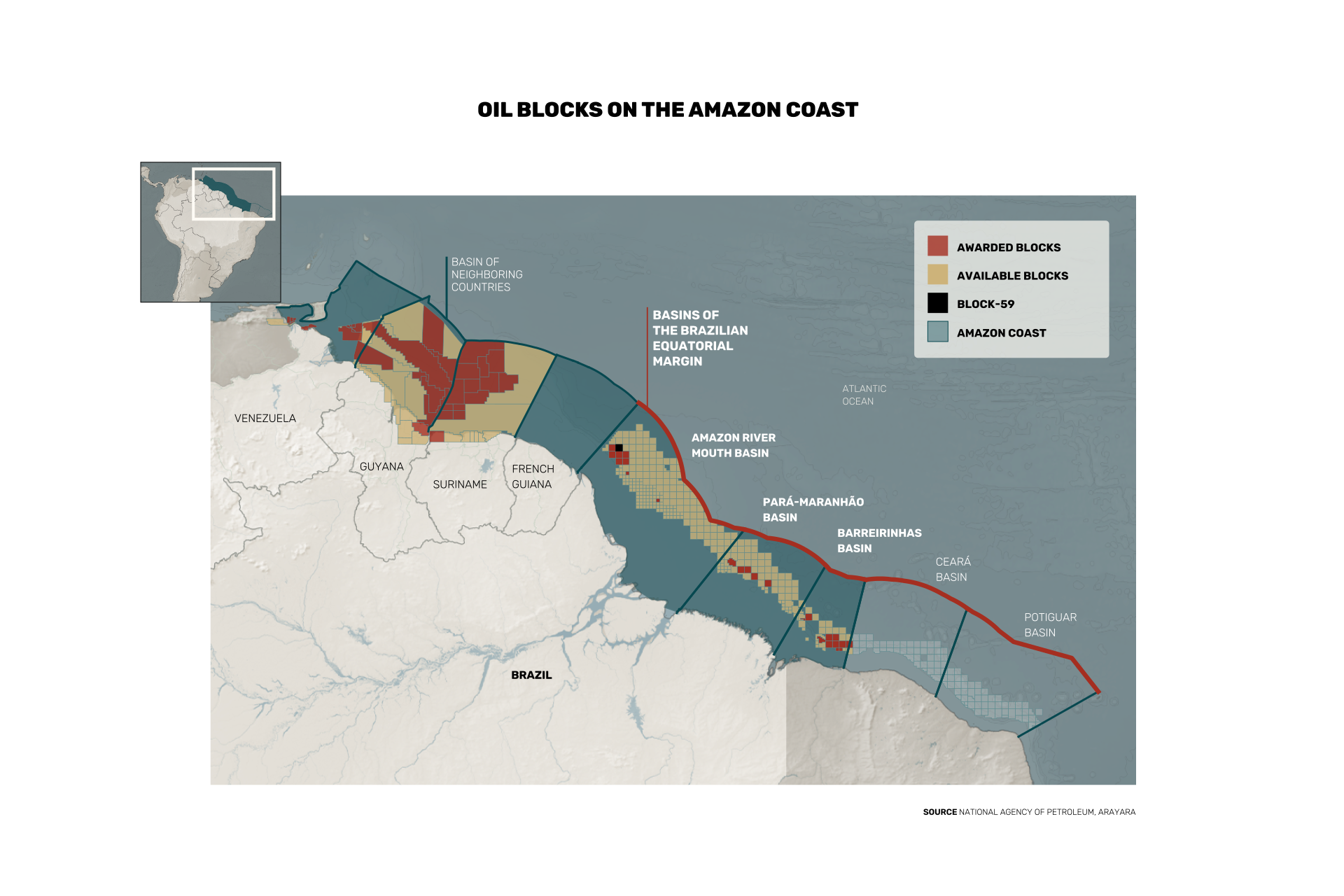

Almost 20 percent of global reserves identified between 2022 and 2024 are located in the region, primarily offshore along South America’s northern coast between Guyana and Suriname. This wealth has sparked increasing international interest from oil companies and neighbouring countries like Brazil, which is looking to exploit its own coastal resources.

In total, the Amazon region accounts for 5.3 billion barrels of oil equivalent (boe) of around 25 billion discovered worldwide during this period, according to Global Energy Monitor data, which tracks energy infrastructure development globally.

“The Amazon and adjacent offshore blocks account for a large share of the world’s recent oil and gas discoveries,” said Gregor Clark, lead of the Energy Portal for Latin America, an initiative of Global Energy Monitor. For him, however, this expansion is “inconsistent with international emissions targets and portends significant environmental and social consequences, both globally and locally.”

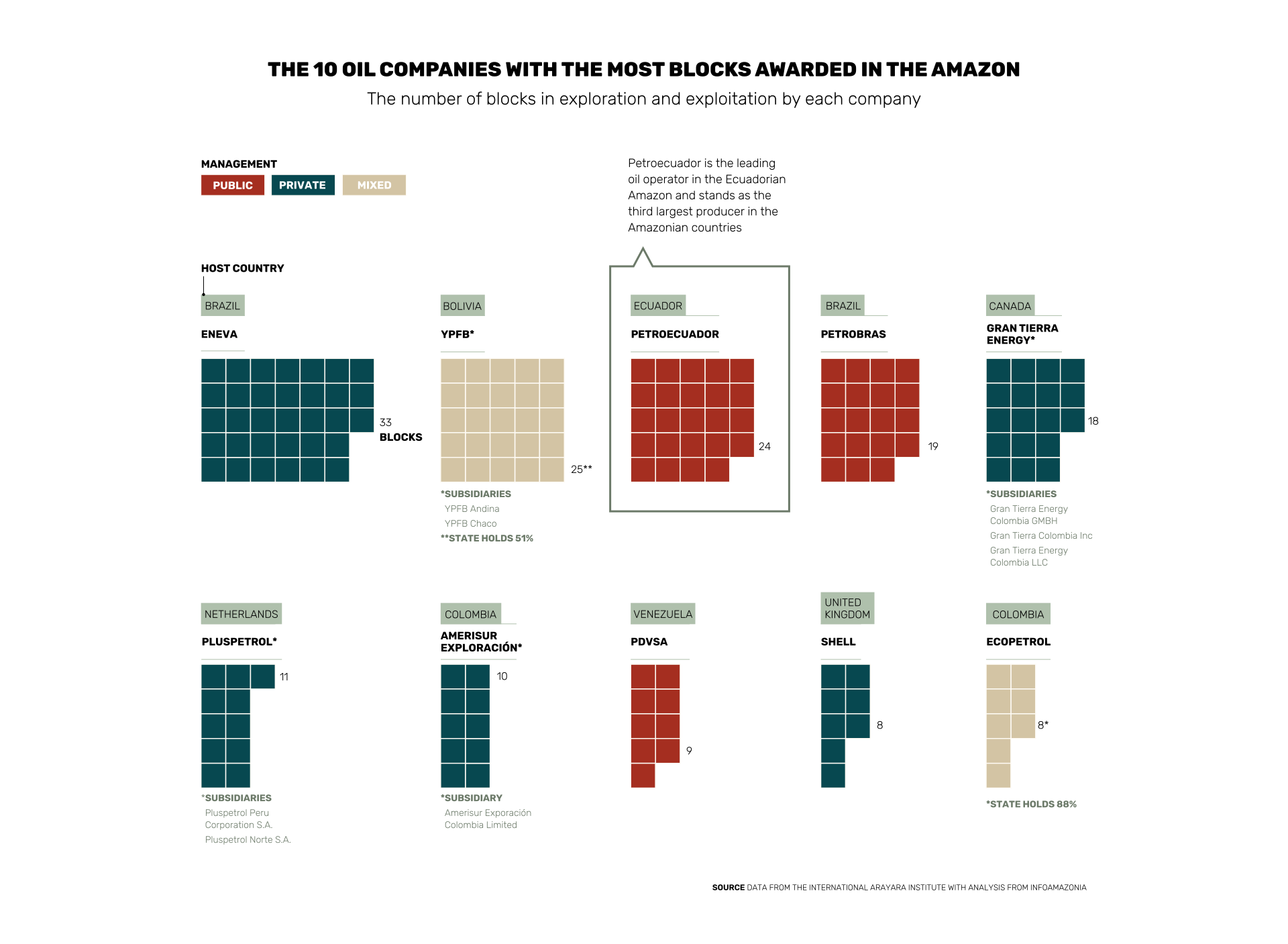

The region encompasses 794 oil and gas blocks – which are officially designated areas for exploration, though the existence of resources is not guaranteed. Nearly 70 percent of these Amazon blocks are either still under study or available for market bidding, meaning they remain unproductive.

In contrast, 60 percent of around 2,250 South American blocks outside the rainforest basin have already been awarded – authorized for reserve exploration and production – making the Amazon a promising avenue for further industry expansion, according to data from countries compiled by the Arayara International Institute up to July 2024. Of the entire Amazon territory, only French Guiana is devoid of oil blocks, as contracts have been banned by law there since 2017.

This new wave of oil exploration threatens a biome critical to the planet’s climate balance and the people who live there, coinciding with a global debate on reducing fossil fuel dependency.

“It’s no use talking about sustainable development if we keep exploiting oil,” said Guyanese Indigenous leader Mario Hastings. “We need real change that includes Indigenous communities and respects our rights.”

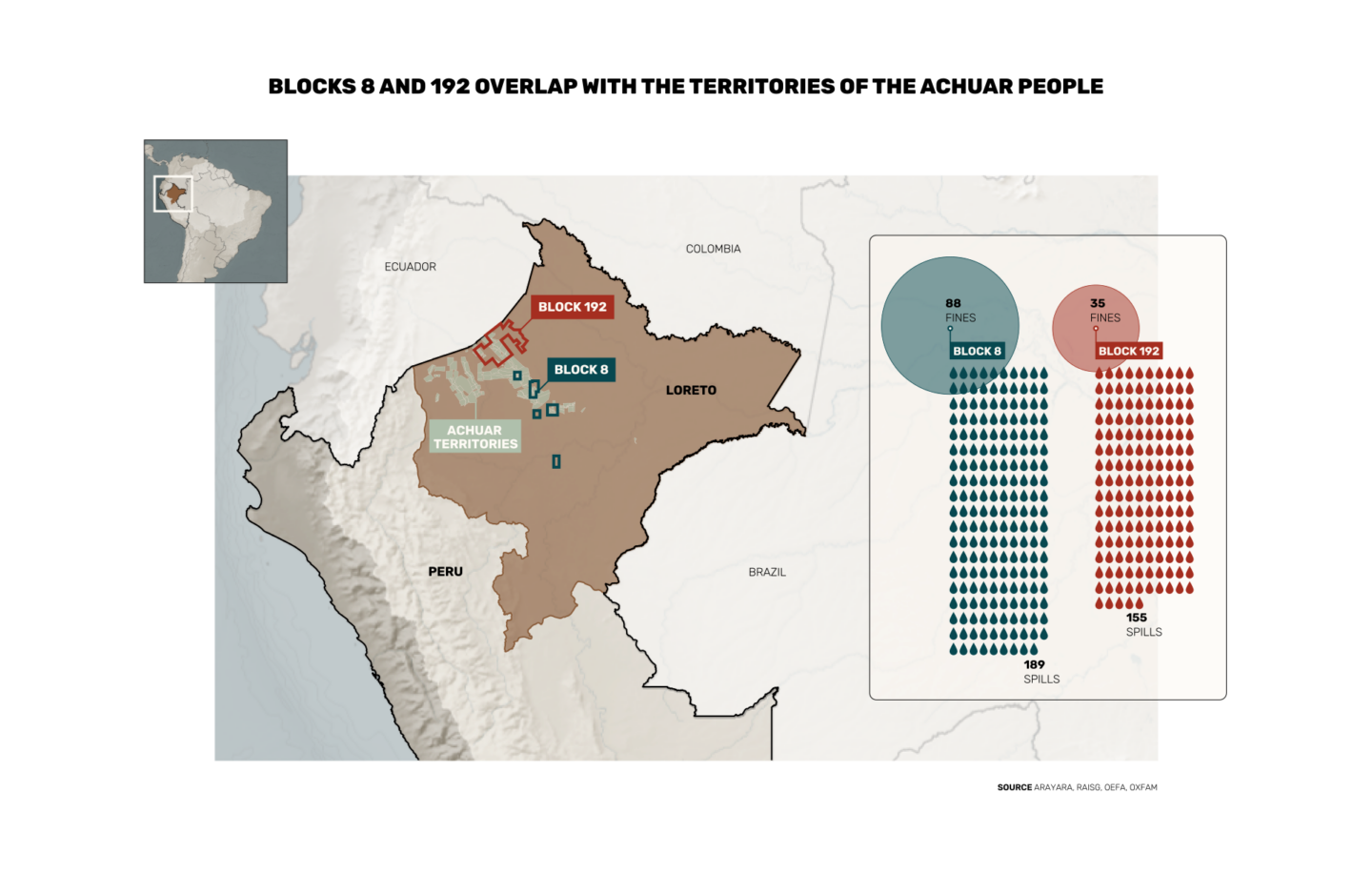

Across the eight Amazon countries analysed, 81 of all the awarded oil and gas blocks overlap with 441 ancestral lands, and 38 blocks were awarded within the limits of 61 protected natural areas. Hundreds of additional blocks are still under study or open for bids, the Arayara data shows.

Fossil fuel nations to see value of their economies shrink under new UN-agreed measure

Abundant in natural resources, the Amazon seldom benefits from their production. Instead, half of South America’s oil is exported to foreign markets, primarily to the United States and China, according to data from the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Royalties from the industry have exacerbated inequality rather than fostering local development, saddling the region with deforestation and water pollution from oil operations.

Meanwhile, Brazil will host more than 190 countries in the Amazon city of Belém later this year for the COP30 UN climate summit, which top diplomat André Aranha Corrêa do Lago has said will be “the first to undeniably take place at the epicentre of the climate crisis”, in an ecosystem on the verge of crossing an “irreversible tipping point”.

A new oil rush on the Amazon coast

Guyana, a small and hitherto inconspicuous nation in South America, has become the hotspot for global oil discoveries, earning the moniker “the new Dubai”, a designation often used by foreign executives at newly established companies in the country.

The oil boom has propelled Guyana’s economy forward, yet it also presents challenges such as rising inflation and worsening social inequality. Moreover, the burgeoning oil industry poses a threat to the country’s remarkable natural landscape, with 90 percent of Guyana still covered by the Amazon rainforest.

“The world is moving towards a future without fossil fuels, but Guyana is opening itself up to oil and gas,” said Guyanese environmentalist Sherlina Nagger. “Our leaders are on the wrong side of history.”

Recent substantial discoveries in neighboring Suriname, along with those in Guyana, have reignited interest in the “equatorial margin“. This coastal strip extends for thousands of kilometres near the equator and largely encompasses the Amazon biome.

Over 92 percent of the offshore blocks in the Amazon are either under study or available for market bidding, according to the project analysis.

Meanwhile, in the region, Venezuela has rekindled its interest in annexing Essequibo, a contested Guyanese territory. This area, once disputed by the Spanish and British empires in the 19th century, has again become a focus of attention due to its oil potential.

Meanwhile, Brazil, which is home to the largest portion of this strategic zone, faces obstacles to its oil exploration efforts. These include a history of unsuccessful drilling attempts dating back to the 1970s and, more recently, repeated refusals to allow state-owned oil company Petrobras to conduct research in Block 59. This area is situated in the Foz do Amazonas, where the mouth of Amazon River meets the Atlantic Ocean.

In May 2023, Ibama, Brazil’s environmental agency, denied Petrobras’ application to research the block. The agency’s report, endorsed by 26 analysts and reaffirmed in November 2024, highlighted flaws in the company’s emergency plans, which could endanger sensitive Amazonian ecosystems. This area has the largest continuous mangrove expanse in the world and a recently documented extensive reef system, both of which have significant scientific and ecological potential.

Such efforts to find fossil fuels in the region pose significant threats to the climate, researchers caution. “Opening up new areas for oil exploration in the Amazon contradicts the Paris Agreement’s recommendations to limit global warming,” warned Philip Fearnside, a scientist at the National Institute for Amazon Research. “Moreover, the risk of oil spills in this region would be catastrophic.”

Despite the risks, Petrobras remains undeterred in its pursuit of exploring the equatorial margin – and key figures in the Brazilian government have voiced their support for extraction. Finance minister Fernando Haddad preached “all caution” to ensure safe exploration, while Alexandre Silveira, minister of mines and energy, remarked that Guyana is “sucking the oil” from the region due to Brazil’s inaction.

“We’re going to explore the equatorial margin; there’s no reason not to,” President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva stated in a June 2024 interview.

Under political pressure, Marina Silva, Brazil’s minister for the environment and climate change, has reiterated that the decision made by Ibama, an agency under her ministry, is “technical”. She stressed the importance of adhering to the agency’s procedures to prevent “irreparable” environmental harm to the region.

Ecuador and Peru: a legacy of exploitation – and damage

Whereas oil exploration on the equatorial margin is just beginning, countries such as Ecuador, Peru, and Colombia have been producing oil in the Amazon for decades. While this activity has helped boost their economies, it has also deepened the damage to the biome.

In Ecuador, oil accounts for more than seven percent of the country’s GDP, but its production has resulted in an average of two oil spills a week in recent years. Since the 1970s, when the American company Texaco (now Chevron) opened the first major exploration frontier in the Ecuadorian Amazon, accidents have plagued the region.

Today, state-owned Petroecuador plays a leading role in the development of oil fields in the Ecuadorian Amazon. According to the project analysis, the state-owned enterprise oversees 24 oil and gas blocks. This is the largest number within Ecuador and ranks second among Amazon nations, after Brazilian natural gas company Eneva.

Among Petroecuador’s operations is the contentious Block 43 in Yasuní National Park, a sanctuary for one of the world’s most biodiverse regions and home to Indigenous peoples living in isolation. In August 2023, a historic referendum mandated the cessation of oil drilling in the park. The government was allowed one year to halt the activities; however, progress has been minimal, with efforts largely confined to forming a commission to oversee the measures sanctioned by the public vote.

“They are violating the most fundamental aspect of any democratic system: the will of the people expressed at the ballot box,” said Alex Rivas Toledo, an anthropologist and author of a book on the isolated peoples of the Yasuní.

To date, 21 blocks have been authorised within protected natural areas in the Ecuadorian Amazon, covering more than 7,000 square kilometres – the largest overlap among the countries analysed.

Of Ecuador’s 15 Indigenous nationalities, 11 reside in the Amazon region, where their way of life is often at odds with oil exploration efforts. The country has granted oil blocks that impact 207 Indigenous territories – the most among the countries analysed – covering nearly 21,000 square kilometres in the Amazon.

In Peru, which ranks second with nearly 14,000 square kilometres of oil blocks overlapping with 143 Indigenous lands, oil royalties have failed to improve the lives of local peoples, who grapple with poverty and limited access to essential services like healthcare.

Gas flaring affects Amazonians

In the Amazon, beyond the extraction of oil, gas flaring poses a significant concern. Seen from miles away, these intense flames blaze atop metal towers, discharging excess gas from oil exploration directly into the atmosphere. This process emits both carbon dioxide and methane, the latter causing 80 times more climate warming over short 20-year timescales.

Despite the harm this practice inflicts on the climate and human health, it is still permitted in some countries and is especially prevalent in remote areas like the Amazon, where inadequate infrastructure hampers the capture and processing of gas.

In 2023, Ecuador burned off 1.6 billion cubic metres of gas in oil operations in the Amazon, an amount more than triple the country’s total annual gas consumption, according to data analysis based on SkyTruth Flaring, a platform that employs satellite imagery to identify flaring.

Between 2012 and 2023, 17.6 billion cubic metres of gas were released in the Amazon. Ecuador was the predominant contributor, responsible for 75 percent of the total, equating to 34 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions released into the atmosphere.

“Catastrophic” acid spills at copper mines test Zambia’s plans to boost production

Ecuador is making internal efforts to address these emissions. In 2021, a regional court ordered the government to remove some of the oil industry’s gas flares located near populated areas in the Amazon provinces. However, this ruling has yet to be fully executed.

“We grew up alongside oil flares that, for more than half a century, have brought death, destruction, and poverty to our Amazon,” stated a group of young Amazonian women in a manifesto. Together with an organisation representing victims of the former Texaco, they are pursuing legal action to halt gas flaring in Ecuador.

Colombia’s energy transition faces obstacles

Since taking office in 2022, President Gustavo Petro has sought to steer Colombia in a different direction to other Amazonian nations by proposing environmentally ambitious policies. These include a ban on new oil and gas exploration, the cessation of fracking – a method involving the high-pressure injection of fluids to extract oil and gas which poses significant risks – and the suspension of offshore oil projects.

But Colombia faces a challenge with its existing 381 oil and gas contracts, which must be honoured, while the industry continues to push for research of new reserves.

Industry lobbyists claim that the nation has less than ten years’ worth of oil to meet domestic demands, which has fuelled exploration efforts. Between 2022 and 2023, Colombia ranked among the top ten countries in terms of discovered reserve volumes, according to Global Energy Monitor. Additionally, in 2024, Colombia’s state-owned Ecopetrol, along with Brazil’s Petrobras, uncovered new natural gas reserves in the country.

Luiz Afonso Rosário of climate campaign group 350.org Brasil said that, for decades, oil has been presented as a promise of economic liberation for South American countries. Yet, he stressed: “What we see is that all the social ills are there, and only half a dozen people have got rich.”

For Rosário, the chasm between promises and reality in the Amazon underscores an urgent need for a broader and more inclusive debate on the future of the biome. “They’re going to devastate the Amazon with more infrastructure to benefit the fossil industry. We should be investing in renewable energies,” he argued.

Additional reporting by Fábio Bispo, Isabela Ponce, Emilia Paz y Miño, Pilar Puentes and Aramís Castro