In April 2021, global banks and smaller lenders banded together in the world’s biggest climate finance coalition convened by the UK as host of the COP26 climate summit. A few short years later, a growing number have run for the exit, leaving the alliance in turmoil.

Members of the Net Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA) promised to progressively shift their investment dollars away from polluting industries and towards climate solutions such as renewable energy. They also pledged to set “science-based” goals for their businesses to reach net zero emissions no later than 2050.

UN special envoy and former central banker Mark Carney hailed the initiative – and its wider umbrella group called the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero – as the “breakthrough” in climate finance that the world needed to mobilise trillions of dollars in support of a low-carbon economy.

But, nearly four years on, with climate change-sceptic Donald Trump back in the White House, Wall Street banking giants have led an exodus from the coalition, emboldening some Canadian and Australian peers to follow suit.

Ending poverty and gangs: How Zambia seeks to cash in on the global drive for EVs

The flight of some of the NZBA’s most influential members risks further damaging the relevance of an initiative that has been facing questions over its real-world climate credentials for some time.

Planet-heating fossil fuels continue to attract close to $700 billion a year from global banks. A first large-scale assessment, published by the European Central Bank (ECB), last year showed that being a signatory to the voluntary alliance – and others like it – had made a negligible difference in advancing climate goals.

Today, with the NZBA facing a reputational crisis, its remaining 135 members and watchers of ESG efforts are sparring over its purpose and where it should head next.

“It is a matter of survival for the coalition,” Quentin Aubineau, a policy analyst at BankTrack, an NGO that monitors commercial banks’ activities, told Climate Home.

Trump effect

Last December, exactly one month after Trump’s election win, Goldman Sachs quit the Net Zero Banking Alliance, opening the floodgates. The other top five US banks – JPMorgan, Citigroup, Bank of America, Citigroup and Morgan Stanley – all left over the next month. Canada’s biggest lenders followed soon after, with Australia’s Macquarie being the latest out of the door.

While none of the banks gave an official reason for exiting the alliance, observers believe the move came in reaction to political pressure from Republican officials in the US – which is widely expected to ramp up under the new pro-fossil fuel administration.

In 2022, attorneys-general from 19 Republican-led states launched an investigation into whether leading US banks were colluding under the NZBA to “starve companies engaged in fossil fuel-related activities of credit”.

South Africa’s G20 push for local processing of transition minerals faces barriers

The campaign spread to Washington and, last December, a House committee dominated by Republicans said it had found “substantial evidence of collusion and anticompetitive behavior” by the financial industry to “impose radical ESG goals” on US companies.

“They [the banks] joined in a political context, and they are withdrawing in a political context,” said Brian O’Hanlon, managing director of the climate finance programme at RMI, a US-based think-tank that supports clean energy. RMI’s Center for Climate-Aligned Finance is a collaborating partner of the NZBA.

He added that in 2021, when the alliance was formed, the new administration under former President Joe Biden, a Democrat, put pressure on Wall Street institutions that were lagging behind their European peers on sustainability disclosures and climate finance.

The vicious cycle pushing Bangladeshi climate migrants into modern slavery

Under the NZBA, lenders voluntarily commit to aligning their operations with the global aim of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050, setting targets to help achieve the goal and documenting their progress every year.

O’Hanlon said most banks saw the coalition primarily as an avenue to agree on standardised guidelines for drafting net zero policies and now, having built their internal capacity, some see more risk than benefit in being part of the club.

The banks that quit the NZBA have so far kept their net zero targets, but their track record raises questions about their commitment to reducing emissions.

Limited real-world impact

Big US and Canadian banks remain the world’s largest financial supporters of fossil fuels, according to a report by green groups called “Banking on Climate Chaos”. Some like Goldman Sachs and Bank of America even increased their fossil-fuel deals after joining the coalition, Bloomberg reported.

“NZBA was mostly an excuse for these banks because they haven’t done anything concrete to switch their business towards low-carbon except setting targets but without adopting clear policies,” said Aubineau of BankTrack, which contributed to the report.

North American lenders are not alone in this. While the NZBA includes some progressive signatories that do explicitly rule out support for climate-polluting businesses, member banks featured in the “Banking on Climate Chaos” assessment provided around $253 billion to companies expanding fossil fuels in 2023.

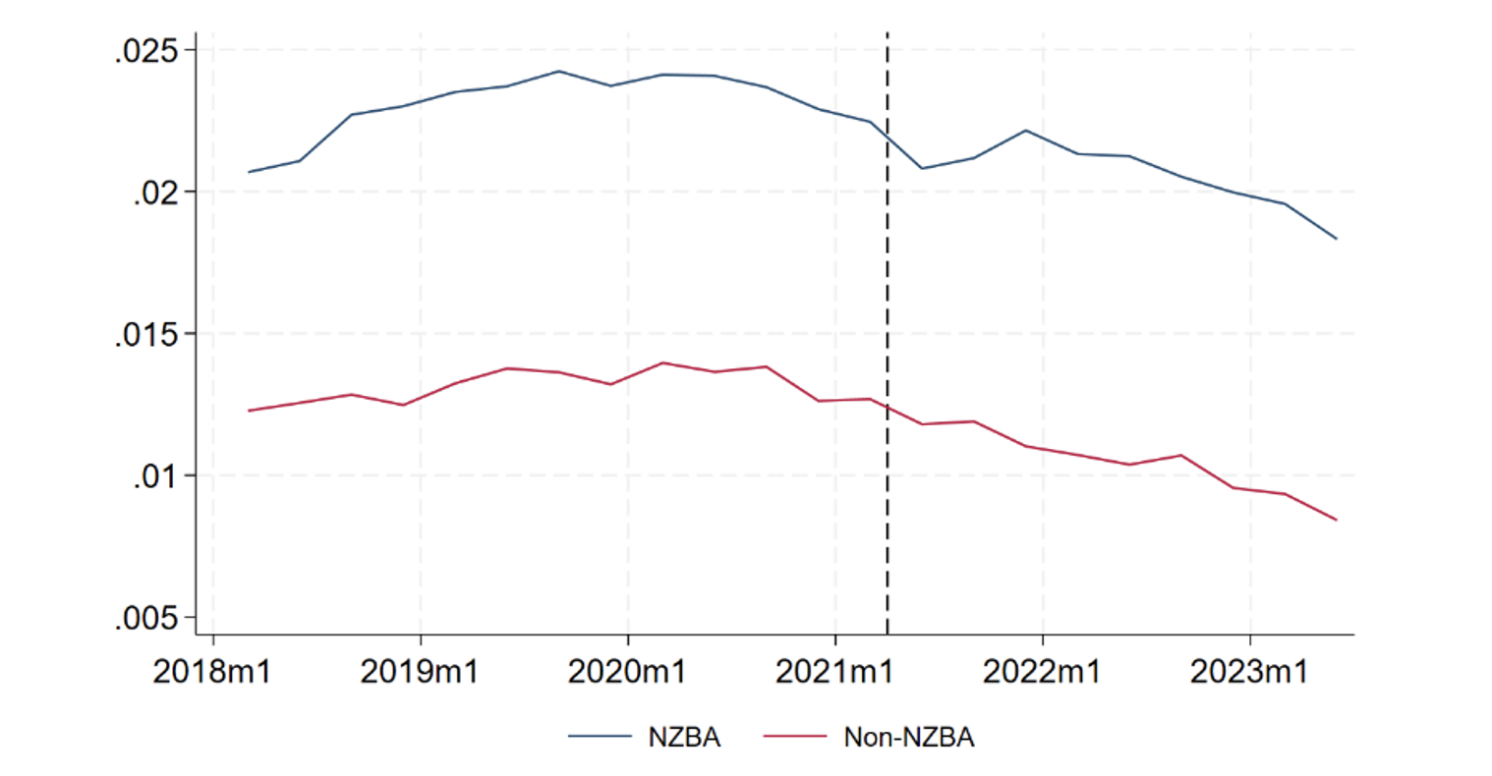

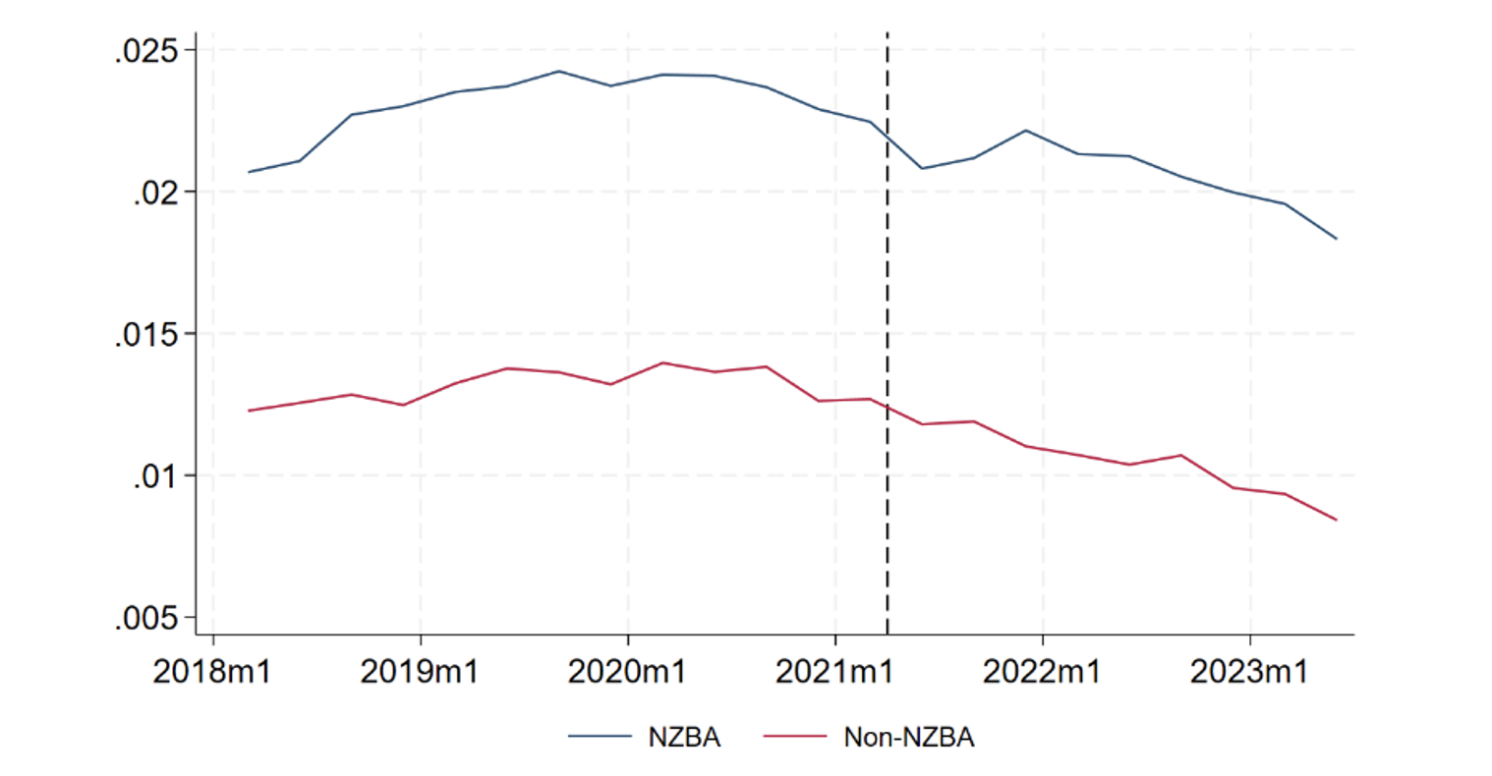

Meanwhile, for the ECB study, economists carried out a large-scale assessment of the lending behaviour of European banks and found virtually no difference between banks inside or outside of the coalition.

While European banks reduced their exposure to fossil fuels overall, NZBA members had neither divested from polluting companies nor engaged with them to push for emission-cutting measures any more than those without a climate commitment, according to the study.

“[The evidence] suggests that voluntary private-sector initiatives may have relatively little impact on decarbonization,” the authors concluded, calling on governments to improve the credibility of net zero promises in the private sector.

Expectation vs reality

The NZBA has been criticised repeatedly for a perceived failure to live up to its promise of fast-tracking a climate shift in finance.

BankTrack’s Aubineau said the NZBA leaves banks “a lot of room for manoeuvre” in how they set targets and communicate their actions, meaning “they can basically do whatever they want” with no accountability mechanism.

RMI’s O’Hanlon said the criticism is partly a consequence of the “inflated claims” made at the outset by the alliance which “raised expectations and obscured its meaning”.

“What GFANZ was doing in the first years was training for a race, but the rhetoric was that it was running the race and doing so with thoroughbred athletes,” he added.

Battle over NZBA’s future

Some of the NZBA’s remaining members, however, want to lead the pack and set a higher pace for transition. The Netherlands’ Triodos Bank and the UK’s Ecology Building Society threatened to quit the alliance in late 2023 over what they viewed as lax emissions reduction requirements.

But they eventually decided to stay, hoping to change the NZBA from the inside.

“By merely ‘encouraging’ disclosure of policies for the highest-emitting sectors, rather than requiring it, the [NZBA] guidelines undermine the transparency and action necessary to ensure safer climate outcomes,” they said in a letter written with the US-based Amalgamated Bank.

Following the US banks’ departure, the weight and make-up of the coalition have changed significantly. At its peak, the NZBA members had assets worth a combined $74 trillion – that is now down by a quarter. Meanwhile, European banks – which have so far stayed put – have gained greater influence.

Wall Street’s faltering on climate action opens up opportunity for European banks

Aubineau told Climate Home the internal debate over the future direction of the coalition is now picking up pace.

“The NZBA is trying to choose between two options: lower the ambition again and try to keep as many banks as possible or try to strengthen the guidance and move forward with those that are really committed,” he said.

While the departure of the US banks should be “a key opportunity” to turn a page and bolster commitments, “unfortunately, I think the NZBA might be considering the first option”, he warned.

HSBC – a founding member of the NZBA – ditched on Wednesday a target of reaching net-zero carbon emissions across its business by 2030 citing slow change in the real economy.

A decision over the direction of travel is expected in the next few months by the steering group, which includes both progressive lenders, including Amalgamated Bank, and some of the world’s top fossil fuel financiers, like Japan’s MUFG and Spain’s BBVA.

RMI’s O’Hanlon said that, while NZBA members should work out what the coalition is trying to achieve, climate regulations and government economic policy provide stronger transition levers than a voluntary framework.

“Incentives have always shaped the economic case for these financial institutions,” he added. “If the government tilts the market and the playing field to disadvantage certain technologies that are lower carbon, you will see a knock-on effect,” he added.