The world will need oil and gas for a few decades more, so who should produce it?

The Cop28 UN climate summit in December secured agreement from almost 200 nations to “transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems in a just, orderly and equitable manner” – a decision hailed by world leaders as “historic”.

But, while lots of countries are trying to reduce their use of planet-heating fossil fuels, only a handful have so far taken measures to produce less – particularly when it comes to oil and gas.

Last year, a United Nations report found that governments plan to produce more than double the amount of fossil fuels in 2030 than they should if global warming is to be limited to 1.5C. So they need to cut back.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) says no more new fossil fuel production projects are required, yet we will still need fossil fuels for the next few decades to keep economies running. That raises the question of who should get to drill, pump and sell those last supplies – and why?

Indonesia turns traditional Indigenous land into nickel industrial zone

Climate Home looked at three key criteria for the production of oil and gas. Unlike the other dirtiest fossil fuel – coal – they tend to be located together and so are produced in the same regions by the same nations. And the IEA predicts that their use will outlive that of coal.

We’ve looked at whose oil and gas is the cleanest, whose is the cheapest, and whose economy could most handle losing out on oil and gas revenue. Depending on the metric, the results differ wildly.

The cleanest oil and gas comes from Norway and the Arabian Gulf, the cheapest is in the Gulf. But when global economic justice is considered, the fairest is in smaller nations in the developing world – the likes of Libya, Trinidad and Tobago, and Turkmenistan.

Cleanest production?

Given the world will be using oil and gas for some time to come, shouldn’t we use that which causes the least damage to the planet?

While all oil and all gas is equally damaging to burn as fuel, the process of pumping it up from the ground can be more or less harmful to the climate.

Norway and the United Arab Emirates make this argument, arguing their oil and gas is the cleanest – and a November 2023 report by the IEA backs them up.

It found that Norway’s oil and its gas were the cleanest in the world to produce, measured by emissions intensity, while supplies from the UAE and other Gulf nations like Saudi Arabia and Qatar were also among the least damaging.

Norway’s oil and gas are cleaner because it has strict rules in place, requiring oil and gas producers to capture any methane gas that leaks during the production process. This prevents it from reaching the atmosphere and making climate change worse.

On top of this, much of the machinery used to produce the oil and gas doesn’t run on fossil fuels itself but on clean electricity.

A handful of Gulf states – including Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait and the UAE – have lower-intensity operations in part because of their “easy to access” reserves. As the oil is nearer the surface, less energy-guzzling machinery is needed to pump it up.

But the emissions from producing the oil and gas need to be put in perspective. It is the use of those fuels that has the biggest consequences. Just 5-20% of oil and gas companies’ total emissions are from production, according to energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie.

Cheapest energy?

Or should we use the cheapest oil and gas? The cheaper those fuels are to produce, the cheaper it should be to use our power plants, polyester and petrol. Those savings should be passed onto consumers around the world when they fill up their vehicles or switch on their lights.

This was an argument deployed by Amin Nasser, the head of oil giant Saudi Aramco, who told reporters at Davos in 2019: “There will continue to be growth in oil demand … We are the lowest-cost producer and the last barrel will come from the region.”

Gulf nations like Saudi Arabia again score well on this. As their oil and gas is near the surface, it’s cheaper to pump.

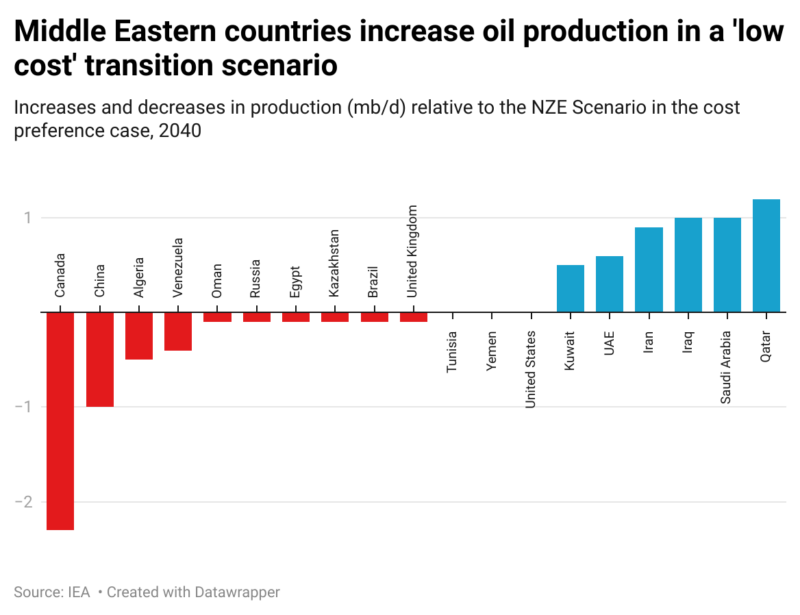

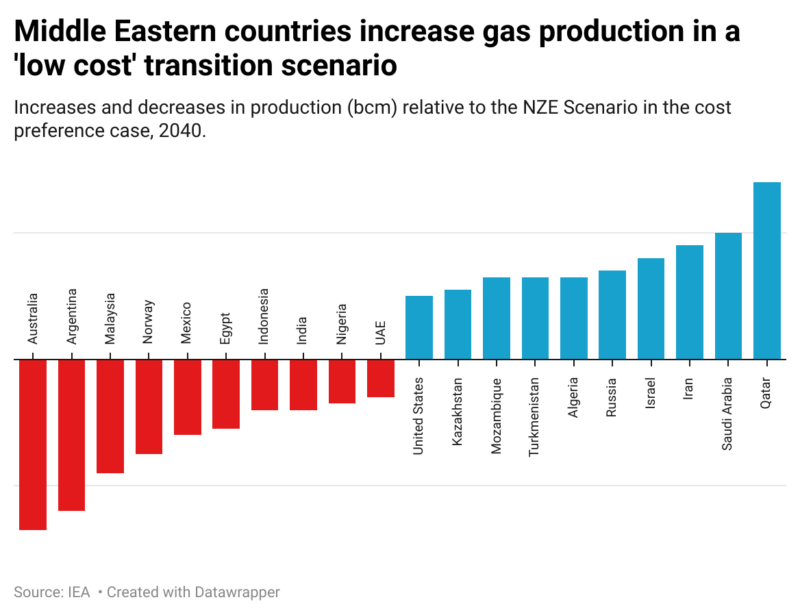

In the IEA’s “low cost” scenario, in 2040, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Iran increase their oil and gas production the most. More expensive producers like Canada, Australia and China have to cut down how much they pump.

Fairness and capacity?

Or should the governments that cut back on oil and gas output first be the historically large emitters that can most afford to go without the money they get from selling fossil fuels?

It’s an argument made by many African nations. Ahead of Cop28, African negotiators unsuccessfully proposed a ban on developed countries exploring for fossil fuels “well ahead of 2030, whilst affording developing countries the opportunity to close the global supply gap in the short term”.

Climate Analytics analyst Neil Grant argues we must take “capacity to transition” into account when thinking about who should be the last producers. A Carbon Tracker report found at least 28 oil and gas-reliant economies would lose half of their expected revenues under just a “moderate-paced transition” – so there is a lot at stake.

US trade agency backs oil and gas drilling in Bahrain despite Biden pledge

Greg Muttitt, from the International Institute of Sustainable Development, told Climate Home that if the transition is left to market forces, “a lot of people” in oil and gas-dependent economies will “get hurt”, either by losing their jobs, or experiencing a breakdown in public services.

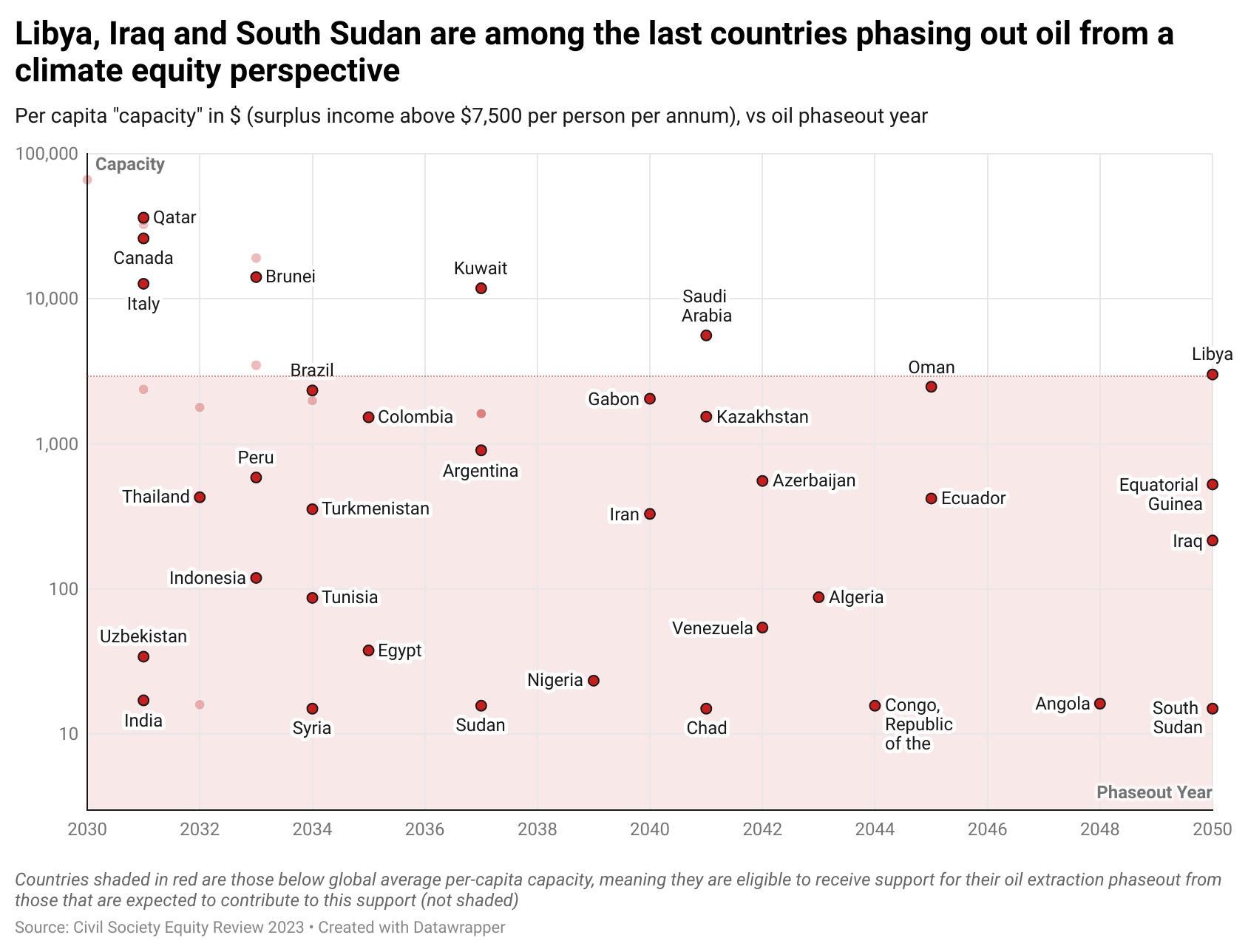

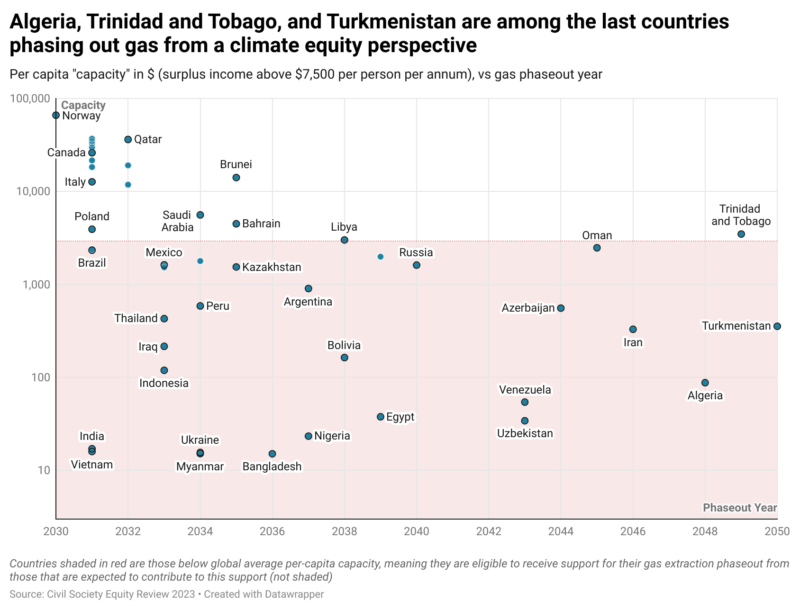

At Cop28, a network of civil society groups published a report assessing which countries should be the last to extract fossil fuels, accounting for both economic dependence, and climate equity.

Using a measure of financial “capacity”, defined as surplus income above “what is required to meet people’s needs”, the report found that Libya, Iraq and South Sudan should be among the last countries extracting oil, while Algeria, Trinidad and Tobago, and Turkmenistan are among the last extracting gas. The likes of Norway, Canada and Qatar should stop first for both, it concluded.

Whichever answer you chose, Michael Lazarus, co-author of the UN report and U.S. director for the Stockholm Environment Institute, told Climate Home he was pleased that “we have finally gotten to the point in the global conversation where folks are asking the question…of what that ultimate transition looks like.”