About seven years ago, Kristin and Josh Mohagen were honeymooning in Napa Valley in California, when they smelled something surprising in their glasses of Cabernet Sauvignon: green pepper. A vintner explained that the grapes in that bottle had ripened on a hillside alongside a field of green peppers. “That was my first experience with terroir,” Josh Mohagen says.

It made an impression. Inspired by their time in Napa, the Mohagens returned home to Fergus Falls, Minn., and launched a chocolate business based on the principle of terroir, often defined as “sense of place.”

Different countries produce cocoa with distinct flavors and aromas, Kristin Mohagen says. Cocoa from Madagascar “has a really bright berry flavor, maybe raspberry, maybe citrus,” she says, while cocoa from the Dominican Republic “has a little more nutty, chocolaty taste.”

The couple estimates that back in 2013, when they founded Terroir Chocolate, about 50 other small batch chocolate companies in the United States were also touting terroir as integral to their products’ flavors.

Since then, terroir has continued to take hold as a marketing strategy — and not just for wine and chocolate. Terroir labels are also becoming more common for products like coffee, tea and craft beer, says Miguel Gómez, an economist at Cornell University who studies food marketing and distribution. Consumers “are increasingly interested in knowing where the products they are eating are produced — not only where but who is making them and how,” he says. People “value differences in the aromas, the flavors.”

Hop plants grown in Washington’s Yakima Valley have a distinct chemical composition due to the soil, weather and how the plants grow.Nicholi J. Pitra and P.D. Matthews/Hopsteiner

Hop plants grown in Washington’s Yakima Valley have a distinct chemical composition due to the soil, weather and how the plants grow.Nicholi J. Pitra and P.D. Matthews/Hopsteiner

The definition of terroir is somewhat fluid. Wine enthusiasts use the French term to describe the environmental conditions in which a grape is grown that give a wine its unique flavor. The soil, climate and even the orientation of a hillside or the company of neighboring plants, insects and microbes play a role. Some experts expand terroir to include specific cultural practices for growing and processing grapes that could also influence flavor.

The notion of terroir is quite old. In the Middle Ages, Cistercian and Benedictine monks in Burgundy, France, divided the countryside into climats, according to subtle differences in the landscape that seemed to translate into unique wine characteristics. Wines produced around the village of Gevrey-Chambertin, for example, “are famous for being fuller-bodied, powerful and more tannic than most,” says sommelier Joe Quinn, wine director of The Red Hen, a restaurant in Washington, D.C. “In contrast, the wines from the village of Chambolle-Musigny, just a few miles south, are widely considered to be more fine, delicate and light-bodied.”

Some scientists and wine experts are skeptical that place actually leaves a lasting imprint on taste. But a recent wave of scientific research suggests that the environment and production practices can, in fact, impart a chemical or microbial signature so distinctive that scientists can use the signature to trace food back to its origin. And in some cases, these techniques are beginning to offer clues on how terroir can shape the aroma and flavor of food and drink.

What is terroir?

Scientists and food enthusiasts point to many components of place that may shape the aroma and flavor of food.

![]()

Climate: Including humidity level and minimum temperature

![]()

Sun exposure: How much light, and the time of day when sun is strongest

![]()

Soil: Is the plant set deep or shallow? Ratio of sand, silt and clay affects drainage

![]()

Food production: Drying cocoa beans in the sun or over a wood fire, for example

![]()

Topography: The elevation, slope, and orientation of a plant

![]()

Neighboring plants: Adjacent crops that compete for water or nutrients

![]()

Agricultural practices: Such as when and how vines are pruned and grapes are harvested

![]()

Insects: mites and aphids that eat hop plants and others

![]()

Microbes: The bacteria and yeast and other fungi on grapes

Coffee’s chemical fingerprint

Ecologist Jim Ehleringer of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City studies trace elements that plants passively take up. Those elements are a direct reflection of the soil. “Trace elements do not decay and so they become characteristic of a soil type and persist over time,” Ehleringer says.

To see if they could trace a coffee to its origin using the coffee’s blend of trace elements, Ehleringer and his team recently measured the concentrations of about 40 trace elements in more than four dozen samples of roasted arabica coffee beans from 21 countries. Roasting beans to different temperatures can affect the concentrations of individual elements. To correct for this roasting effect, Ehleringer calculated the ratio of each element to every other element in a sample, which remains fairly constant, even with roasting.

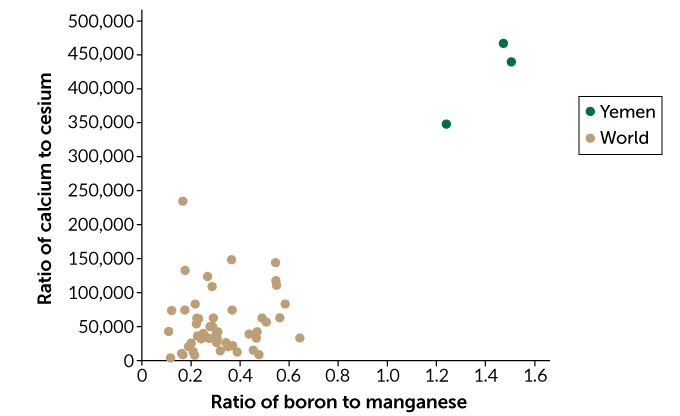

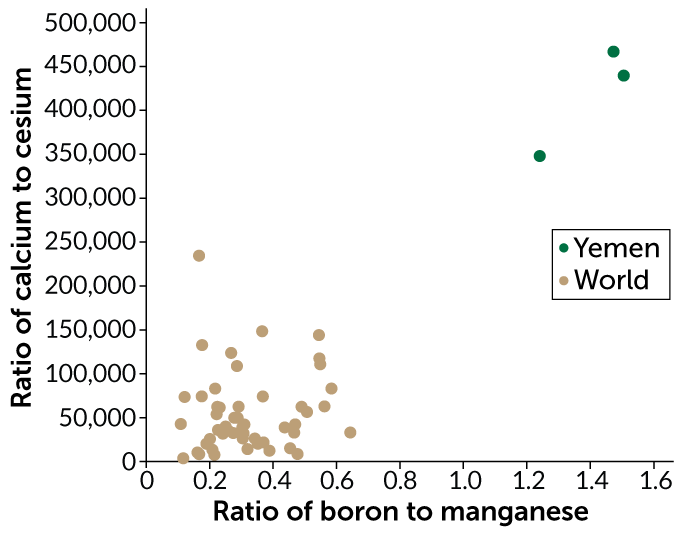

In the Aug. 1 issue of Food Chemistry, his team reports that coffee beans from different regions can have distinct chemical fingerprints. A coffee’s chemical quality “comes down to geology,” Ehleringer says. Three samples of coffee beans from Yemen, for example, had a ratio of boron to manganese that was shared by less than 0.5 percent of coffee samples grown elsewhere.

Trace differences

The ratios of trace elements boron to manganese and calcium to cesium are enough to distinguish Yemeni coffee beans from those grown in other parts of the world.

Trace elements set apart coffee beans  E. Otwell

E. Otwell  E. Otwell

E. Otwell

Source: N.Q. Bitter et al/Food Chemistry 2020

Other researchers have used similar elemental analyses to find chemical signatures of place in products ranging from wines produced in distinct growing regions in Portugal to peanuts grown in different provinces in China.

The technique is valuable for validating origin when terroir is part of a product’s allure. Coffee farmers in Kona on Hawaii’s Big Island, for example, are using the results of an elemental analysis to support a class action lawsuit, scheduled for trial in November, against 21 major retailers. The suit claims those companies falsely market their coffees as “Kona” when the beans were actually grown elsewhere.

While an elemental analysis can authenticate a product’s terroir, it does not suggest that geology shapes flavor. Trace elements alone, says Ehleringer, “impart no flavor or taste.”

Coffee beans, like those grown by farmers in Yemen, have distinct concentrations of trace elements, depending on where the beans were grown.Dmitry_Chulov/istock Editorial/Getty Images Plus

Coffee beans, like those grown by farmers in Yemen, have distinct concentrations of trace elements, depending on where the beans were grown.Dmitry_Chulov/istock Editorial/Getty Images Plus

Tracking cocoa to its source

To try to link flavor to place, some scientists go after different chemical signatures altogether. At Towson University in Maryland, chemist Shannon Stitzel is tracing cocoa to its roots using organic compounds, which are mostly produced by the cocoa plant itself. The concentration of specific organic compounds in a plant can result from a complex mix of interacting factors — from the genes of a particular variety to components of terroir like climate and agricultural practices.

Stitzel works with samples of cocoa liquor — cocoa beans that have been fermented, dried, roasted and ground into a paste — from across the globe. At room temperature, cocoa liquor is a solid. But with a bit of heat, the paste melts into a glossy liquid that Stitzel describes as “a little thicker than honey.”

Using organic compounds to assign the cocoa liquor samples to their countries of origin is “not nearly as clean as when you do it with elemental analysis,” she says. In unpublished work, she was able to use an elemental analysis to accurately link cocoa liquor to its country of origin about 97 percent of the time.

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.

Subscribe or Donate Now

But Stitzel turned to organic compounds because their presence may ultimately help explain the flavor differences that she, like the Mohagens, thinks very clearly exist between cocoa liquors from different countries. “You can open up each of the containers and the aroma is entirely different,” she says.

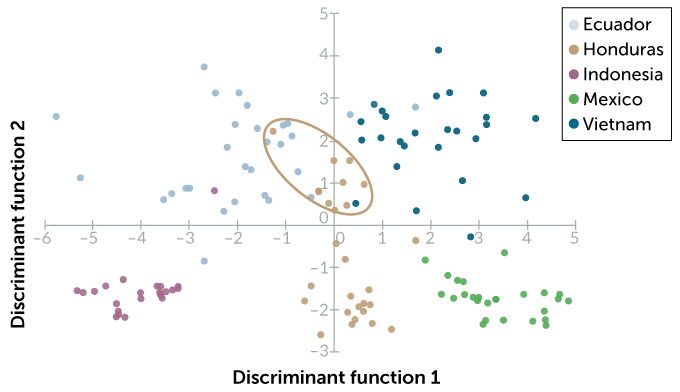

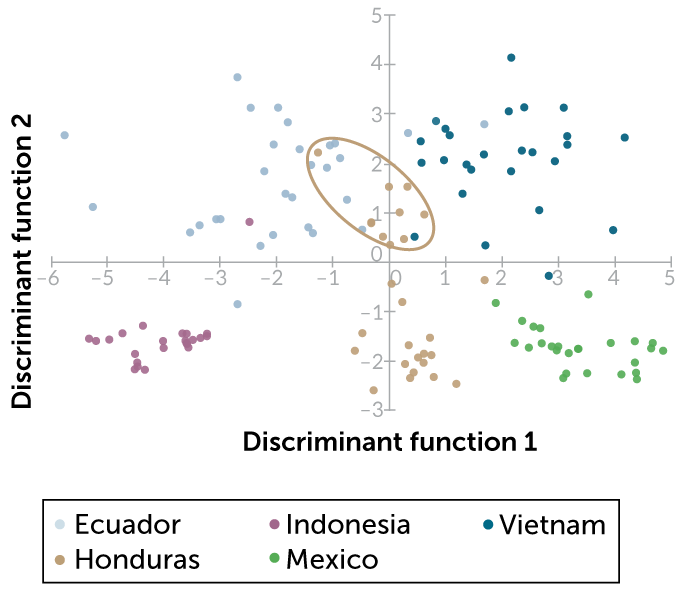

Stitzel recently identified concentrations of organic compounds in cocoa liquor from Vietnam, Indonesia, Honduras, Ecuador and Mexico. She then used a statistical technique known as a discriminant analysis to group samples based on similar concentrations of nine organic compounds, including caffeine, a similar compound called theobromine and an antioxidant called epicatechin.

On the American Chemical Society’s SciMeetings online platform in April, Stitzel reported that this chemical fingerprint was enough to accurately identify the correct country of origin for about 90 percent of the samples. In some cases, however, the samples didn’t form neat groups by country. Cocoa liquor samples from Honduras formed two different groups, depending on roasting temperature. Samples in the Honduras group that were roasted at the highest temperature were hard to tell apart from samples from Ecuador and Vietnam.

Stitzel now wants to add more compounds to the analysis to boost her sourcing accuracy and to connect regions to specific flavor compounds. “We’re still … trying to understand which compounds might be related to flavor,” she says. Her recent analysis already shows that caffeine, theobromine and epicatechin, which all produce a bitter flavor, can help set apart one country’s chocolates from another’s.

The roasting effect

Using a statistical technique known as a discriminant analysis, researchers grouped cocoa liquor samples according to similarities in the concentrations of nine organic compounds. Each country’s samples clustered together, except for those in the Honduras group that were roasted at the highest temperature; they overlapped (circled) with samples from Ecuador and Vietnam.

Analysis of organic compounds in cocoa liquor by country  G. Lembo et al/ACS Scimeetings 2020

G. Lembo et al/ACS Scimeetings 2020  G. Lembo et al/ACS Scimeetings 2020

G. Lembo et al/ACS Scimeetings 2020

The aroma of place

Other researchers are finding that terroir leaves an imprint on the molecules that shape food’s aroma. Plants produce compounds known as aroma glycosides, which contain a sugar component linked to a volatile aromatic compound. When intact, aroma glycosides have no scent. But breaking the sugar-volatile bond — via high temperatures, low pH or enzymes from yeast — sets the volatile and its aroma free. The bouquet of a nicely aged bottle of wine is made up, in part, of aroma volatiles in the grapes that yeast enzymes let loose over time.

Many beer brewers, however, would rather your IPA have the same reliable flavor whether you pop open the bottle this Friday or in October. When volatile aromatics let loose in a bottled beer, that’s no good for large-volume brewers who need to ship consistent-tasting products. Brewers call that volatile release “beer creep,” says Paul Matthews, a senior research scientist in the Washington state branch of Hopsteiner, an international commercial hop grower and processor headquartered in New York City.

If brewers add hops (the flower of the hop plant) to beer early in the brewing cycle, heat breaks the sugar-volatile bond and the aroma from aroma glycosides is largely lost before bottling. The remaining flavor is more consistent over time. But when craft brewers make “dry hopped” beers like IPAs, adding the hops after the boiling stage, this late addition allows many aroma glycosides to go into fermentation and then into the bottle intact. The compounds release volatile aromatics as yeast enzymes break bonds even after the bottle is capped. So the aromas of these beers are more likely to “creep” over time.

Because genetics influences aroma and flavor, Matthews is exploring whether it’s possible to better control aroma glycoside concentrations through breeding. Breeding hop varieties to have lower concentrations could diminish the “beer creep” problem faced by large-volume craft brewers who distribute their beer over long distances.

At the same time, Matthews and colleagues are investigating the potential of breeding hop varieties to have higher aroma glycoside concentrations for use by smaller craft brewers, who are less concerned about shelf life but want to enhance the aroma of their beers.

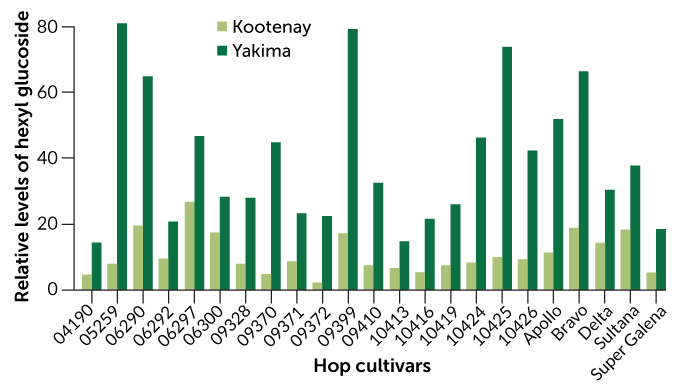

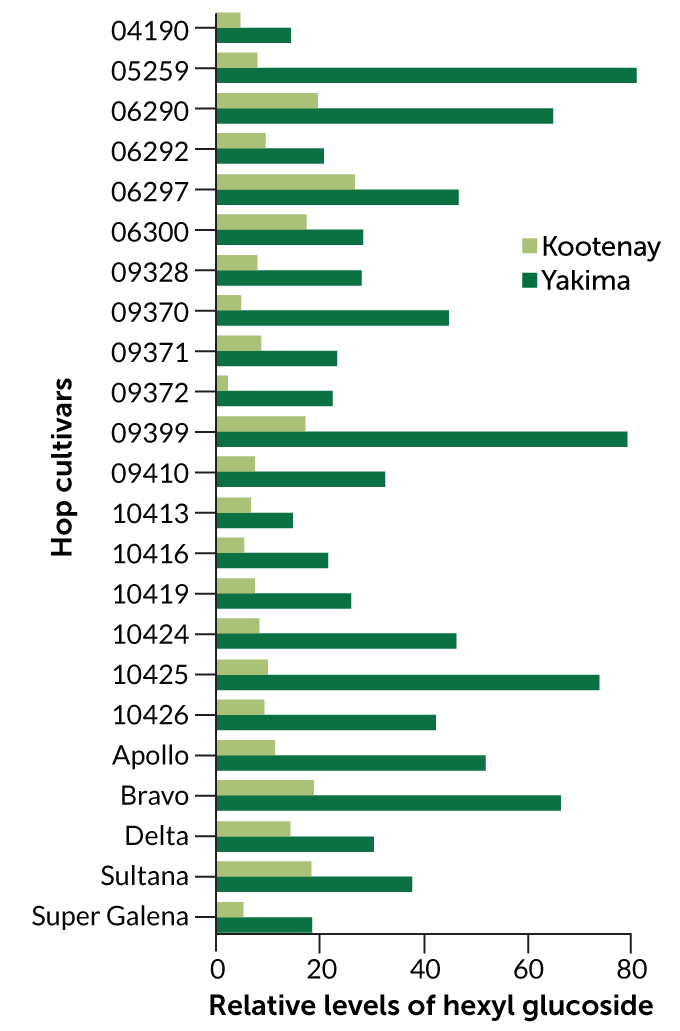

Levels of four aroma glycosides, which can give beer its distinct aroma, were compared in the same hop plant cultivars grown in Washington’s Yakima Valley (shown) and Idaho’s Kootenay River valley. One aroma glycoside stood out as different depending on where the plant grew.Nicholi J. Pitra and P.D. Matthews/Hopsteiner

Levels of four aroma glycosides, which can give beer its distinct aroma, were compared in the same hop plant cultivars grown in Washington’s Yakima Valley (shown) and Idaho’s Kootenay River valley. One aroma glycoside stood out as different depending on where the plant grew.Nicholi J. Pitra and P.D. Matthews/Hopsteiner

Matthews recently tested whether aroma glycoside concentrations in individual hop cultivars are determined more by genetics or by terroir. “Of course, they are determined by both,” he says. “But if they are more genetic, we can breed for them.”

In collaboration with colleagues, including phytochemist Taylan Morcol of Lehman College in the Bronx, part of the City University of New York, Matthews grew the same 23 genetically distinct hop cultivars at two commercial fields with distinct terroirs. Matthews calls the Yakima Valley site in Washington state “desert in the shadow of Mount Rainier.” The other site, in the Kootenay River valley in Idaho, is “much more boreal — pine forest and humid,” he says.

At each location, the team measured the concentrations of four aroma glycosides in each hop cultivar. Genetics indeed played the biggest role in determining how much aroma glycosides a hop plant produces, the researchers report in the Aug. 15 Food Chemistry. The concentrations of three of the aroma glycosides differed across cultivar types but remained fairly similar within the same cultivar grown in the two locations.

But for one aroma glycoside, terroir trumped genes in a big way. At the Kootenay site, all of the cultivars produced low concentrations of hexyl glucoside, a molecule that gives off a grassy aroma when its sugar bond is broken. But at the Yakima site, every one of these same cultivars, with genetics matching the plants in Kootenay, produced about two to eight times as much hexyl glucoside.

“There is a terroir difference,” Matthews says. The team can’t yet pinpoint which component of terroir causes the spike in hexyl glucoside at the Yakima site. The best guess: mites and aphids.

Terroir trumps genetics

Hop plant cultivars grown in Washington’s Yakima Valley produce higher levels of hexyl glucoside than the same cultivars grown in Idaho’s Kootenay River valley. The reason may be mites and aphids.

Growing location affects hexyl glucoside levels in hop  E. Otwell

E. Otwell  E. Otwell

E. Otwell

Source: T.B. Morcol et al/Food Chemistry 2020

At Yakima, those critters, which munch on the hop plants, hang around for a longer portion of the growing season than at the Kootenay site. Matthews and his colleagues hypothesize that the plants might produce hexyl glucoside chemicals as a defense against the pests. When a mite or aphid munches on the plant, the volatile may be released to attract insects that will eat the mites or aphids.

The researchers are planning a follow-up experiment to test whether hop plants exposed to these pests in environmentally controlled chambers produce more of this grassy hexyl glucoside than hop grown under the same environmentally controlled conditions without the pests.

Microbes leave their mark

People have understood the importance of yeast in wine fermentation for at least two centuries. About six years ago, food microbiologist David Mills of the University of California, Davis and graduate student Nicholas Bokulich, now a food microbiologist at ETH Zurich, discovered that groups of microbes may help shape the flavor of wine. Unique microbial communities in different California growing regions can predict which metabolites will be present in the finished wine, Mills, Bokulich and colleagues reported in 2016 in mBio. “Metabolites are any product of metabolism in any organism,” Bokulich says, adding that yeast, other fungi and bacteria each make varying contributions of metabolites in different wines.

“Those metabolites … have an aroma and a flavor,” says Kate Howell, a biochemist at the University of Melbourne in Australia. One of Howell’s own studies, she and her team reported online in August in mSphere, suggests that fungal species in particular shape the metabolites — and thus aroma and flavor — in wine from different growing regions in Australia.

Howell and colleagues studied microbes at 15 vineyards growing Pinot Noir grapes across six wine regions in southern Australia. At each vineyard, the team extracted fungal and bacterial DNA from the soil, as well as from what’s known as the “must” — destemmed, crushed grapes that haven’t yet been fermented. Then, the team identified 88 metabolites in the finished wine.

Different wine growing regions had distinct microbial communities in both the soil and the must, which appeared to influence the unique compositions of metabolites in the finished wine. The researchers found that over 80 percent of the metabolites found in the various wines were linked to the diversity of fungi found in the grape must. High levels of Penicillium fungi, for example, resulted in wine with low levels of octanoic acid, a volatile compound that can give wine a mushroom flavor.

Fungal distinctions

The diversity of yeast and other fungi found in grape must (the crushed grapes that haven’t yet been fermented) differs across distinct wine growing regions in southern Australia that produce Pinot Noir grapes. Researchers linked these fungal communities to distinct collections of metabolites that affect aroma and flavor in the finished wine.

Howell hopes vintners may someday be able to manage microbes in the soil and throughout the fermentation process to bring out the best of the local microbial terroir. Today, nearly all of the yeasts that vintners purchase to add to their grape must are isolated from French vineyards and other famous wine regions, she says. “That doesn’t present the same value of place as encouraging diversity in the fermentation in the place that the grapes were grown.”

For his part, Quinn, of The Red Hen, eagerly awaits more scientific explorations of terroir. He would especially like to know why wines produced from the limestone-dominated Kimmeridgian soils in Chablis, Sancerre and Champagne, France, all have a chalky, saltlike mineral taste. Scientific research helps explain how wine reflects its place, Quinn says, “from the climatic elements to the microbial elements, what the earth is saying, and why [a particular] wine is so delicious.”