“The Tale of Genji,” often called Japan’s first novel, was written 1,000 years ago. Yet it still occupies a powerful place in the Japanese imagination. A popular TV drama, “Dear Radiance” – “Hikaru kimi e” – is based on the life of its author, Murasaki Shikibu: the lady-in-waiting whose experiences at court inspired the refined world of “Genji.”

Romantic relationships, poetry and political intrigue provide most of the novel’s action. Yet illness plays an important role in several crucial moments, most famously when one of the main character’s lovers, Yūgao, falls ill and passes away, killed by what appears to be a powerful spirit – as later happens to his wife, Aoi, as well.

Someone reading “The Tale of Genji” at the time it was written would have found this realistic – as would some people in different cultures around the world today. Records from early medieval Japan document numerous descriptions of spirit possession, usually blamed on spirits of the dead. As has been true in many times and places, physical and spiritual health were seen as intertwined.

As a historian of premodern Japan, I’ve studied the processes its healing experts used to deal with possessions, and illness generally. Both literature and historical records demonstrate that the boundaries between what are often called “religion” and “medicine” were indistinct, if they existed at all.

Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Vanquishing spirits

The government department in charge of divination, the Bureau of Yin and Yang, established in the late seventh century, played a crucial role. Its technicians, known as onmyōji – yin and yang masters – were in charge of divination and fortunetelling. They were also responsible for observing the skies, interpreting omens, calendrical calculations, timekeeping and eventually a variety of rituals.

Today, onmyōji appear as wizardlike figures in novels, manga, anime and video games. Though heavily fictionalized, there is a historical kernel of truth in these fantastical depictions.

Starting from around the 10th century, Onmyōji were charged with carrying out iatromancy: divining the cause of a disease. Generally, they distinguished between disease caused by external or internal factors, though boundaries between the categories were often blurred. External factors could include local deities known as “kami,” other kami-like entities the patient had upset, minor Buddhist deities or malicious spirits – often revengeful ghosts.

In the case of spirit-induced illness, Buddhist monks would work to winnow out the culprit. Monks who specialized in exorcistic practices were known as “genja” and were believed to know how to expel the spirit from a patient’s body through powerful incantations. Genja would then transfer it onto another person and force the spirit to reveal its identity before vanquishing it.

Heritage Images/Hulton Archive via Getty Images

Court physicians

While less common than spirit possessions, the idea that physical factors could also cause illness appears in sources from this period.

Since the late seventh century, the government of the Japanese archipelago had established a bureau in charge of the well-being of aristocratic families and high-ranking members of the state bureaucracy. This Bureau of Medications, the Ten’yakuryō, was based on similar systems in China’s Tang dynasty, which Japanese officials adapted for their own culture.

The bureau’s members, whom scholars today often call “court physicians” in English, created medicinal concoctions. But the bureau also included technicians tasked with using spells, perhaps to protect high-ranking people from maladies.

Not either/or

Some scholars, both Japanese and non-Japanese, compare the practices of members of the Bureau of Medications with what is now called “traditional Chinese medicine,” or just “medicine.” They typically consider the onmyōji and Buddhist monks, meanwhile, to fall under the label of “religion” – or perhaps, in the case of onmyōji, “magic.”

But I have found numerous signs that these categories do not help people today make sense of early medieval Japan.

Starting in the seventh century, as a centralized Japanese state began to take shape, Buddhist monks from the Korean Peninsula and present-day China brought healing practices to Japan. These techniques, such as herbalism – treatments made of plants – later became associated with court physicians. At the same time, though, monks also employed healing practices rooted in Buddhist rituals. Clearly, the distinction between ritual and physical healing was not part of their mindset.

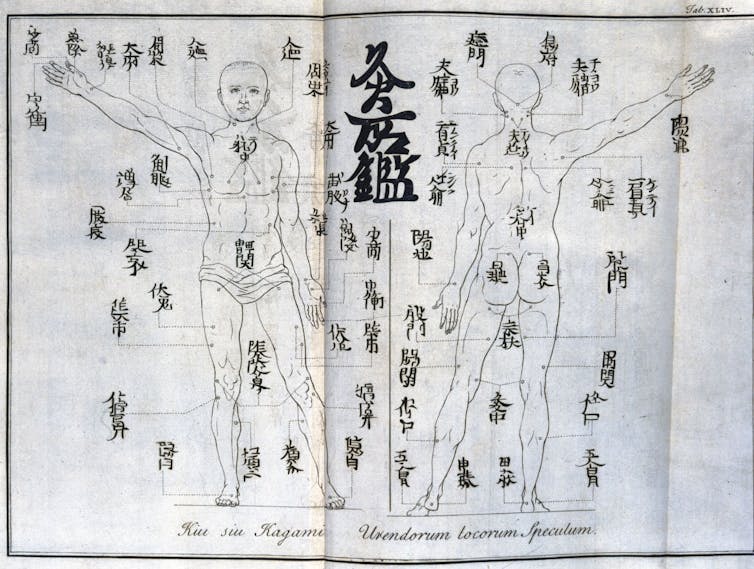

Similarly, with court physicians, it is true that sources from this period mostly show them practicing herbalism. Later on, they incorporated simple needle surgeries and moxibustion, which involves burning a substance derived from dried leaves from the mugwort plant near the patient’s skin.

Science & Society Picture Library via Getty Images

However, they also incorporated ritual elements from various Chinese traditions: spells, divination, fortunetelling and hemerology, the practice of identifying auspicious and inauspicious days for specific events. For example, moxibustion was supposed to be avoided on certain days because of the position of a deity, known as “jinshin,” believed to reside and move inside the human body. Practicing moxibustion on the body part where “jinshin” resided in a specific moment could kill it, therefore potentially harming the patient.

Court physicians were also expected to ritually “rent” a place for a pregnant woman to deliver, producing talismans written in red ink that were meant to function as “leases” for the birthing area. This was done in order to keep away deities who might otherwise enter that space, possibly because childbirth was believed to be a source of defilement. They also used hemerology to determine where the birthing bed should be placed.

In short, these healing experts straddled the boundaries between what are often called “religion” and “medicine.” We take for granted the categories that shape our understanding of the world around us, but they are the result of complex historical processes – and look different in every time and place.

Reading works like “The Tale of Genji” is not only a way to immerse ourselves in the world of a medieval court, one where spirits roam freely, but a chance to see other ways of sorting human experience at work.