A new type of gene therapy that rewires nerve cells in the eye has given a blind man some limited vision.

The 58-year-old man has a genetic disease called retinitis pigmentosa, which causes light-gathering cells in the retina to die. Before the treatment, known as optogenetic therapy, the man could detect some light but couldn’t see motion or pick out objects. Now he can see and count objects and even reported being able to see the white stripes of a pedestrian crosswalk, researchers report May 24 in Nature Medicine. His vision is still limited and requires him to wear special goggles that send pulses of light to the treated eye.

“It’s exciting. It’s really good to see it working and getting some definite responses from patients,” says David Birch, a retinal degeneration expert at the Retina Foundation of the Southwest in Dallas. Birch has conducted clinical trials of other optogenetic therapies, but was not involved in this study.

A man who has a degenerative eye disease is able to detect light, but can’t usually pick out objects. After optogenetic therapy and months of training with special goggles that send pulses of light to his treated eye, he was able to see a book and bottle of hand sanitizer on a table.

Researchers have been working for more than a decade on optogenetic therapies to restore vision to people with degenerative eye diseases, such as retinitis pigmentosa (SN: 5/15/15). The therapy involves using a light-sensitive protein to make nerve cells fire off a signal to the brain when hit with a certain wavelength of light.

Optogenetic therapy is different from traditional gene therapy, which replaces a faulty version of a gene with a healthy one. It is also different from gene editing, which uses molecular tools such as CRISPR/Cas9 to fix disease-causing variants in particular genes. In 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a traditional gene therapy that treats a rare forms of inherited blindness caused by mutations in the RPE65 gene. And other researchers are doing clinical trials of gene editing to correct one particular mutation that causes an inherited form of blindness called Leber congenital amaurosis 10 (SN: 8/14/19).

Those therapies may halt or slow progression of degenerative eye diseases, but don’t help people who have already lost vision, says Botond Roska, a neuroscientist and gene therapist at the Institute of Molecular and Clinical Ophthalmology Basel and the University of Basel in Switzerland. Gene therapy and gene editing also target only certain genes, but retinitis pigmentosa can be caused by changes in any one of more than 50 genes. Optogenetic therapy may help people who have lost their sight from many diseases regardless of the gene changes that cause them. Such diseases potentially include macular degeneration, which affects millions of people worldwide.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Earlier versions of optogenetic therapy used a protein called channelrhodopsin-2 from algae to make nerve cells respond to light. That protein requires lots of bright blue light to make it work. “It’s like staring at the sun in the desert,” says José-Alain Sahel, an ophthalmologist and retina specialist at the University of Pittsburgh and Sorbonne University in Paris. The level of light needed to turn the protein on could kill any remaining cells in the retina. So Sahel, Roska and colleagues developed their therapy using a different light-sensing protein that responds to amber light, which does less damage to cells than blue or green wavelengths.

The team used a virus called an adeno-associated virus to deliver instructions for making the protein to certain cells in the man’s eyes. The team chose to insert the instructions in a layer of nerve cells called ganglion cells.

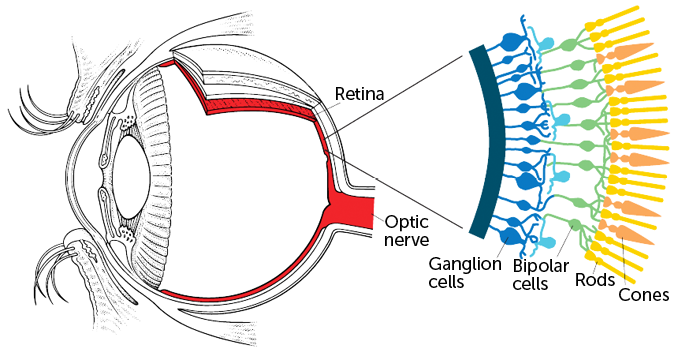

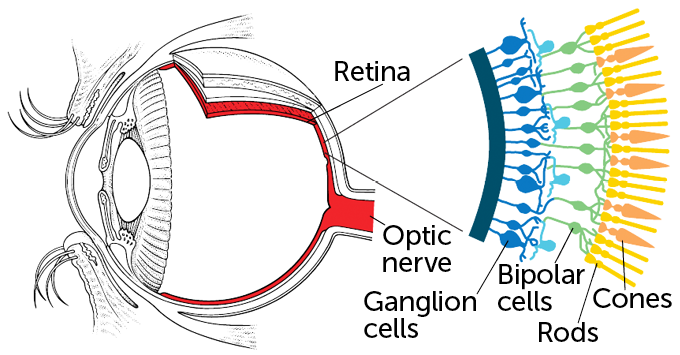

The retina has three layers: Light-gathering rods and cones are at the back of the retina. Those photoreceptor cells are the first to die in the degenerative disease. Next comes a layer of nerve cells known as bipolar cells. They process visual information and pass signals on to ganglion cells in the third layer. The ganglion cells fire messages to visual centers in the brain.

Seeing the light

The retina is a multilayered tissue at the back of the eye. Light-detecting rods and cones sit at the very back of the tissue. Those photoreceptor cells pass information to the brain via bipolar cells and ganglion cells. Inherited blindness conditions and degenerative eye diseases can kill photoreceptors or strip them of their light-detecting parts. The remaining bipolar cells and ganglion cells stick around longer, making those cells prime targets for optogenetic therapy. Researchers have now inserted a protein that senses amber light into ganglion cells of a man with retinitis pigmentosa, restoring some vision.

EYE: TONY GRAHAM/GETTY IMAGES, ADAPTED BY J. HIRSHFELD; WEBVISION.MED.UTAH.EDU, ADAPTED BY J. HIRSHFELD

EYE: TONY GRAHAM/GETTY IMAGES, ADAPTED BY J. HIRSHFELD; WEBVISION.MED.UTAH.EDU, ADAPTED BY J. HIRSHFELD  EYE: TONY GRAHAM/GETTY IMAGES, ADAPTED BY J. HIRSHFELD; WEBVISION.MED.UTAH.EDU, ADAPTED BY J. HIRSHFELD

EYE: TONY GRAHAM/GETTY IMAGES, ADAPTED BY J. HIRSHFELD; WEBVISION.MED.UTAH.EDU, ADAPTED BY J. HIRSHFELD

Some researchers, including Sahel and Roska’s team, are also experimenting with inserting optogenetic proteins into bipolar cells, dormant cones (ones that have lost function but haven’t died) or other nerve cells. But ganglion cells were the easiest target, Roska says. They can be reached by simply injecting the virus into the center of the eye. And ganglion cells stick around long after rods, cones and bipolar cells have died.

The French man still cannot see without special goggles that send pulses of amber light to his eye. That is because ganglion cells usually respond to changes in light. If the light is constant, they don’t continue to fire, so pulses are needed, Roska says.

In addition, while normal vision can work in dim starlight to the sunniest day on the beach, the optogenetic proteins have a very limited range of light levels that they can operate under, says Zhuo-Hua Pan, a vision neuroscientist at Wayne State University in Detroit not involved in the research. The goggles use digital camera technology to automatically adjust light levels to send to the man’s eye. People who get optogenetic therapy might all need to wear goggles to help process visual information before it goes to the brain, Pan and Birch say.

With the goggles sending pulses of light to his treated eye, the man could see and recognize objects such as a book, cups and a bottle of hand sanitizer on a table.

The researchers demonstrate that the goggles are necessary for the man to see the objects. To really show the therapy worked, the researchers would need to see if shining the amber light into his eye before the therapy could be enough to allow him to see, says Sheila Nirenberg, a neuroscientist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City and founder of Bionic Sight, a company that is also using optogenetics to treat blindness. If so, that would suggest that just bright light, not the therapy itself, is behind the change in vision.

Her company reported in a news release in March that blind people in its clinical trial could see light and motion after treatment. The results are preliminary. A full report from the clinical trial may be a year or more away, Nirenberg says.

Another company, Nanoscope Technologies in Bedford, Texas, said in a presentation at a virtual meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology in November that it had also restored limited vision to some people with retinitis pigmentosa. But a full accounting of the data hasn’t been released. “Without the details it’s difficult to evaluate,” says Pan.

The Nature Medicine report is encouraging because it shows some of those details, although Pan says he wants to know more about what the patient can see outside of the lab. Still, he says he’s pleased that the work is finally yielding results. “We’ve been waiting to hear this for many years.”

Sahel and Roska stress that the therapy is not a cure for blindness. “For now, all we can say is that there is one patient … with a functional difference,” Roska says. Sahel adds, “it’s a milestone on the road to even better outcomes.”