Anti-GMO activists in one county in California complained so much about glyphosate (Part 2 in this series addresses glyphosate; read the GLP’s GMO FAQ backgrounder on glyphosate for an extensive analysis of its potential health dangers) that the county switched to organic alternatives , but the alternatives required gardeners to use body suits and respirators during application because the organic substitutes caused eye irritation and respiratory problems. The alternatives were also less effective as glyphosate. And they were as much as sixteen times as expensive.

The inherent restrictions required in organic farming result in organic farmers sometimes having to use more toxic pesticides and less environmentally-friendly technology and farming practices.

5: Soil health―When synthetic pesticides are more sustainable than ‘natural’ organics

Tillage is one example of organic farming being less sustainable than conventional farming. Tillage is a technique farmers use to prepare soil for a crop. It involves digging, stirring and overturning the soil. Tillage helps make it easier to plant crops and destroy weeds.

However, tillage breaks down soil structure, significantly increases erosion, causes the soil to lose nutrients, reduces biodiversity of insects and animals in the soil and releases greenhouse gas into the atmosphere. It is definitely not the most sustainable farming practice. Conventional agriculture has more options to avoid tillage, and some GMO crops aid with no-till weed control, while organic agriculture still has to rely at least in part on tillage, even at the expense of sustainability.

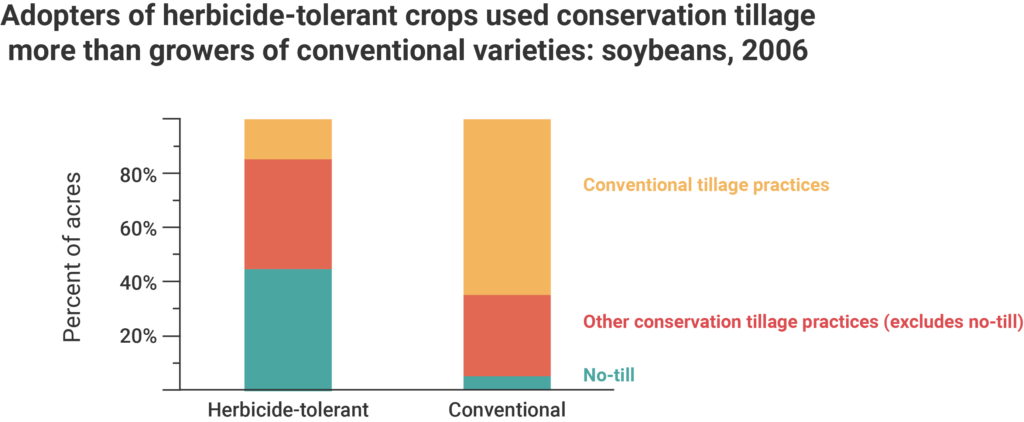

Conventional agriculture can use herbicide-tolerant crops. These are crops that have been genetically engineered to tolerate specific herbicides, like glyphosate. The graph below shows that when using herbicide-tolerant crops, farmers do not need to rely on tillage as much as conventional farmers (data from the USDA Economic Research Service using data from the 2006 ARMS Phase II soybean survey). However, genetically engineered crops are by definition not available to organic farmers. Therefore, it has been more difficult for organic farmers to adopt no-till farming practices.

The restrictions on organic farming, with the focus on being “natural,” do not allow for some modern improvements that could help increase sustainability, including the reduced use of tilling. While there is some adoption of a roller crimper for organic no-till, the adoption has been an uphill climb, failing to scale:

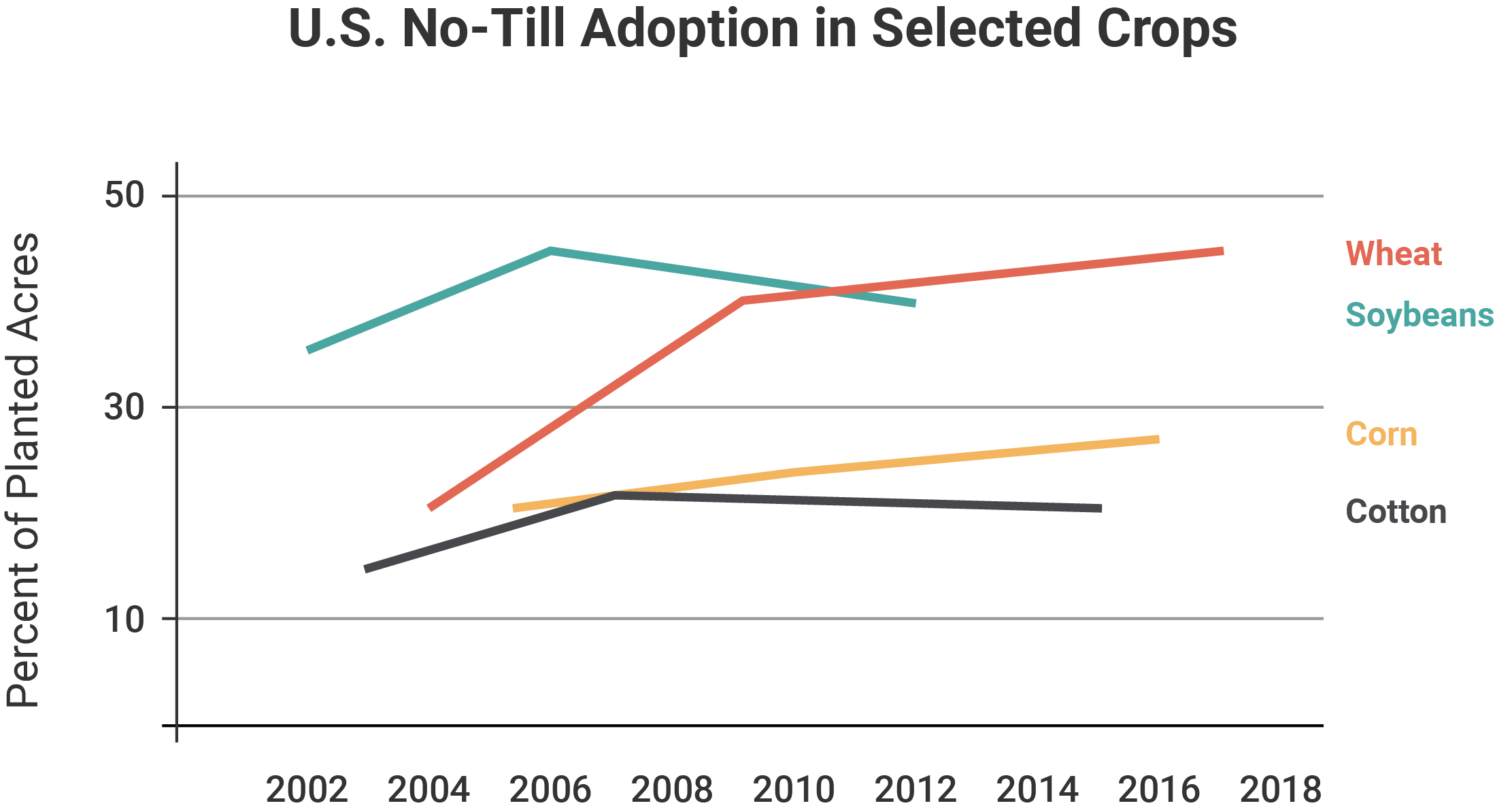

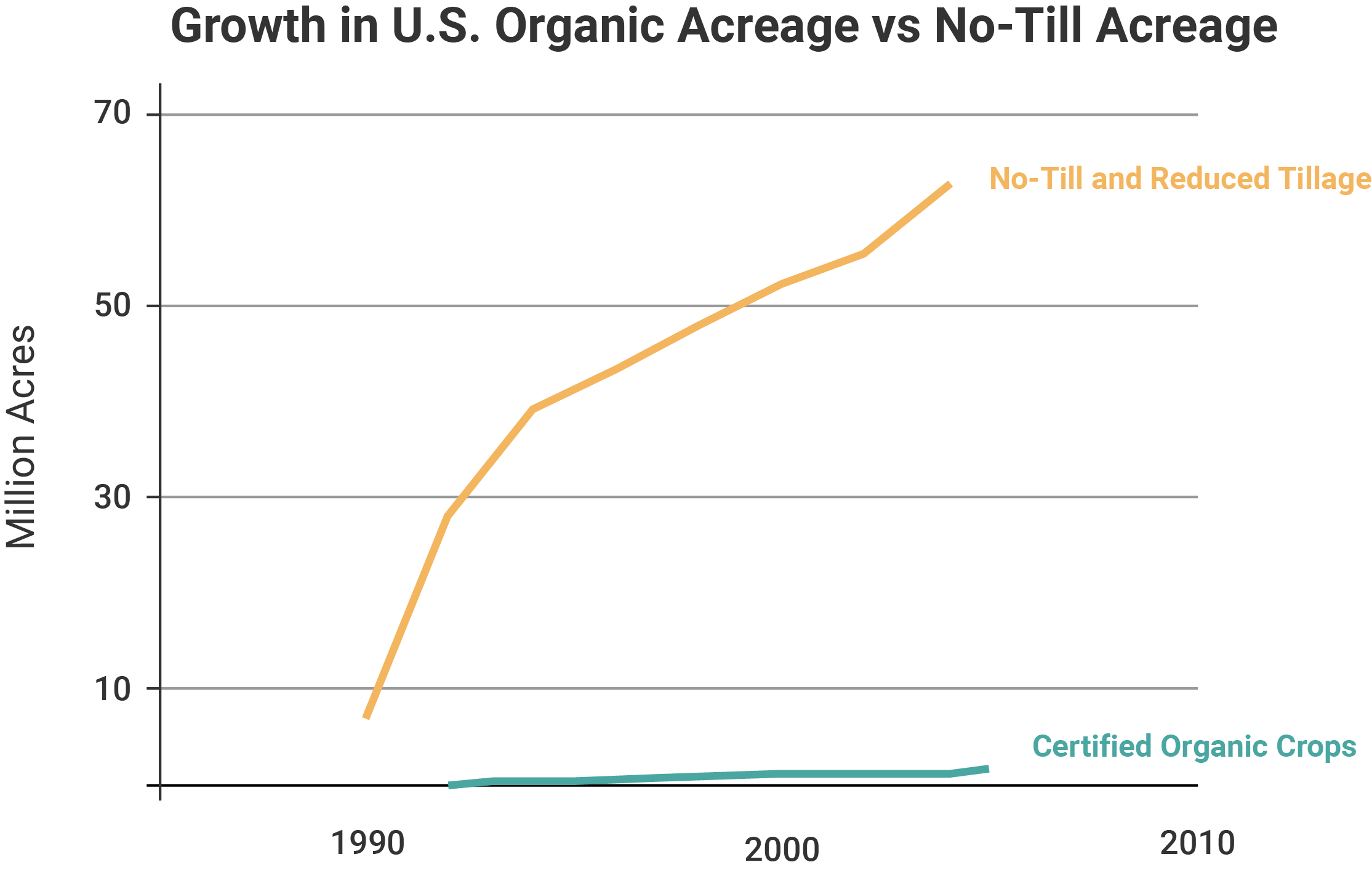

More recently, no-till adoption has continued to rise in many crops (data from the USDA). You can see the rapid rise that followed the release of the first herbicide-tolerant crops and a slower increase as it pushed into areas where no-till is trickier to get up and running:

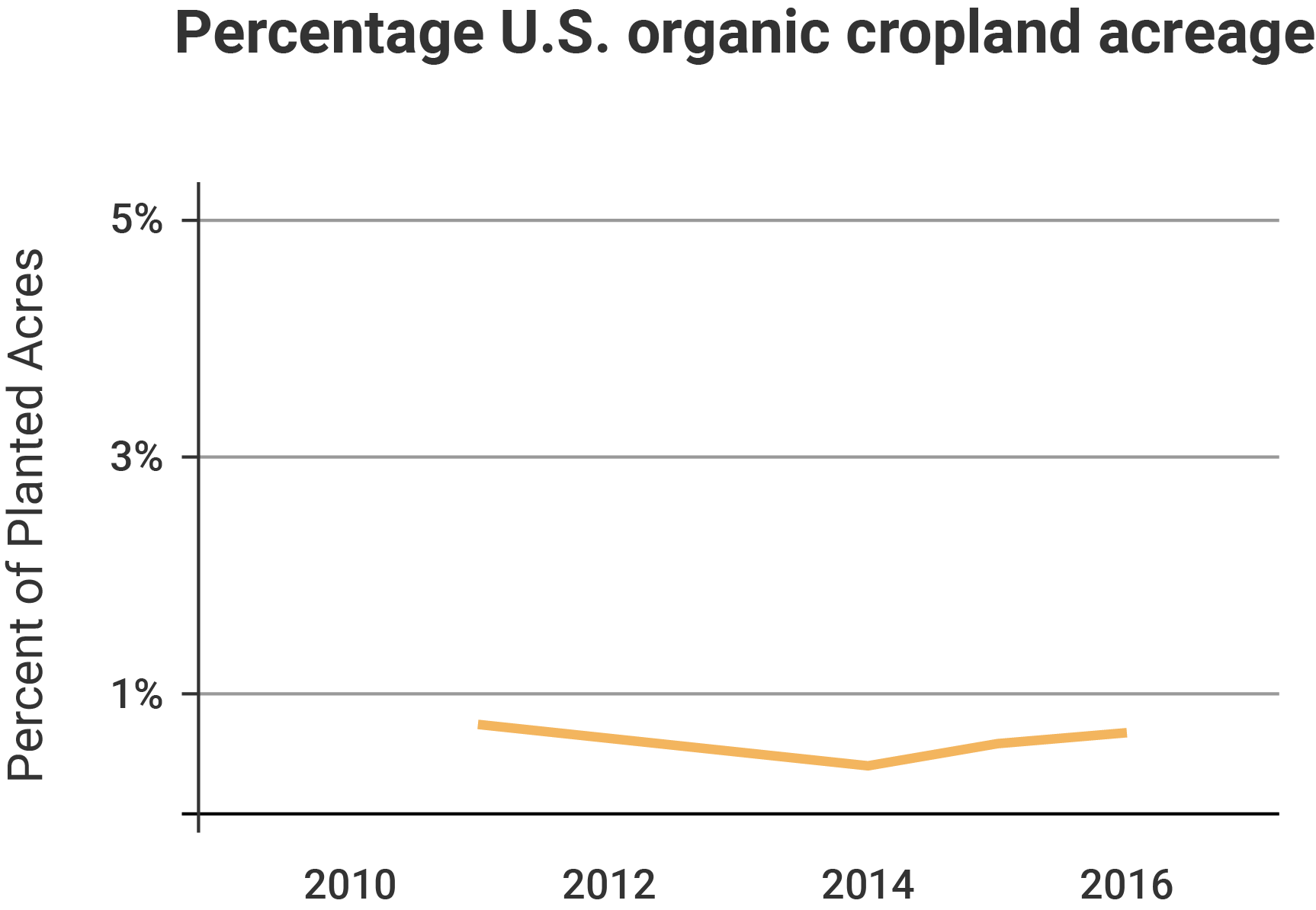

While organic acreage has been slow to increase (organic acreage data and overall cropland acreage data from the USDA):

The decisions surrounding optimal farming practices are complex and often do not fall easily into categories like organic versus conventional. In Part 6, the last article of this series, we explain why many consumers prefer organic produce over conventional produce based on inaccurate assumptions about the role of pesticides in organic and conventional farming.

Marc Brazeau contributed to this report.

Kayleen Schreiber is the GLP’s infographics and data visualization specialist. She researched and authored this series as well as creating the figures, graphs, and illustrations. Follow her at her website, on Twitter @ksphd or on Instagram @ksphd

Marc Brazeau is the GLP’s senior contributing writer focusing on agricultural biotechnology. He also is the editor of Food and Farm Discussion Lab. Marc served as project editor and assistant researcher on this series. Follow him on Twitter @eatcookwrite

This article previously appeared on the GLP February 5, 2019.