A colleague and I wrote about recent Supreme Court decisions that produced sweeping changes in how government regulation works in the United States— shifting power from regulatory agencies to the courts.

The most significant, Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (2024), eviscerated the four-decade-old “Chevron Doctrine” (aka Chevron Deference), which had established that courts should defer to federal agencies to interpret ambiguous statutes as long as Congress has not weighed in on the specific issue in question. The end of deference and the establishment of the right of “judicial veto” will be especially important, we posited, in agencies with esoteric substantive expertise interpreting laws, because it will facilitate legal challenges to established governmental consumer protections, many of which are the responsibility of agencies within the Department of Health and Human Services and other agencies, such as EPA, NOAA, NRC, and OSHA.

We argued that the decisions have “taken the prudence out of jurisprudence,” creating a climate of uncertainty and distrust regarding public policy. More recently, in an article in the Harvard Business Review, scholars Blair Levin and Larry Downes enlarged on the implications of the “judicial veto” of regulatory policies for the U.S. business community.

Their pessimistic view is that far from the business-friendly climate many expected, these SCOTUS decisions threaten to suppress investment, stifle innovation — including the development of new products regulated by federal agencies like FDA and EPA — and entrench the dominance of established corporations.

The new landscape of “Judicial Veto”

Two Supreme Court rulings form the backbone of this transformation, according to Levin and Downes. First, in West Virginia v. EPA (2022), the court significantly restricted the EPA’s ability to regulate carbon emissions, long considered a core part of its authority. This case introduced the major questions doctrine, which stipulates that federal agencies cannot issue rules that have major economic or policy impacts without explicit congressional approval.

In 2023, the court delivered the decisive blow by overturning the Chevron Doctrine which, for almost 40 years, had required courts to defer to agencies’ interpretations of ambiguous statutes, effectively allowing regulators the freedom to interpret and enforce laws in their areas of expertise.

Chevron was important to regulators; the decision had been cited more than 18,000 times over the 40 years it was in place. By repealing Chevron, the court shifted the final say on regulatory matters to the judiciary, granting a “judicial veto” to the nearly 900 federal judges across the U.S. This means that litigants trying to block a regulation can now “judge shop” — find a judge sympathetic to their cause — which is likely to spark a wave of legal challenges to many new rules.

Contrary to the belief that less regulation fosters a better business environment, according to Levin and Downes the SCOTUS decisions are likely to have the opposite effect. Instead of promoting a stable, predictable regulatory framework, the judicial veto will increase uncertainty in three ways:

- Multiplying the number of decision-makers.

- Prolonging the timeline of unpredictability about policy.

- Favoring entrenched businesses over newcomers.

Multiplying decision-makers and discounting expertise

Under the previous regulatory framework, federal agencies primarily arbitrated how laws were interpreted and enforced. They employed subject-matter experts to draft, review, and adjust regulations based on scientific and technological advances and evolving industry needs.

With the shift to judicial oversight, the review of new rules now falls to judges with no expertise in what they are assessing; most lack the specialized knowledge that agencies bring to the table in fast-evolving technologies like artificial intelligence (AI), biotechnology, cryptocurrency, or nuclear power. Without this necessary expertise, judges tasked with ruling on the legality of new rules will inevitably make some fragmented, inconsistent decisions that vary across jurisdictions.

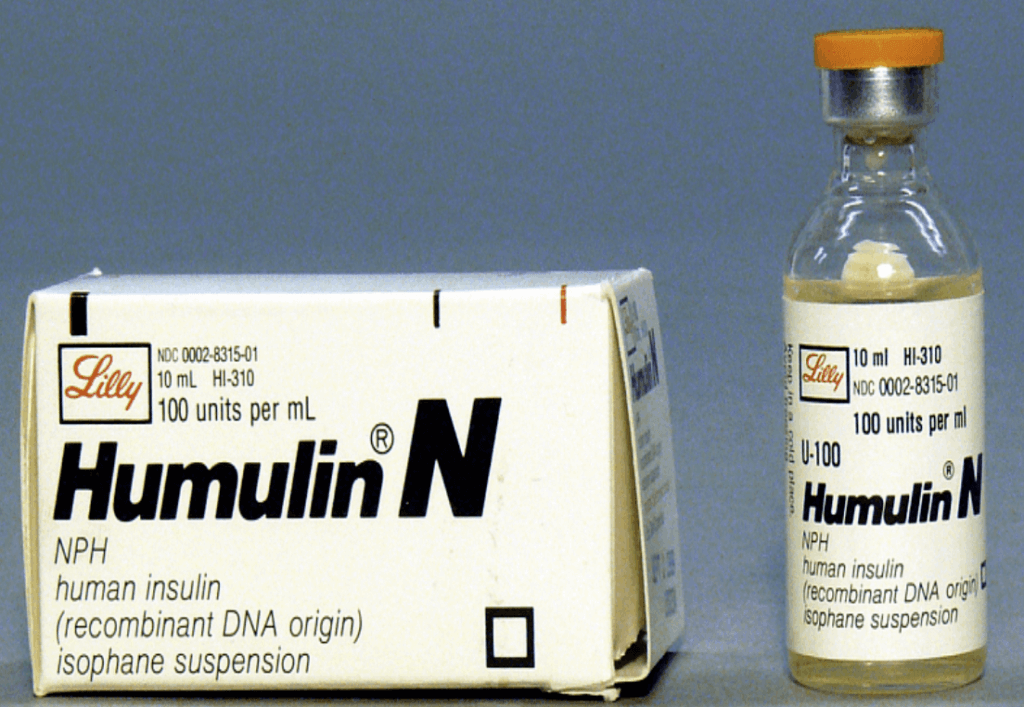

In the 1980s, for example, when the application for approval of the first biopharmaceutical, human insulin produced in genetically engineered bacteria (Humulin), was submitted to the FDA, the agency made a momentous decision that was not spelled out in legislation. They decided because regulators (of whom I was one, heading the review team) already had extensive experience with animal insulins as well as drugs derived from microorganisms, and the genetic engineering techniques employed were viewed by the scientific community as an extension, or refinement, of these methods, no fundamentally new regulatory paradigms were necessary. That proved to be a historic, precedent-setting decision — one that under the current, post-Chevron rules could have been challenged, delaying the approval of life-saving products.

Additionally, as regulations are invalidated at the federal level, states may step in to fill the gap with their own, often conflicting rules, sometimes driven by politics rather than the appropriate expertise. The resulting patchwork of state laws would make it harder for businesses, especially those in emerging industries, to navigate the regulatory landscape.

Prolonging the timeline of unpredictability

In addition to multiplying the number of decision-makers, the judicial veto also increases the amount of time businesses will have to wait for regulatory certainty. Under Chevron, businesses could expect a decision on most regulations within a year or two, with agency expertise guiding the outcome. The courts would often defer to these agencies, meaning businesses that routinely interacted with regulators had a reasonable sense of how new rules would play out and in what timeframe.

Now, that timeline will likely be extended as many new regulations face legal challenges. With cases moving through the courts at the usual glacial pace, businesses could wait five to seven years before knowing the final rules they must comply with. Such prolonged uncertainty is particularly damaging for venture capital and private equity firms, which invest in long-term growth, especially in emerging industries. Investors in AI, nuclear power, pharmaceuticals, and biotechnology, for instance, might hesitate to pour money into companies without knowing whether the regulatory landscape will allow those businesses to succeed. And when judges do make decisions, nothing prevents the new guidelines from being set aside at future proceedings

Tipping the scales in favor of established businesses

The judicial veto also tilts the regulatory playing field in favor of established businesses — which have the legal and financial resources to navigate this new reality — over new entrants and early-stage investors. They can afford to challenge regulations in court and can use litigation as a tool to delay or block new rules that would foster competition.

A less competitive future?

In theory, the judicial veto could stimulate investment in some sectors, particularly those that benefit from reduced regulation. For example, the curtailing of the EPA’s authority under West Virginia v. EPA might encourage investment in fossil fuels like coal — but environmental groups will be ready with endless lawsuits that could be adjudicated in different jurisdictions. It’s not hard to predict chaos is inevitable in many cases.

The uncertain regulatory environment created by the judicial veto will make it harder for entrepreneurs and start-ups to disrupt markets and challenge incumbents. As an experienced management consultant predicted: “Litigation chaos is in our future.” The promise of fewer regulations could be outweighed by the costs of navigating a fractured, unpredictable, and prolonged regulatory landscape.

Levin and Downes’ sardonic conclusion: “[The] judicial veto doctrine may reduce or delay investment across a wide range of industries and businesses. Unless one is investing in law firms.”

Henry I. Miller, a physician and molecular biologist, is the Glenn Swogger Distinguished Fellow at the American Council on Science and Health. He was the founding director of the FDA’s Office of Biotechnology