Nearly two decades after researchers assembled the first genetic blueprint for human life, our understanding of our instruction manual has a dramatic and problematic bias: It’s based primarily on white people.

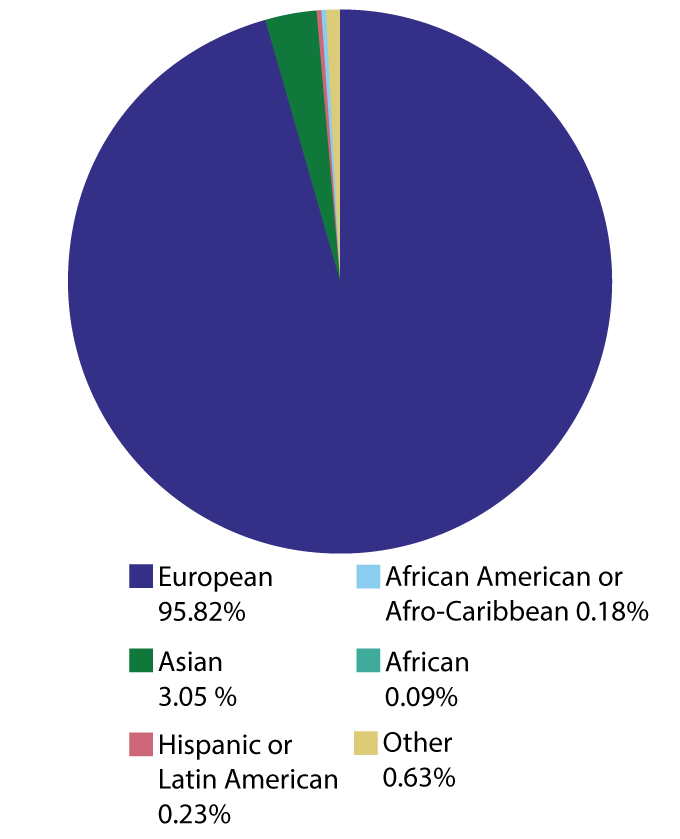

The overwhelming majority of genetic data is from people of European ancestry. As of early January, nearly 96 percent of participants across more than 5,500 studies looking for genetic variants associated with disease or other traits were of European descent, according to the GWAS Diversity Monitor, a real-time online tracker developed and maintained by the Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science at the University of Oxford. Those with African American or Afro-Caribbean ancestry amount to just 0.18 percent of participants; Hispanic or Latino populations just 0.23 percent. That means efforts aspiring to use DNA to identify the best treatments for any individual patient, what’s commonly known as precision medicine, are heavily skewed toward white people.

There are many reasons behind the stark disparity. A big one, says geneticist Tshaka Cunningham, is distrust of the medical community, born from decades of exploitation and abuse: The Tuskegee Study, where white researchers for decades didn’t treat Black men with syphilis, even after penicillin proved effective against the disease. The case of Henrietta Lacks, whose cervical cancer biopsy gave rise to cells that today serve as a crucial resource for scientific studies even though she never gave consent. The forced sterilization of Black, Latina and Indigenous women that was driven by the eugenics movement — the damaging effects of which persist today.

To celebrate our 100th anniversary, we’re highlighting some of the biggest advances in science over the last century. To see more from the series, visit Century of Science.

READ MORE

What happened to Lacks, for example, “left a scar on many a minority person,” Cunningham says. “It’s like, ‘Am I gonna get Henrietta Lacks-ed or Tuskegee-ed?’”

Cunningham is working with others to build trust and overcome the damage of the past. He is chief scientific officer of Polaris Genomics, a company studying the genetic underpinnings that put some people at increased risk of certain behavioral health conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder. He is also executive director of the Faith Based Genetic Research Institute, a nonprofit that aims to educate people, primarily people of color, about the value of engaging with the medical community and genetics research.

Science News’ Erin Garcia de Jesús spoke with Cunningham about the need for diverse data in genetics and the challenges researchers face in reaching minority groups.

Garcia de Jesús: Why is it important to have diverse participants in genetics research?

Cunningham: One is the societal imperative for equity — and having research, and products [such as genetic tests and treatments] be broadly available for people. You don’t want to have health disparities between communities. And when it comes to genetics, genomics and precision medicine, you already see this growing divide pushed by one-sided research. Mostly Caucasian groups have been included in genomic research to date, yet the results are meant to be applied to all others too.

There are genetic tests, for example, that have been developed based on research in specific communities. Like for BRCA1. [Mutations in the gene have been linked to a higher risk of breast cancer and are commonly considered in deciding on treatment approach.] You may have a set of BRCA1 mutations that have been defined from studies in Caucasian female populations, but those variants might not be the same variants present in minority female populations, particularly people of African descent or African Americans. So how good is the BRCA1 test for a community of African American patients? Probably not so good.

Then there’s the scientific imperative. Even if you don’t feel strongly about equality for equality’s sake, you can appreciate that for scientific reasons, we want to have as diverse a dataset as we can. That’s how we can really understand the universe of potential genetic variation and what it means.

Geneticist Tshaka Cunningham aims to educate people, primarily people of color, about the value of engaging with the medical community and genetics research.Polaris Genomics

Geneticist Tshaka Cunningham aims to educate people, primarily people of color, about the value of engaging with the medical community and genetics research.Polaris Genomics

Garcia de Jesús: What prevents that kind of diversity in current studies?

Cunningham: I think in the United States — and I can really speak only from my experience in the United States — it’s because of the history of racial and ethnic division in our country, and some of the crimes that have been perpetrated on specific groups, even in medical science. African Americans have lived through slavery. They’ve lived through Jim Crow. They’ve lived through Tuskegee. They’ve lived through Henrietta Lacks. And they’ve lived through, in their own lives, any number of discriminations at the hands of the medical system. It creates systemic distrust for many from the African American community that would make them hesitant to participate in scientific studies.

The Latino population may have different reasons. If you’re in the United States and you’re a recent immigrant who is not necessarily documented, you might not trust the establishment with your information. Or even if you are documented, you may not trust the establishment.

The Tuskegee study left a lot of psychological damage in certain communities. It’s created a severe mistrust that can often work counter to people’s overall health — the hesitancy to participate in genetic studies that could greatly benefit the community by driving developments in precision medicine, and even the hesitancy to take the vaccine for COVID-19. That distrust took hundreds of years to develop. We’re only in the last few decades really trying to do anything meaningful to address it.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Garcia de Jesús: What kind of work are you doing to overcome that distrust?

Cunningham: Our goal at the Faith Based Genetic Research Institute is to build some of those trust bonds, particularly through communities of faith — African American churches, Latino churches and others who are meeting people where they are in a religious context. Our goal is also to share information about how precision medicine, gene therapy, gene editing and advanced technology are going to impact the medical field and impact people’s health and well-being, but through trusted sources who are folks from their community.

One of the strategies we employ is called the honest broker strategy; the people who are talking about the technology to the community are from the community. [We think about] who’s representing the science, who’s communicating the science, who’s telling you why you should participate. So I’m not bringing a bunch of white, male scientists into a community of African American and Latino churchgoers. I’m bringing in Black male and Black female scientists who are from the community.

It’s challenging because you don’t have as many scientists of color. There’s a training issue on that part. I think the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation and other organizations have done a good job of identifying the problem. I’m hoping that they will come up with some real tactical solutions.

Mostly white

As of January, participants in genome-wide association studies, used to uncover common genetic variants that might explain why one person is more susceptible to an illness than another, for example, were overwhelmingly European, or white, leaving other groups underrepresented.

Ancestry of participants in genome-wide association studies as of January 2022 E. OtwellE. Otwell Source: GWAS Diversity Monitor

E. OtwellE. Otwell Source: GWAS Diversity Monitor

Garcia de Jesús: What kind of information do you share in these community meetings, and have you seen success?

Cunningham: We have a preview lecture called DNA 101. We walk through, what is DNA? What is a mutation? What is a single nucleotide polymorphism, and how do they apply to health and disease? Why is it important for you to know what single nucleotide polymorphisms are? Because it’ll help you get a better idea of what diseases you’re predisposed to. And to give you a leg up on treatment.

That’s where we meet people. And we’ve had a lot of success. Generally after one of our in-person sessions — which we haven’t been able to do since COVID-19 — we’ve had a lot of interest from folks, some who came with questions and some who had never been approached about getting a genetic test before.

We have one grant called the PeopleSeq Consortium in partnership with places including the Broad Institute and Harvard University that surveys individuals’ attitudes toward participating in elective genetic testing. Before we joined the effort, the program had five African Americans who completed the survey and sent their samples for testing. After we got involved, that number increased to 50 within one year. Our work is making a difference, but we still have a long way to go.

Garcia de Jesús: Looking back at how far genetics research has come, where do you think it’s headed?

Cunningham: There’s a research imperative to understand every genome, because all genomes matter. But we have to make sure that we go above and beyond what we’ve been doing to understand minority genomes, because minority genomes especially matter. They have not been studied. I think it is long overdue.

Science has long been the domain of the wealthy, who have been in positions to define the pace and the communities that get studied. We’ve got to get out of that. As a community, we’ve got to say, “No, that’s not in the best interest of science, and it’s not in the best interest of society.” So let’s really lean in and do it different.

I’m hopeful that newer generations of researchers — Caucasian and nonminority researchers — are realizing that and saying “Hey, look, we can’t do business as we did. We’re really going to try to open this up and diversify for the sake of science and the sake of society.”