No plant should have to end this way.

North America’s various beach plums bear purple-blue, cherry-sized fruits that make for a beloved New England jelly. The small trees’ tolerance for salty, wind-blasted shores impresses biologists. But even a beach plum has limits.

One of the plum’s distinctive forms, named in 1897 for physician Charles B. Graves who called attention to the plant, may have gone extinct in the wild in large part because people like a little privacy when they need a bathroom break on the beach.

All of the known Graves’ beach plums grew in a cluster on a ridge overlooking the Connecticut shore in Groton. It “was the only shade on the beach,” says botanist Wesley Knapp, who studies extinctions with the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program in Raleigh. Beachgoers seeking discreet foliage gravitated to Prunus maritima var. gravesii, relentlessly delivering excess nitrogen. “I can’t think of a worse way … to go extinct,” Knapp says.

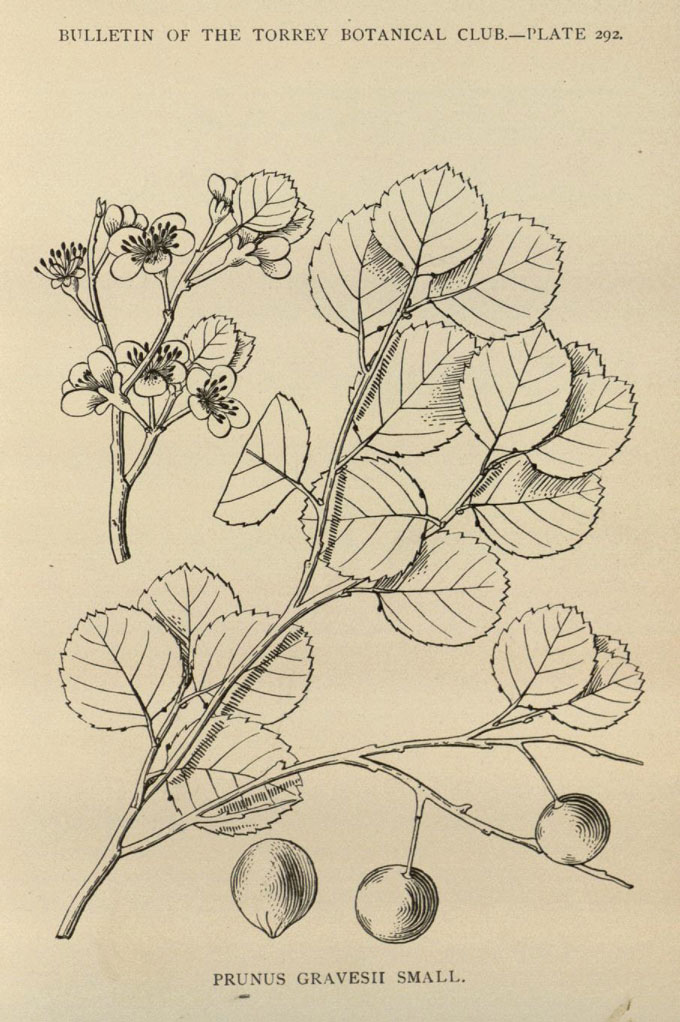

Graves’ beach plum experienced one of the more undignified extinctions in the wild. An 1897 drawing shows the shrub’s small fruit and distinctive round leaves.Peter H. Raven Library/Missouri Botanical Garden

Graves’ beach plum experienced one of the more undignified extinctions in the wild. An 1897 drawing shows the shrub’s small fruit and distinctive round leaves.Peter H. Raven Library/Missouri Botanical Garden

He has now determined that Graves’ beach plum and four other kinds of U.S. plants that have been wiped out in the wild still grow in at least one garden somewhere. Ongoing quests might reveal two more. Dozens of others, however, are gone.

Focusing on U.S. and Canadian green heritage, Knapp and colleagues declared August 28 in Conservation Biology that 58 plants are extinct in the wild, with no miracle rescues in gardens. That totals 65 known losses from the wild, about 1.4 per decade, since Europeans started settling in the mid-1500s.

“We are positive it is a gross underestimate,” Knapp cautions. The team’s methods were conservative: going plant name by name and declaring a loss of a full species or a distinctive lineage within a species only if detailed information existed.

Knapp, however, doesn’t come across as a gloomy guy. He calls his motivational spiel about conserving native plants “Tales from the Crypt,” and he chats colorfully about plants and the people who love them. Many of his colleagues do too. The possibility of snatching a flower or fern from the jaws of extinction has fired up a community of enthusiasts trying to document and protect what’s left of the rarest of native vegetation. The challenge is immense, but sometimes there are wins. It’s good practice in the art of hope.

Wild losses

To Anne Frances, a coauthor with Knapp on the extinction tally, “the one that stands out” is the Franciscan manzanita (Arctostaphylos franciscana), a sprawling woody plant with seeds that become more likely to sprout when cued by a fire’s smoke.

Frances watches over native flora as the lead botanist at NatureServe, a nonprofit based in Arlington, Va., that keeps a giant database on the status of plants in the United States and Canada. She’s the person who switches a plant’s status to “extinct” in the database, and those keystrokes still get to her.

She was recently pandemic-teleworking and listening to a meeting when she remembered she needed to update the status on a plant that hadn’t been seen for decades. The meeting suddenly stopped. Someone inquired if she was OK. She hadn’t realized that as she finally clicked the entry to “extinct,” she had let out a deep sigh.

The manzanita extinction story, though, has had a happy twist.

Tough, resilient Franciscan manzanita, which belongs to the same family as blueberries and rhododendrons, spreads red-barked, low-growing greenery and dangles pale little urn-shaped flowers. It’s one of several manzanitas that once grew on San Francisco’s serpentine barrens, dry outcroppings laden with heavy metals from greenish, vaguely snakeskin-textured rocks.

The shrub got its species name in 1905 from Toronto-born botanist Alice Eastwood, a rarity herself in the staggeringly male sciences. At age 6, she lost her mother. Despite her hard-luck childhood trying to look out for two younger siblings and cope with her father’s faltering business ventures, she finished high school in Denver. That was the end of her formal education, but she showed great aptitude for botany. During summers she went collecting, preferring to travel solo, even in rugged terrain. She switched from riding side-saddle in voluminous skirts to riding astride in (gasp) denim garments of her own practical design.

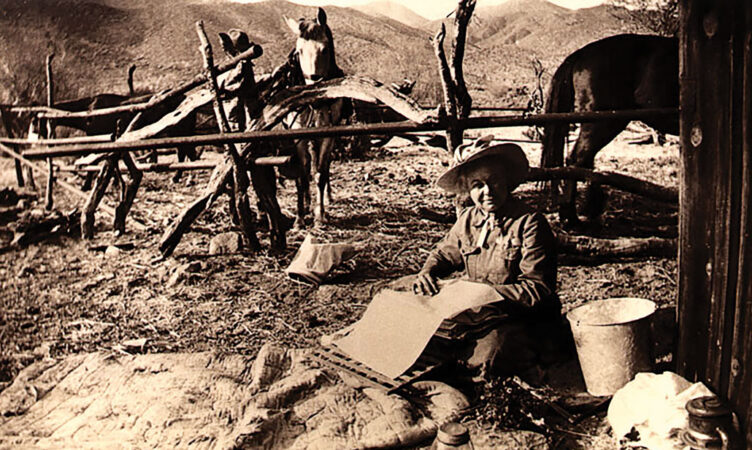

Self-taught botanist Alice Eastwood named the Franciscan manzanita species. Shown in 1913 in San Diego County with a plant press in her lap, she didn’t let long skirts keep her from field expeditions. California Academy of Sciences

Self-taught botanist Alice Eastwood named the Franciscan manzanita species. Shown in 1913 in San Diego County with a plant press in her lap, she didn’t let long skirts keep her from field expeditions. California Academy of Sciences

Being a woman didn’t prevent Eastwood from getting a botanist’s job at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. She was recruited by Katharine Brandegee, a town constable’s widow who consoled herself by earning an M.D. from the University of California in 1878 and then took charge of the academy’s herbarium, a kind of library of preserved plant samples.

Eastwood took over from her, and before retiring at the age of 90, named dozens of species, including the Franciscan manzanita.

On the morning of the 1906 earthquake, as fire neared the academy, Eastwood and a few colleagues struggled into the damaged building for last-minute salvaging. The marble staircase was “in ruins and we went up chiefly by holding on to the iron railing and putting our feet between the rungs,” she wrote in a letter published in the May 25, 1906 Science. She and a helper lowered down with cords more than 1,000 of the most valuable pressed plants from an upper floor, including the definitive specimen of Franciscan manzanita.

Yet, as the city recovered and grew, serpentine barrens and their specialized plants disappeared under roads and buildings. Nurseries sold garden versions of it, but the last wild Franciscan manzanita sighting was recorded in 1947.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Of all places

It wasn’t truly the last, we now know. At some unknown point, another manzanita sprouted, unrecognized and in a most awkward spot. Overgrown by weedy Australian tea trees, English ivy and such, the last known wild Franciscan manzanita grew on a traffic island shaped like a teardrop.

On its east side sped six lanes of traffic to and from the Golden Gate Bridge and on the west lay a six-meter drop to a highway on-ramp. This section of Doyle Drive was deemed seismically unsafe, and California OK’d its demolition. Native plant activists didn’t protest to save the manzanita. They had no idea it was there.

By 2009, 100,000 vehicles whooshed by every day, oblivious. Even the impassioned protector of native plants and a coauthor on Knapp’s extinctions paper, Dan Gluesenkamp, “quite frequently” drove by, he says, on the way from his San Francisco home to 31 plant restoration sites he worked on to the north. “We all missed it,” he says.

As highway work progressed, a crew with a great roaring wood chipper arrived on the traffic island to grind up weeds. On this particular day, Gluesenkamp learned, a California highway patrol car had parked at the curb near the manzanita. The landscape crew positioned its machinery to spew chips away from, rather than toward, the law. While the rest of the island’s plants ended the day either as mulch or under it, the newly exposed manzanita lived to see another rush hour.

On October 16, Gluesenkamp was driving home from a conference where he had argued that the best strategy for conserving botanical heritage in a changing climate was to find all of California’s rare native plants and protect them individually.

“It’s really crazy that after making that pitch … I spotted an extinct plant,” he says. Drive-by resurrecting an impossible plant is rare even for him. “I was roaring by at (a little over) freeway speeds, but something just clicked,” he says.

Or almost clicked. He recognized an unusual manzanita, but suspected it was a different rarity: A. montana ssp. ravenii, which still hangs on, barely, elsewhere in the wild. But a new patch of any rare plant is good news. With such pathetically tiny shreds left of any rare plant’s original genetic diversity, even a single new wildling could improve a species’s chances of coping with our fast-changing world.

Gluesenkamp drove by the traffic island twice more. He made a phone call, and two botanists rushed over, dodging on foot lane after lane of traffic to see the plant up close. Not until a fourth expert weighed in, though, did realization dawn that this could be a species that had supposedly vanished from the wild more than 60 years earlier.

Electrifying as the rediscovery was, it didn’t stop highway construction. Conservationists eventually opted to try transplanting the priceless last wild manzanita to San Francisco’s Presidio park.

Moving day began on a Saturday in January 2010 at around 3 a.m. in rain with occasional hail. The storm so worried one of the operation’s contractors that an employee spent the night on the traffic island to make sure a canopy covering the plant did not blow away. A 75-ton crane nudged into place to pick up the plant with its own minor continent of surrounding soil.

To prepare for transporting this one plant to the park, San Francisco took the extraordinary step of shutting down the MacArthur Tunnel, one of its busiest arteries. While the city slept, Gluesenkamp says, “we had a crazy, slow-moving parade.”

He and colleagues described the rediscovery and replanting in a 2009/2010 issue of Fremontia in what must be one of the most suspenseful accounts ever published of transplanting shrubbery. Ten years later, Gluesenkamp, now director of the California Native Plant Society, still remembers those hours as “incredibly nerve-racking.”

The mother plant has survived so far, he reports. Carefully tended cuttings and shoots are doing well. All this coddling from specialists means the plant no longer really counts as a manzanita living on its own. So it has now gone extinct in the wild — for the second time.

Search parties

The tale of another plant on NatureServe’s extinction list follows a different arc. A tiny parasitic flower in a group called fairy lanterns was vanishingly rare to begin with. It’s the only one of more than 70 known species to have turned up — briefly — in North America. More people have walked on the moon than are on record as viewing Thismia americana growing on Earth. Yet for decades, crowds have shown up to keep searching.

Norma Etta Pfeiffer started her career in 1913 as the University of Chicago’s youngest Ph.D. and later studied lilies (shown) at the Boyce Thompson Institute in New York. She is famous for her student work on a lost Thismia species.Boyce Thompson Institute

Norma Etta Pfeiffer started her career in 1913 as the University of Chicago’s youngest Ph.D. and later studied lilies (shown) at the Boyce Thompson Institute in New York. She is famous for her student work on a lost Thismia species.Boyce Thompson Institute

The only places on the planet this Thismia has been reported were two marshy scraps of prairie in southeastern Chicago. The city had long drawn botanists of international standing. Classes at the University of Chicago even used one of the plant’s wetland homes for field trips. Yet that’s not how the discovery played out, according to letters written by the plant’s first chronicler, Norma Etta Pfeiffer.

In August 1912, Pfeiffer was a graduate student at the University of Chicago with bad luck in the job market. A college where she had accepted a job teaching botany had withdrawn the offer before she could arrive, according to family lore. The school had found a man willing to take the job after all.

Thus she was heading to the University of North Dakota as a botany instructor. The professor who hired her had been so evasive about exactly what her salary would be that she had agreed to work a second job as governess for his two daughters.

Pfeiffer was also unsure whether she would find plant materials there for her classes. So, before leaving Chicago, she and another female grad student went collecting in a swath of damp prairie called Solvay amid a riot of black-eyed Susan, multiple kinds of goldenrod, wild irises and other plants. It’s now concrete-covered cityscape near 119th Street and some railroad tracks.

Down on hands and knees looking for liver-worts, “suddenly I saw my first specimen of Thismia, a tiny flower half-imbedded in the soil,” she wrote.

About half as wide as a pinkie fingertip, Thismia’s cup-shaped white flowers, with blue-green tints, sprout three petals that touch at the top, while flaps in between loll down like tongues. The rest of the plant lies underground as ghostly pale strings.

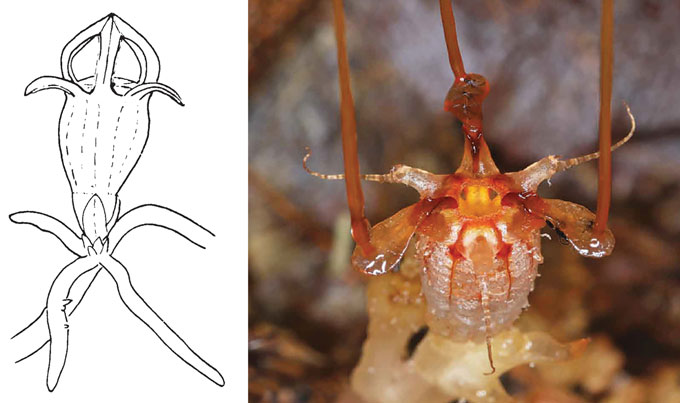

Tiny flowers of Borneo’s parasitic Thismia neptunis (photographed in 2017, right) hadn’t been seen for 151 years. Recent sightings raise hopes for finding T. americana (illustrated, left), missing for a mere 104.From Left: N.E. Pfeiffer/Botanical Gazette 1914; M. Sochor et al/Phytotaxa 2018

Tiny flowers of Borneo’s parasitic Thismia neptunis (photographed in 2017, right) hadn’t been seen for 151 years. Recent sightings raise hopes for finding T. americana (illustrated, left), missing for a mere 104.From Left: N.E. Pfeiffer/Botanical Gazette 1914; M. Sochor et al/Phytotaxa 2018

After baffling three of her professors, Pfeiffer tried a fourth. “With all his knowledge of world flora, he had never seen it,” she wrote. She had a new thesis topic.

She took specimens with her to her new job. “In North Dakota, I used all the time I was free from earning my living to make preparations and study them,” she wrote. In time she realized her odd plant belonged among the extreme parasites in the genus Thismia, described in 1844 and named as an anagram for English anatomist Thomas Smith. Smithia was already taken.

Her Thismia work earned her a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in 1913. During a visit the next year, her first prairie site had a barn and no Thismia. A letter she wrote years later revealed a second prairie patch, where in 1916, she was the last person to document the plant’s presence.

After a decade of teaching in North Dakota with various frustrations, she left and had a long career at the Boyce Thompson Institute in Yonkers, N.Y. (now in Ithaca). Her Thismia discovery got a one-sentence mention in her New York Times obituary in 1989. The headline read “Norma Pfeiffer, expert on lilies, dies at 100.”

Thismia hunts on remaining scraps of prairie in and around Chicago, like one promoted in this poster in 2011, have become public events. The gatherings have enriched knowledge of other local flora.Joe Taylor

Thismia hunts on remaining scraps of prairie in and around Chicago, like one promoted in this poster in 2011, have become public events. The gatherings have enriched knowledge of other local flora.Joe Taylor

By 1951, others were on the lookout for Thismia in Chicago. One search featured two lichen specialists, presumably experts in spotting tiny things. Later efforts attracted hot-shot botanists from out of state as well as local talent. The efforts succeeded in adding dozens of previously unnoticed plants to lists of riches in remaining prairies, but not in finding Thismia.

More recent searches have shifted to merry public events. “August is when Norma found the plant, so that is when we look for it,” says Linda Masters, a leader of multiple hunts and a restoration specialist at the regional conservation group Openlands in Chicago. “August in Chicago is notoriously hot, humid and buggy.” Yet usually a little more than 100 people show up. A couple of times, some promising little mystery nubbin that suggested Thismia turned up. “Hearts stopped, and people studied the discovery,” Masters says. “But nope.”

In 2017, a different long-lost Thismia, T. neptunis, resurfaced in Borneo. This species may not be astonishingly rare. It’s just really hard to spot. “Even if you know roughly what you are looking for, it takes weeks to find the first one,” says one of its rediscoverers, Michal Sochor of the Crop Research Institute in Olomouc, Czech Republic.

Variety show

The American Thismia ranks as a full species, but variations of species are important too; 14 kinds of plants on Knapp and company’s new list are distinct lineages within a species. Consider, for example, Cheatum’s Eastern wahoo.

In fall, the leaves and seedpods of Eastern wahoos (Euonymus atropurpureus), a kind of shrub native to the central and eastern United States, burst into various candy reds and purples. Botanists can find the species in the wild, and people plant them in their yards.

Conserving plants, however, is not like stamp collecting. Knapp and colleagues aren’t looking just for an exemplar or two of a plant. Instead, conservationists now seek genetic variation that gives the plants more options for what the future will throw at them. One taxonomist’s variety may be another’s “nothing special,” so the coauthors of the paper agreed to a voting system that would identify plant variations that the majority agreed were distinctive. Cheatum’s Eastern wahoo made the cut.

This wahoo grew in a small area around Dallas. Last reported in 1944, the shrub appears in the assessment as extinct in the wild (possibly done in by insects) but with a question mark about gardens. The last known place on Earth that a Cheatum’s Eastern wahoo from Texas might grow is the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. Knapp has his fingers crossed and is waiting to hear.

He’s also waiting to hear from the National Botanic Garden of Latvia, the last known hope for, of all things, the Delaware hawthorn, named after its American home state. That small white-flowered tree was named Crataegus delawarensis in 1903 by Charles Sprague Sargent, the first director of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University and an enthusiastic sharer of plants.

Knapp did hear back from a query that the Morton Arboretum in Lisle, Ill., had what could be another of Sargent’s hawthorns, C. fecunda. “I was really dubious, because these things can be easily misidentified,” Knapp says. Everyone had to wait until the next spring, because an important distinguishing trait shows up in flowers.

When the tree put out its clusters of white petals, Matt Lobdell, Morton’s curator of living collections, photographed the white flowers against a white sheet of paper. Scrutinizing the images, the author of a book on southeastern hawthorns decided that Morton’s single tree was the last of its species. “It was a real wow moment,” Knapp says.

He had three more occasions, while working on the extinction list, to startle caretakers with the news that they were managing catastrophically rare plants. Letting a species or variety dwindle to just a few individuals is a conservation nightmare.

The lone C. fecunda, growing at the Illinois arboretum since 1922, no longer shows much vigor, Lobdell says. That doesn’t bode well for next spring’s efforts to propagate the plant. “If we’d got on top of this … 70 years ago, we may have had more options,” he says.

Lobdell is trying to do just that for future conservation of three oak species, native to the southern United States. He’s gone plant collecting from South Carolina to Alabama to start banking oak genetic diversity in the arboretum. “Instead of having just three Georgia oaks, all from the same population, we can maybe have 50 or 200,” he says.

Exciting as it is to un-extinct species from a car window or keep hope alive for a miracle in next year’s prairie mud, what plants really need from humans is less drama and more smart planning.

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.

Subscribe or Donate Now