Under a midday summer sun in California’s Sacramento Valley, rice farmer Peter Rystrom walks across a dusty, barren plot of land, parched soil crunching beneath each step.

In a typical year, he’d be sloshing through inches of water amid lush, green rice plants. But today the soil lies naked and baking in the 35˚ Celsius (95˚ Fahrenheit) heat during a devastating drought that has hit most of the western United States. The drought started in early 2020, and conditions have become progressively drier.

Low water levels in reservoirs and rivers have forced farmers like Rystrom, whose family has been growing rice on this land for four generations, to slash their water use.

Rystrom stops and looks around. “We’ve had to cut back between 25 and 50 percent.” He’s relatively lucky. In some parts of the Sacramento Valley, depending on water rights, he says, farmers received no water this season.

California is the second-largest U.S. producer of rice, after Arkansas, and over 95 percent of California’s rice is grown within about 160 kilometers of Sacramento. To the city’s east rise the peaks of the Sierra Nevada, which means “snowy mountains” in Spanish. Rice growers in the valley below count on the range to live up to its name each winter. In spring, melting snowpack flows into rivers and reservoirs, and then through an intricate network of canals and drainages to rice fields that farmers irrigate in a shallow inundation from April or May to September or October.

If too little snow falls in those mountains, farmers like Rystrom are forced to leave fields unplanted. On April 1 this year, the date when California’s snowpack is usually at its deepest, it held about 40 percent less water than average, according to the California Department of Water Resources. On August 4, Lake Oroville, which supplies Rystrom and other local rice farmers with irrigation water, was at its lowest level on record.

Drought in the Sacramento Valley has forced Peter Rystrom and other rice farmers to leave swaths of land barren.N. Ogasa

Drought in the Sacramento Valley has forced Peter Rystrom and other rice farmers to leave swaths of land barren.N. Ogasa

Not too long ago, the opposite — too much rain — stopped Rystrom and others from planting. “In 2017 and 2019, we were leaving ground out because of flood. We couldn’t plant,” he says. Tractors couldn’t move through the muddy, clay-rich soil to prepare the fields for seeding.

Climate change is expected to worsen the state’s extreme swings in precipitation, researchers reported in 2018 in Nature Climate Change. This “climate whiplash” looms over Rystrom and the other 2,500 or so rice producers in the Golden State. “They’re talking about less and less snowpack, and more concentrated bursts of rain,” Rystrom says. “It’s really concerning.”

Farmers in China, India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Vietnam — the biggest rice-growing countries — as well as in Nigeria, Africa’s largest rice producer — also worry about the damage climate change will do to rice production. More than 3.5 billion people get 20 percent or more of their calories from the fluffy grains. And demand is increasing in Asia, Latin America and especially in Africa.

To save and even boost production, rice growers, engineers and researchers have turned to water-saving irrigation routines and rice gene banks that store hundreds of thousands of varieties ready to be distributed or bred into new, climate-resilient forms. With climate change accelerating, and researchers raising the alarm about related threats, such as arsenic contamination and bacterial diseases, the demand for innovation grows.

“If we lose our rice crop, we’re not going to be eating,” says plant geneticist Pamela Ronald of the University of California, Davis. Climate change is already threatening rice-growing regions around the world, says Ronald, who identifies genes in rice that help the plant withstand disease and floods. “This is not a future problem. This is happening now.”

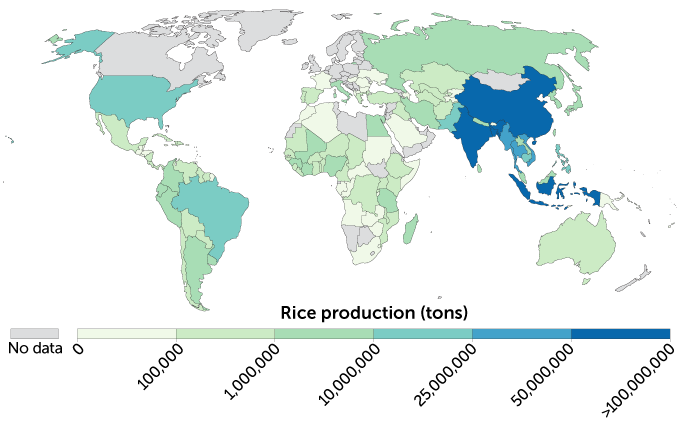

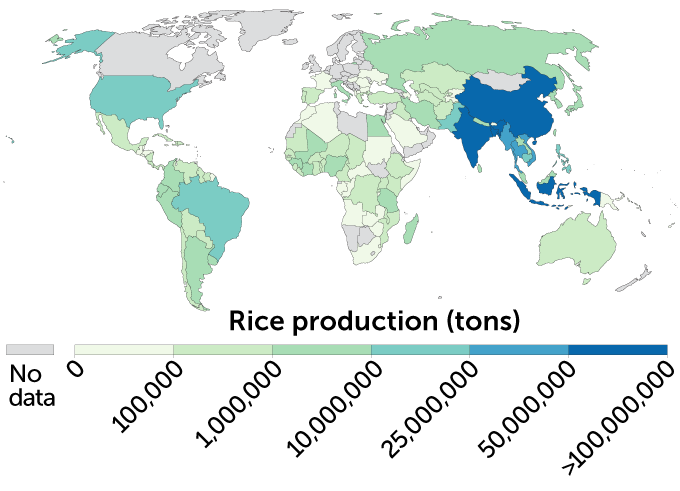

The top rice producers are in Asia

The world’s top rice producer is China, at 214 million metric tons. India, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Vietnam are next. In Africa, Nigeria (6.8 million) is the largest producer. Brazil (11.8 million) and the United States (10.2 million) are also top producers, according to 2018 data from the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization.

Worldwide rice production, 2018  OurWorldinData.org

OurWorldinData.org  OurWorldinData.org Source: FAO

OurWorldinData.org Source: FAO

Saltwater woes

Most rice plants are grown in fields, or paddies, that are typically filled with around 10 centimeters of water. This constant, shallow inundation helps stave off weeds and pests. But if water levels suddenly get too high, such as during a flash flood, the rice plants can die.

Striking the right balance between too much and too little water can be a struggle for many rice farmers, especially in Asia, where over 90 percent of the world’s rice is produced. Large river deltas in South and Southeast Asia, such as the Mekong River Delta in Vietnam, offer flat, fertile land that is ideal for farming rice. But these low-lying areas are sensitive to swings in the water cycle. And because deltas sit on the coast, drought brings another threat: salt.

Salt’s impact is glaringly apparent in the Mekong River Delta. When the river runs low, saltwater from the South China Sea encroaches upstream into the delta, where it can creep into the soils and irrigation canals of the delta’s rice fields.

In Vietnam’s Mekong River Delta, farmers pull dead rice plants from a paddy that was contaminated by saltwater intrusion from the South China Sea, which can happen during a drought.HOANG DINH NAM/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

In Vietnam’s Mekong River Delta, farmers pull dead rice plants from a paddy that was contaminated by saltwater intrusion from the South China Sea, which can happen during a drought.HOANG DINH NAM/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

“If you irrigate rice with water that’s too salty, especially at certain [growing] stages, you are at risk of losing 100 percent of the crop,” says Bjoern Sander, a climate change specialist at the International Rice Research Institute, or IRRI, who is based in Vietnam.

In a 2015 and 2016 drought, saltwater reached up to 90 kilometers inland, destroying 405,000 hectares of rice paddies. In 2019 and 2020, drought and saltwater intrusion returned, damaging 58,000 hectares of rice. With regional temperatures on the rise, these conditions in Southeast Asia are expected to intensify and become more widespread, according to a 2020 report by the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific.

Then comes the whiplash: Each year from around April to October, the summer monsoon turns on the faucet over swaths of South and Southeast Asia. About 80 percent of South Asia’s rainfall is dumped during this season and can cause destructive flash floods.

Bangladesh is one of the most flood-prone rice producers in the region, as it sits at the mouths of the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers. In June 2020, monsoon rains flooded about 37 percent of the country, damaging about 83,000 hectares of rice fields, according to Bangladesh’s Ministry of Agriculture. And the future holds little relief; South Asia’s monsoon rainfall is expected to intensify with climate change, researchers reported June 4 in Science Advances.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

A hot mess

Water highs and lows aren’t the entire story. Rice generally grows best in places with hot days and cooler nights. But in many rice-growing regions, temperatures are getting too hot. Rice plants become most vulnerable to heat stress during the middle phase of their growth, before they begin building up the meat in their grains. Extreme heat, above 35˚ C, can diminish grain counts in just weeks, or even days. In April in Bangladesh, two consecutive days of 36˚ C destroyed thousands of hectares of rice.

In South and Southeast Asia, such extreme heat events are expected to become common with climate change, researchers reported in July in Earth’s Future. And there are other, less obvious, consequences for rice in a warming world.

One of the greatest threats is bacterial blight, a fatal plant disease caused by the bacterium Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. The disease, most prevalent in Southeast Asia and rising in Africa, has been reported to have cut rice yields by up to 70 percent in a single season.

“We know that with higher temperature, the disease becomes worse,” says Jan Leach, a plant pathologist at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. Most of the genes that help rice combat bacterial blight seem to become less effective when temperatures rise, she explains.

And as the world warms, new frontiers may open for rice pathogens. An August study in Nature Climate Change suggests that as global temperatures rise, rice plants (and many other crops) at northern latitudes, such as those in China and the United States, will be at higher risk of pathogen infection.

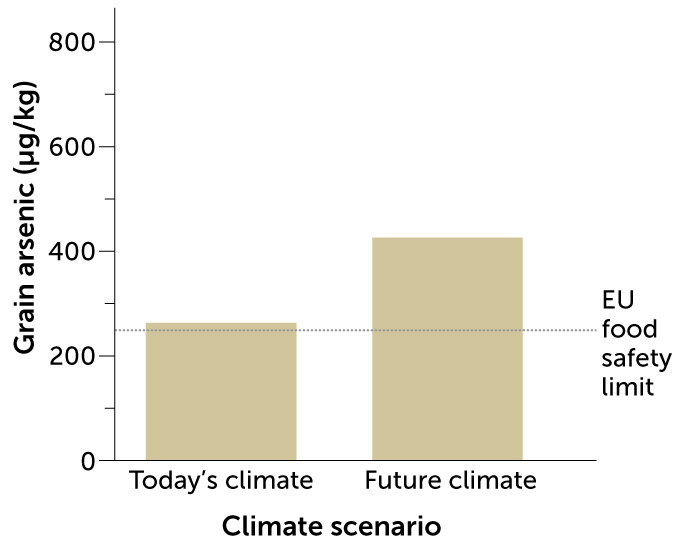

Meanwhile, rising temperatures may bring a double-edged arsenic problem. In a 2019 study in Nature Communications, E. Marie Muehe, a biogeochemist at the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research in Leipzig, Germany, who was then at Stanford University, showed that under future climate conditions, more arsenic will infiltrate rice plants. High arsenic levels boost the health risk of eating the rice and impair plant growth.

Leaching in

When grown in a greenhouse at 5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial temperatures with elevated carbon dioxide levels (representing a future climate), California rice varieties absorbed more of a type of highly toxic arsenic from the soil, raising the rice’s arsenic levels above European Union safety thresholds.

Arsenic levels in rice grains  Credit: E. Otwell Source: E.M. Muehe et al/Nature Comm.2019

Credit: E. Otwell Source: E.M. Muehe et al/Nature Comm.2019

Arsenic naturally occurs in soils, though in most regions the toxic element is present at very low levels. Rice, however, is particularly susceptible to arsenic contamination, because it is grown in flooded conditions. Paddy soils lack oxygen, and the microbes that thrive in this anoxic environment liberate arsenic from the soil. Once the arsenic is in the water, rice plants can draw it in through their roots. From there, the element is distributed throughout the plants’ tissues and grains.

Muehe and her team grew a Californian variety of rice in a local low-arsenic soil inside climate-controlled greenhouses. Increasing the temperature and carbon dioxide levels to match future climate scenarios enhanced the activity of the microbes living in the rice paddy soils and increased the amount of arsenic in the grains, Muehe says. And importantly, rice yields diminished. In the low-arsenic Californian soil under future climate conditions, rice yield dropped 16 percent.

According to the researchers, models that forecast the future production of rice don’t account for the impact of arsenic on harvest yields. What that means, Muehe says, is that current projections are overestimating how much rice will be produced in the future.

Managing rice’s thirst

From atop an embankment that edges one of his fields, Rystrom watches water gush from a pipe, flooding a paddy packed with rice plants. “On a year like this, we decided to pump,” he says.

Able to tap into groundwater, Rystrom left only about 10 percent of his fields unplanted this growing season. “If everybody was pumping from the ground to farm rice every year,” he admits, it would be unsustainable.

One widely studied, drought-friendly method is “alternate wetting and drying,” or intermittent flooding, which involves flooding and draining rice paddies on one- to 10-day cycles, as opposed to maintaining a constant inundation. This practice can cut water use by up to 38 percent without sacrificing yields. It also stabilizes the soil for harvesting and lowers arsenic levels in rice by bringing more oxygen into the soils, disrupting the arsenic-releasing microbes. If tuned just right, it may even slightly improve crop yields.

But the water-saving benefits of this method are greatest when it is used on highly permeable soils, such as those in Arkansas and other parts of the U.S. South, which normally require lots of water to keep flooded, says Bruce Linquist, a rice specialist at the University of California Cooperative Extension. The Sacramento Valley’s clay-rich soils don’t drain well, so the water savings where Rystrom farms are minimal; he doesn’t use the method.

Building embankments, canal systems and reservoirs can also help farmers dampen the volatility of the water cycle. But for some, the solution to rice’s climate-related problems lies in enhancing the plant itself.

Fourth-generation rice farmer Peter Rystrom (left) stands with his grandfather Don Rystrom (middle) and his father Steve Rystrom (right).CALIFORNIA RICE COMMISSION, BRIAN BAER

Fourth-generation rice farmer Peter Rystrom (left) stands with his grandfather Don Rystrom (middle) and his father Steve Rystrom (right).CALIFORNIA RICE COMMISSION, BRIAN BAER

Better breeds

The world’s largest collection of rice is stored near the southern rim of Laguna de Bay in the Philippines, in the city of Los Baños. There, the International Rice Genebank, managed by IRRI, holds over 132,000 varieties of rice seeds from farms around the globe.

Upon arrival in Los Baños, those seeds are dried and processed, placed in paper bags and moved into two storage facilities — one cooled to 2˚ to 4˚ C from which seeds can be readily withdrawn, and another chilled to –20˚ C for long-term storage. To be extra safe, backup seeds are kept at the National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation in Fort Collins, Colo., and the Svalbard Global Seed Vault tucked inside a mountain in Norway.

All this is done to protect the biodiversity of rice and amass a trove of genetic material that can be used to breed future generations of rice. Farmers no longer use many of the stored varieties, instead opting for new higher-yield or sturdier breeds. Nevertheless, solutions to climate-related problems may be hidden in the DNA of those older strains. “Scientists are always looking through that collection to see if genes can be discovered that aren’t being used right now,” says Ronald, of UC Davis. “That’s how Sub1 was discovered.”

Over 132,000 varieties of rice seeds fill the shelves of the climate-controlled International Rice Genebank. Breeders from around the world can use the seeds to develop new climate-resilient rice strains.IRRI/FLICKR (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Over 132,000 varieties of rice seeds fill the shelves of the climate-controlled International Rice Genebank. Breeders from around the world can use the seeds to develop new climate-resilient rice strains.IRRI/FLICKR (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Sub1 gene enables rice plants to endure prolonged periods completely submerged underwater. It was discovered in 1996 in a traditional variety of rice grown in the Indian state of Orissa, and through breeding has been incorporated into varieties cultivated in flood-prone regions of South and Southeast Asia. Sub1-wielding varieties, called “scuba rice,” can survive for over two weeks entirely submerged, a boon for farmers whose fields are vulnerable to flash floods.

Some researchers are looking beyond the genetic variability preserved in rice gene banks, searching instead for useful genes from other species, including plants and bacteria. But inserting genes from one species into another, or genetic modification, remains controversial. The most famous example of genetically modified rice is Golden Rice, which was intended as a partial solution to childhood malnutrition. Golden Rice grains are enriched in beta-carotene, a precursor to vitamin A. To create the rice, researchers spliced a gene from a daffodil and another from a bacterium into an Asian variety of rice.

Three decades have passed since its initial development, and only a handful of countries have deemed Golden Rice safe for consumption. On July 23, the Philippines became the first country to approve the commercial production of Golden Rice. Abdelbagi Ismail, principal scientist at IRRI, blames the slow acceptance on public perception and commercial interests opposed to genetically modified organisms, or GMOs (SN: 2/6/16, p. 22).

Looking ahead, it will be crucial for countries to embrace GM rice, Ismail says. Developing nations, particularly those in Africa that are becoming more dependent on the crop, would benefit greatly from the technology, which could produce new varieties faster than breeding and may allow researchers to incorporate traits into rice plants that conventional breeding cannot. If Golden Rice were to gain worldwide acceptance, it could open the door for new genetically modified climate- and disease-resilient varieties, Ismail says. “It will take time,” he says. “But it will happen.”

Climate change is a many-headed beast, and each rice-growing region will face its own particular set of problems. Solving those problems will require collaboration between local farmers, government officials and the international community of researchers.

“I want my kids to be able to have a shot at this,” Rystrom says. “You have to do a lot more than just farm rice. You have to think generations ahead.”

Climate-resilient rice

To keep rice bowls around the world full, researchers breed new varieties of rice that can endure stresses like drought, floods and salt.

Sahbhagi Dhan: Traditional rice varieties take 120 to 150 days to harvest and require four irrigations. Sahbhagi Dhan is a drought-tolerant variety harvested after 105 days and just two irrigations. In normal conditions, it produces about twice as much rice (four to five metric tons per hectare) as other local varieties in India. Under drought conditions, it produces one to two metric tons per hectare; local varieties produce none.

Scuba rice contains a gene that enables the plant to survive several days underwater, important for areas that experience flooding.IRRI/FLICKR (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Scuba rice contains a gene that enables the plant to survive several days underwater, important for areas that experience flooding.IRRI/FLICKR (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Scuba rice: Sub1, a submergence-tolerance gene, has been bred into scuba rice varieties. Rice normally dies after three to four days of total submergence — many varieties will exhaust themselves to death trying to quickly grow to the water’s surface. Sub1 varieties (shown), however, refrain from this frenzied growth spurt, and can withstand over two weeks underwater, able to survive the sudden floods of the summer monsoon.

Salt-tolerant rice: Made by inserting an area of the genome called Saltol, salt-tolerant rice varieties are better able to regulate the amount of sodium ions, toxic in high amounts, in their tissues. Saltol has been incorporated into high-yield varieties throughout the world.