Between a death and a burial was hardly the best time to show up in a remote village in Madagascar to make a pitch for forest protection. Bad timing, however, turned out to be the easy problem.

This forest was the first one that botanist Armand Randrianasolo had tried to protect. He’s the first native of Madagascar to become a Ph.D. taxonomist at Missouri Botanical Garden, or MBG, in St. Louis. So he was picked to join a 2002 scouting trip to choose a conservation site.

Other groups had already come into the country and protected swaths of green, focusing on “big forests; big, big, big!” Randrianasolo says. Preferably forests with lots of big-eyed, fluffy lemurs to tug heartstrings elsewhere in the world.

The Missouri group, however, planned to go small and to focus on the island’s plants, legendary among botanists but less likely to be loved as a stuffed cuddly. The team zeroed in on fragments of humid forest that thrive on sand along the eastern coast. “Nobody was working on it,” he says.

As the people of the Agnalazaha forest were mourning a member of their close-knit community, Randrianasolo decided to pay his respects: “I wanted to show that I’m still Malagasy,” he says. He had grown up in a seaside community to the north.

The village was filling up with visiting relatives and acquaintances, a great chance to talk with many people in the region. The deputy mayor conceded that after a morning visit to the bereaved, Randrianasolo and MBG’s Chris Birkinshaw could speak in the afternoon with anyone wishing to gather at the roofed marketplace.

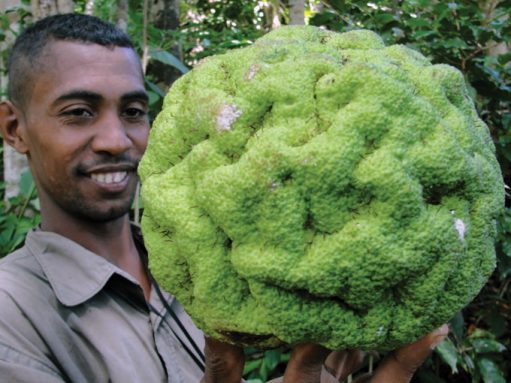

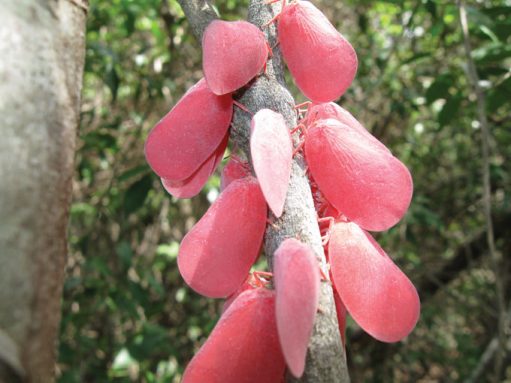

Conserving natural forests is a double win for trapping carbon and saving rich biodiversity. Forests matter to humans (with a Treculia fruit), Phromnia planthoppers and mouse lemurs.

The two scientists didn’t get the reception they’d hoped for. Their pitch to help the villagers conserve their forest while still serving people’s needs met protests from the crowd: “You’re lying!”

Can trees save the world?

Lately, society has been putting a lot of pressure on trees to get us out of the climate change emergency we’re in. There’s no doubt that trees make life better in many respects, but there are right ways and plenty of wrong ways to protect and grow the forests.

- Why planting tons of trees isn’t enough to solve climate change

- Mixing trees and crops can help both farmers and the climate

The community was still upset about a different forest that outside conservationists had protected. The villagers had assumed they would still be able to take trees for lumber, harvest their medicinal plants or sell other bits from the forest during cash emergencies. They were wrong. That place was now off-limits. People caught doing any of the normal things a forest community does would be considered poachers. When MBG proposed conserving yet more land, residents weren’t about to get tricked again. “This is the only forest we have left,” they told the scientists.

Finding some way out of such clashes to save existing forests has become crucial for fighting climate change. Between 2001 and 2019, the planet’s forests trapped an estimated 7.6 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide a year, an international team reported in Nature Climate Change in March. That rough accounting suggests trees may capture about one and a half times the annual emissions of the United States, one of the largest global emitters.

Planting trees by the millions and trillions is basking in round-the-world enthusiasm right now. Yet saving the forests we already have ranks higher in priority and in payoff, say a variety of scientists.

How to preserve forests may be a harder question than why. Success takes strong legal protections with full government support. It also takes a village, literally. A forest’s most intimate neighbors must wholeheartedly want it saved, one generation after another. That theme repeats in places as different as rural Madagascar and suburban New Jersey.

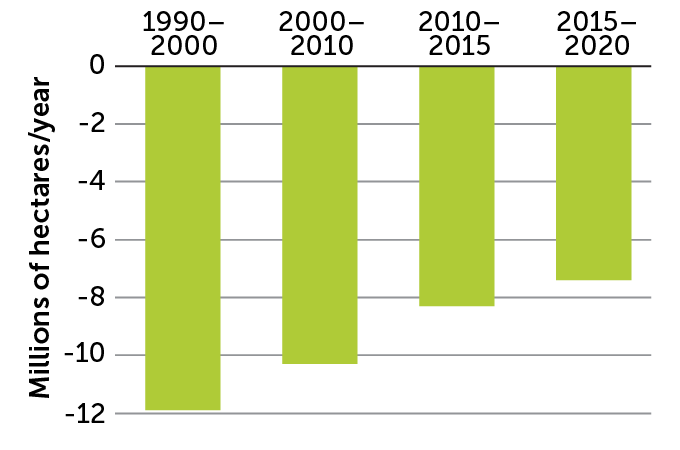

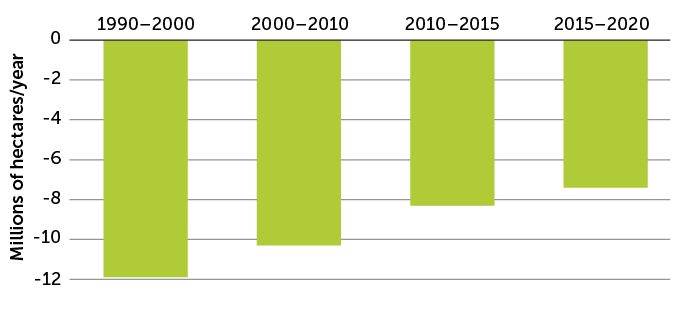

Forest loss down

Destruction of the world’s natural forests continues, though rates have been slowing. The target of two international agreements — to halve the previous decade’s rate by 2020 — has not been met.

C. Chang

C. Chang  C. Chang Source: FAO, 2020

C. Chang Source: FAO, 2020

Overlooked and underprotected

First a word about trees themselves. Of course, trees capture carbon and fight climate change. But trees are much more than useful wooden objects that happen to be leafy, self-manufacturing and great shade for picnics.

“Plant blindness,” as it has been called, reduces trees and other photosynthetic organisms to background, lamented botanist Sandra Knapp in a 2019 article in the journal Plants, People, Planet. For instance, show people a picture with a squirrel in a forest. They’ll likely say something like “cute squirrel.” Not “nice-size beech tree, and is that a young black oak with a cute squirrel on it?”

This tunnel vision also excludes invertebrates, argues Knapp, of the Natural History Museum in London, complicating efforts to save nature. These half-seen forests, natural plus human-planted, now cover close to a third of the planet’s land, according to the 2020 version of The State of the World’s Forests report from the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization. Yet a calculation based on the report’s numbers says that over the last 10 years, net tree cover vanished at an average rate of about 12,990 hectares — a bit more than the area of San Francisco — every day.

This is an improvement over the previous decades, the report notes. In the 1990s, deforestation, on average, destroyed about 1.75 San Francisco equivalents of forest every day.

Branches of a Dracaena cinnabari dragon’s blood tree from Yemen ooze red sap and repeatedly bifurcate in even Y-splits.BORIS KHVOSTICHENKO/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Branches of a Dracaena cinnabari dragon’s blood tree from Yemen ooze red sap and repeatedly bifurcate in even Y-splits.BORIS KHVOSTICHENKO/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Trees were the planet’s skyscrapers, many rising to great heights, hundreds of millions of years before humans began piling stone upon stone to build their own. Trees reach their stature by growing and then killing their innermost core of tissue. The still-living outer rim of the tree uses its ever-increasing inner ghost architecture as plumbing pipes that can function as long as several human lifetimes. And tree sex lives, oh my. Plants invented “steamy but not touchy” long before the Victorian novel — much flowering, perfuming and maybe green yearning, all without direct contact of reproductive organs. Just a dusting of pollen wafted on a breeze or delivered by a bee.

To achieve the all-important goal of cutting global emissions, saving the natural forests already in the ground must be a priority, 14 scientists from around the world wrote in the April Global Change Biology. “Protect existing forests first,” coauthor Kate Hardwick of Kew Gardens in London said during a virtual conference on reforestation in February. That priority also gives the planet’s magnificent biodiversity a better chance at surviving. Trees can store a lot of carbon in racing to the sky. And size and age matter because trees add carbon over so much of their architecture, says ecologist David Mildrexler with Eastern Oregon Legacy Lands at the Wallowology Natural History Discovery Center in Joseph. Trees don’t just start new growth at twigs tipped with unfurling baby leaves. Inside the branches, the trunk and big roots, an actively growing sheath surrounds the inner ghost plumbing. Each season, this whole sheath adds a layer of carbon-capturing tissue from root to crown.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

“Imagine you’re standing in front of a really big tree — one that’s so big you can’t even wrap your arms all the way around, and you look up the trunk,” Mildrexler says. Compare that sky-touching vision to the area covered in a year’s growth of some sapling, maybe three fingers thick and human height. “The difference is, of course, just huge,” he says.

Big trees may not be common, but they make an outsize difference in trapping carbon, Mildrexler and colleagues have found. In six Pacific Northwest national forests, only about 3 percent of all the trees in the study, including ponderosa pines, western larches and three other major species, reached full-arm-hug size (at least 53.3 centimeters in diameter). Yet this 3 percent of trees stored 42 percent of the aboveground carbon there, the team reported in 2020 in Frontiers in Forests and Global Change. An earlier study, with 48 sites worldwide and more than 5 million tree trunks, found that the largest 1 percent of trees store about 50 percent of the aboveground carbon-filled biomass.

Plant paradise

The island nation of Madagascar was an irresistible place for the Missouri Botanical Garden to start trying to conserve forests. Off the east coast of Africa, the island stretches more than the distance from Savannah, Ga., to Toronto, and holds more than 12,000 named species of trees, other flowering plants and ferns. Madagascar “is absolute nirvana,” says MBG botanist James S. Miller, who has spent decades exploring the island’s flora.

The Ravenala traveler’s tree is widely grown, but native only to Madagascar.CEPHOTO, UWE ARANAS/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Ravenala traveler’s tree is widely grown, but native only to Madagascar.CEPHOTO, UWE ARANAS/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Just consider the rarities. Of the eight known species of baobab trees, which raise a fat trunk to a cartoonishly spindly tuft of little branches on top, six are native to Madagascar. Miller considers some 90 percent of the island’s plants as natives unique to the country. “It wrecks you” for botanizing elsewhere, Miller says.

He was rooting for his MBG colleagues Randrianasolo and Birkinshaw in their foray to Madagascar’s Agnalazaha forest. Several months after getting roasted as liars by residents, the two got word that the skeptics had decided to give protection a chance after all.

The Agnalazaha residents wanted to make sure, however, that the Missouri group realized the solemnity of their promise. Randrianasolo had to return to the island for a ceremony of calling the ancestors as witnesses to the new partnership and marking the occasion with the sacrifice of a cow. A pact with generations of deceased residents may be an unusual form of legal involvement, but it carried weight. Randrianasolo bought the cow.

Randrianasolo looked for ways to be helpful. MBG worked on improving the village’s rice yields, and supplied starter batches of vegetable seeds for expanding home gardens. The MBG staff helped the forest residents apply for conservation funds from the Malagasy government. A new tree nursery gave villagers an alternative to cutting timber in the forest. The nursery also meant some jobs for local people, which further improved relationships.

Trying to build trust with people living near southeastern Madagascar’s coast was the first task the Missouri Botanical Garden faced in efforts to conserve the Agnalazaha forest.Courtesy of the staff of the Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis and Madagascar

Trying to build trust with people living near southeastern Madagascar’s coast was the first task the Missouri Botanical Garden faced in efforts to conserve the Agnalazaha forest.Courtesy of the staff of the Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis and Madagascar

The MBG staff now works with Malagasy communities to preserve forests at 11 sites dotted in various ecosystems in Madagascar. Says Randrianasolo: “You have to be patient.”

Today, 19 years after his first visit among the mourners, Agnalazaha still stands.

Saving forests is not a simple matter of just meeting basic needs of people living nearby, says political scientist Nadia Rabesahala Horning of Middlebury College in Vermont, who published The Politics of Deforestation in Africa in 2018. Her Ph.D. work, starting in the late 1990s, took her to four remote forests in her native Madagascar. The villagers around each forest followed different rules for harvesting timber, finding places to graze livestock and collecting medicinal plants.

Three of the forests shrank, two of them rapidly, over the decade. One, called Analavelona, however, barely showed any change in the aerial views Horning used to look for fraying forests.

Near Madagascar’s Analavelona sacred forest, taxonomist Armand Randrianasolo (blue cap) joins (from left) Miandry Fagnarena, Rehary, and Tefy Andriamihajarivo to collect a surprising new species in the mango family (green leaves at front of image). The Spondias tefyi, named for Tefy and his efforts to protect the island’s biodiversity, is the first wild relative of the popular hog plum found outside of South America or Asia.Courtesy of the staff of the Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis and Madagascar

Near Madagascar’s Analavelona sacred forest, taxonomist Armand Randrianasolo (blue cap) joins (from left) Miandry Fagnarena, Rehary, and Tefy Andriamihajarivo to collect a surprising new species in the mango family (green leaves at front of image). The Spondias tefyi, named for Tefy and his efforts to protect the island’s biodiversity, is the first wild relative of the popular hog plum found outside of South America or Asia.Courtesy of the staff of the Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis and Madagascar

The people living around Analavelona revered it as a sacred place where their ancestors dwelled. Living villagers made offerings before entering, and cut only one kind of tree, which they used for coffins.

Since then, Horning’s research in Tanzania and Uganda has convinced her that forest conservation can happen only under very specific conditions, she says. The local community must be able to trust that the government won’t let some commercial interest or a political heavyweight slip through loopholes to exploit a forest that its everyday neighbors can’t touch. And local people must be able to meet their own needs too, including the spiritual ones.

A different kind of essential

Tied with yarn to nearly 3,000 trees in a Maryland forest, tags displayed the names of the people lost on 9/11. The memorial, organized by ecologist Joan Maloof who runs the Old-Growth Forest Network, helped protect a patch of woods where people could go for solace and meditation.Friends of the Forest, Salisbury

Tied with yarn to nearly 3,000 trees in a Maryland forest, tags displayed the names of the people lost on 9/11. The memorial, organized by ecologist Joan Maloof who runs the Old-Growth Forest Network, helped protect a patch of woods where people could go for solace and meditation.Friends of the Forest, Salisbury

Another constellation of old forests, on the other side of the world, sports some less-than-obvious similarities. Ecologist Joan Maloof launched the Old-Growth Forest Network in 2011 to encourage people to save the remaining scraps of U.S. old-growth forests. Her bold idea: to permanently protect one patch of old forest in each of the more than 2,000 counties in the United States where forests can grow.

She calls for strong legal measures, such as conservation easements that prevent logging, but also recognizes the need to convey the emotional power of communing with nature. One of the early green spots she and colleagues campaigned for was not old growth, but it had become one of the few left unlogged where she lived on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

She heard about Buddhist monks in Thailand who had ordained trees as monks because loggers revered the monks, so the trees were protected. A month after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, she was inspired to turn the Maryland forest into a place to remember the victims. By putting each victim’s name on a metal tag and tying it to a tree, she and other volunteers created a memorial with close to 3,000 trees. The local planning commission, she suspected, would feel awkward about approving timber cutting from that particular stand. She wasn’t party to their private deliberations, but the forest still stands.

In 1973, high school freshman Doug Hefty wrote more than 80 pages about the value of Saddler’s Woods in Haddon Township, N.J. His typed report, with its handmade cover, played a dramatic role in saving the forest. Saddler’s Woods Conservation Association

In 1973, high school freshman Doug Hefty wrote more than 80 pages about the value of Saddler’s Woods in Haddon Township, N.J. His typed report, with its handmade cover, played a dramatic role in saving the forest. Saddler’s Woods Conservation Association

As of Earth Day 2021, the network had about 125 forests around the country that should stay forests in perpetuity. Their stories vary widely, but are full of local history and political maneuvering.

In southern New Jersey, Joshua Saddler, an escaped enslaved man from Maryland, acquired part of a small forest in the mid-1880s and bequeathed it to his wife with the stipulation that it not be logged. His section was logged anyway, and the rest of the original old forest was about to meet the same fate. In 1973, high school student Doug Hefty wrote more than 80 pages on the forest’s value — and delivered it to the developer. In this case, life delivered a genuine Hollywood ending. The developer relented, and scaled back the project, stopping across the street from the woods.

In 1999, however, developers once again eyed the forest, says Janet Goehner-Jacobs, who heads the Saddler’s Woods Conservation Association. It took four years, but now, she and the forests’ other fans have a conservation easement forbidding commercial development or logging, giving the next generation better tools to protect the forest.

Goehner-Jacobs had just moved to the area and fallen in love with that 10-hectare patch of green in the midst of apartment buildings and strip malls. When she first happened upon the forest and found the old-growth section, “I just instinctively knew I was seeing something very different.”

Saddler’s Woods, with a scrap of old-growth forest, has survived in the rush of development in suburban New Jersey thanks to generations of dedicated forest lovers.Saddler’s Woods Conservation Association

Saddler’s Woods, with a scrap of old-growth forest, has survived in the rush of development in suburban New Jersey thanks to generations of dedicated forest lovers.Saddler’s Woods Conservation Association