On most mornings, Jeremy D. Brown eats an avocado. But first, he gives it a little squeeze. A ripe avocado will yield to that pressure, but not too much. Brown also gauges the fruit’s weight in his hand and feels the waxy skin, with its bumps and ridges.

“I can’t imagine not having the sense of touch to be able to do something as simple as judging the ripeness of that avocado,” says Brown, a mechanical engineer who studies haptic feedback — how information is gained or transmitted through touch — at Johns Hopkins University.

Many of us have thought about touch more than usual during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hugs and high fives rarely happen outside of the immediate household these days. A surge in online shopping has meant fewer chances to touch things before buying. And many people have skipped travel, such as visits to the beach where they might sift sand through their fingers. A lot goes into each of those actions.

“Anytime we touch anything, our perceptual experience is the product of the activity of thousands of nerve fibers and millions of neurons in the brain,” says neuroscientist Sliman Bensmaia of the University of Chicago. The body’s natural sense of touch is remarkably complex. Nerve receptors detect cues about pressure, shape, motion, texture, temperature and more. Those cues cause patterns of neural activity, which the central nervous system interprets so we can tell if something is smooth or rough, wet or dry, moving or still.

Scientists at the University of Chicago attached strips of different materials to a rotating drum to measure vibrations produced in the skin as a variety of textures move across a person’s fingertips. Matt Wood/Univ. of Chicago

Scientists at the University of Chicago attached strips of different materials to a rotating drum to measure vibrations produced in the skin as a variety of textures move across a person’s fingertips. Matt Wood/Univ. of Chicago

Neuroscience is at the heart of research on touch. Yet mechanical engineers like Brown and others, along with experts in math and materials science, are studying touch with an eye toward translating the science into helpful applications. Researchers hope their work will lead to new and improved technologies that mimic tactile sensations.

As scientists and engineers learn more about how our nervous system responds to touch stimuli, they’re also studying how our skin interacts with different materials. And they’ll need ways for people to send and receive simulated touch sensations. All these efforts present challenges, but progress is happening. In the near term, people who have lost limbs might recover some sense of touch through their artificial limbs. Longer term, haptics research might add touch to online shopping, enable new forms of remote medicine and expand the world of virtual reality.

“Anytime you’re interacting with an object, your skin deforms,” or squishes a bit.

Sliman Bensmaia

Good vibrations

Virtual reality programs already give users a sense of what it’s like to wander through the International Space Station or trek around a natural gas well. For touch to be part of such experiences, researchers will need to reproduce the signals that trigger haptic sensations.

Our bodies are covered in nerve endings that respond to touch, and our hands are really loaded up, especially our fingertips. Some receptors tell where parts of us are in relation to the rest of the body. Others sense pain and temperature. One goal for haptics researchers is to mimic sensations resulting from force and movement, such as pressure, sliding or rubbing.

“Anytime you’re interacting with an object, your skin deforms,” or squishes a bit, Bensmaia explains. Press on the raised dots of a braille letter, and the dots will poke your skin. A soapy glass slipping through your fingers produces a shearing force — and possibly a crash. Rub fabric between your fingers, and the action produces vibrations.

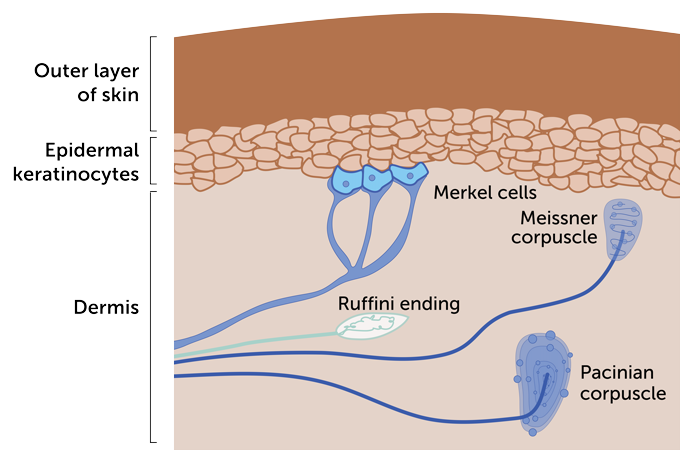

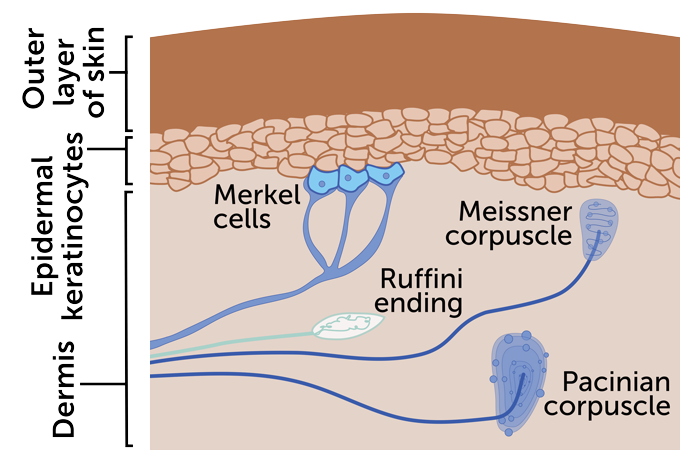

Four main categories of touch receptors respond to those and other mechanical stimuli. There’s some overlap among the types. And a single contact with an object can affect multiple types of receptors, Bensmaia notes.

One type, called Pacinian corpuscles, sits deep in the skin. They are especially good at detecting vibrations created when we interact with different textures. When stimulated, the receptors produce sequences of signals that travel to the brain over a period of time. Our brains interpret the signals as a particular texture. Bensmaia compares it to the way we hear a series of notes and recognize a tune.

Deep feelings

Four main types of touch receptors respond to mechanical stimulation of the skin: Meissner corpuscles, Merkel cells, Ruffini endings and Pacinian corpuscles. Some respond better to certain kinds of stimuli than others. Recent studies have focused on the deep-skin Pacinian corpuscles, which respond to vibrations created when fingers rub against textured materials.

T. Tibbitts

T. Tibbitts  T. Tibbitts Source: Scholarpedia.org

T. Tibbitts Source: Scholarpedia.org

“Corduroy will produce one set of vibrations. Organza will produce another set,” Bensmaia says. Each texture produces “a different set of vibrations in your skin that we can measure.” Such measurements are a first step toward trying to reproduce the feel of different textures.

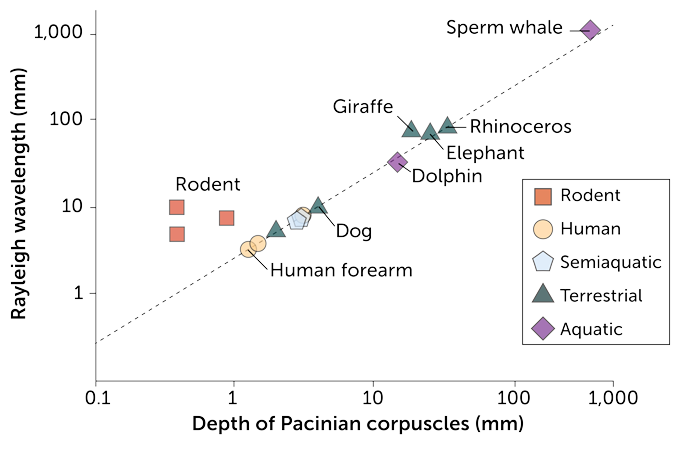

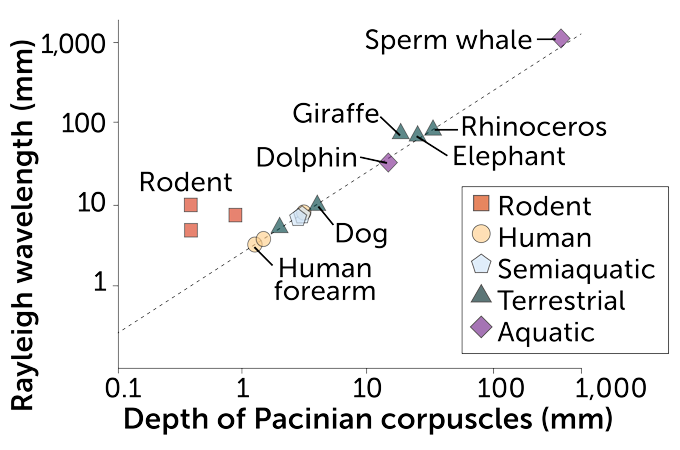

Additionally, any stimulus meant to mimic a texture sensation must be strong enough to trigger responses in the nervous system’s touch receptors. That’s where work by researchers at the University of Birmingham in England comes in. The vibrations from contact with various textures create different kinds of wave energy. Rolling-type waves called Rayleigh waves go deep enough to reach the Pacinian receptors, the team reported last October in Science Advances. Much larger versions of the same types of waves cause much of the damage from earthquakes.

Not all touches are forceful enough to trigger a response from the Pacinian receptors. To gain more insight into which interactions will stimulate those receptors, the team looked at studies that have collected data on touches to the limbs, head or neck of dogs, dolphins, rhinos, elephants and other mammals. A pattern emerged. The group calls it a “universal scaling law” of touch for mammals.

For the most part, a touch at the surface will trigger a response in a Pacinian receptor deep in the skin if the ratio is 5-to-2 between the length of the Rayleigh waves resulting from the touch and the depth of the receptor. At that ratio or higher, a person and most other mammals will feel the sensation, says mathematician James Andrews, lead author of the study.

Universality of touch

A pattern in the ratio of length of Rayleigh waves moving through skin while touching an object and the depth of Pacinian touch receptors suggests that the same amount of deformation in the skin of several different mammals, except rodents, will produce similar sensations.

Ratio of Rayleigh wavelength to touch receptor depth in various mammals  T. Tibbitts

T. Tibbitts  T. Tibbitts Source: J. Andrews et al/Science Advances 2020

T. Tibbitts Source: J. Andrews et al/Science Advances 2020

Also, the amount of skin displacement needed to cause wavelengths long enough to trigger a sensation by the Pacinian receptors will be the same across most mammal species, the group found. Different species will need more or less force to cause that displacement, however, which may depend on skin composition or other factors. Rodents did not fit the 5–2 ratio, perhaps because their paws and limbs are so small compared with the wavelengths created when they touch things, Andrews notes.

Beyond that, the work sheds light on “what types of information you’d need to realistically capture the haptic experience — the touch experience — and send that digitally anywhere,” Andrews says. People could then feel sensations with a device or perhaps with ultrasonic waves. Someday the research might help provide a wide range of virtual reality experiences, including virtual hugs.

Online tactile shopping

Mechanical engineer Cynthia Hipwell of Texas A&M University in College Station moved into a new house before the pandemic. She looked at some couches online but couldn’t bring herself to buy one from a website. “I didn’t want to choose couch fabric without feeling it,” Hipwell says.

“Ideally, in the long run, if you’re shopping on Amazon, you could feel fabric,” she says. Web pages’ computer codes would make certain areas on a screen mimic different textures, perhaps with shifts in electrical charge, vibration signals, ultrasound or other methods. Touching the screen would clue you in to whether a sweater is soft or scratchy, or if a couch’s fabric feels bumpy or smooth. Before that can happen, researchers need to understand conditions that affect our perception of how a computer screen feels.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Surface features at the nanometer scale (billionths of a meter) can affect how we perceive the texture of a piece of glass, Hipwell says. Likewise, we may not consciously feel any wetness as humidity in the air mixes with our skin’s oil and sweat. But tiny changes in that moisture can alter the friction our fingers encounter as they move on a screen, she says. And that friction can influence how we perceive the screen’s texture.

Shifts in electric charge also can change the attraction between a finger and a touch screen. That attraction is called electroadhesion, and it affects our tactile experience as we touch a screen. Hipwell’s group recently developed a computer model that accounts for the effects of electroadhesion, moisture and the deformation of skin pressing against glass. The team reported on the work in March 2020 in IEEE Transactions on Haptics.

Hipwell hopes the model can help product designers develop haptic touch screens that go beyond online shopping. A car’s computerized dashboard might have sections that change texture for each menu, she suggests. A driver could change temperature or radio settings by touch while keeping eyes on the road.

“Ideally, in the long run, if you’re shopping on Amazon, you could feel fabric.”

Cynthia Hipwell

Wireless touch patches

Telemedicine visits rose dramatically during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. But video doesn’t let doctors feel for swollen glands or press an abdomen to check for lumps. Remote medicine with a sense of touch might help during pandemics like this one — and long after for people in remote areas with few doctors.

People in those places might eventually have remote sensing equipment in their own homes or at a pharmacy or workplace. If that becomes feasible, a robot, glove or other equipment with sensors could touch parts of a patient’s body. The information would be relayed to a device somewhere else. A doctor at that other location could then experience the sensations of touching the patient.

Researchers are already working on materials that can translate digital information about touch into sensations people — in this case, doctors — can feel. The same materials could communicate information for virtual reality applications. One possibility is a skin patch developed by physical chemist John Rogers of Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., and others.

One layer of the flexible patch sticks to a person’s skin. Other layers include a stretchable circuit board and tiny actuators that create vibrations as current flows around them. Wireless signals tell the actuators to turn on or off. Energy to run the patch also comes in wirelessly. The team described the patch in Nature in 2019.

Retired U.S. Army Sgt. Garrett Anderson shakes hands with researcher Aadeel Akhtar, CEO of Psyonic, a prosthesis developer. A wireless skin patch on Anderson’s upper arm gives him sensory feedback when grasping an object.Northwestern Univ.

Retired U.S. Army Sgt. Garrett Anderson shakes hands with researcher Aadeel Akhtar, CEO of Psyonic, a prosthesis developer. A wireless skin patch on Anderson’s upper arm gives him sensory feedback when grasping an object.Northwestern Univ.  Inside the patch are circular actuators that vibrate in response to signals. The prototype device might give the sensation of touch pressure in artificial limbs, in virtual reality and telemedicine. Northwestern Univ.

Inside the patch are circular actuators that vibrate in response to signals. The prototype device might give the sensation of touch pressure in artificial limbs, in virtual reality and telemedicine. Northwestern Univ.

Since then, Rogers’ group has reduced the patch’s thickness and weight. The patch now also provides more detailed information to a wearer. “We have scaled the systems into a modular form to allow custom sizes [and] shapes in a kind of plug-and-play scheme,” Rogers notes. So far, up to six separate patches can work at the same time on different parts of the body.

The group also wants to make its technology work with electronics that many consumers have, such as smartphones. Toward that end, Rogers and colleagues have developed a pressure-sensitive touch screen interface for sending information to the device. The interface lets someone provide haptic sensations by moving their fingers on a smartphone or touch screen–based computer screen. A person wearing the patch then feels stroking, tapping or other touch sensations.

Pressure points

Additionally, Rogers’ team has developed a way to use the patch system to pick up signals from pressure on a prosthetic arm’s fingertips. Those signals can then be relayed to a patch worn by the person with the artificial limb. Other researchers also are testing ways to add tactile feedback to prostheses. European researchers reported in 2019 that adding feedback for pressure and motion helped people with an artificial leg walk with more confidence (SN: 10/12/19, p. 8). The device reduced phantom limb pain as well.

Brown, the mechanical engineer at Johns Hopkins, hopes to help people control the force of their artificial limbs. Nondisabled people adjust their hands’ force instinctively, he notes. He often takes his young daughter’s hand when they’re in a parking lot. If she starts to pull away, he gently squeezes. But he might easily hurt her if he couldn’t sense the stiffness of her flesh and bones.

Two types of prosthetic limbs can let people who lost an arm do certain movements again. Hands on “body-controlled” limbs open or close when the user moves other muscle groups. The movement works a cable on a harness that connects to the hand. Force on those other muscles tells the person if the hand is open or closed. Myoelectric prosthetic limbs, in contrast, are directly controlled by the muscles on the residual limb. Those muscle-controlled electronic limbs generally don’t give any feedback about touch. Compared with the body-controlled options, however, they allow a greater range of motion and can offer other advantages.

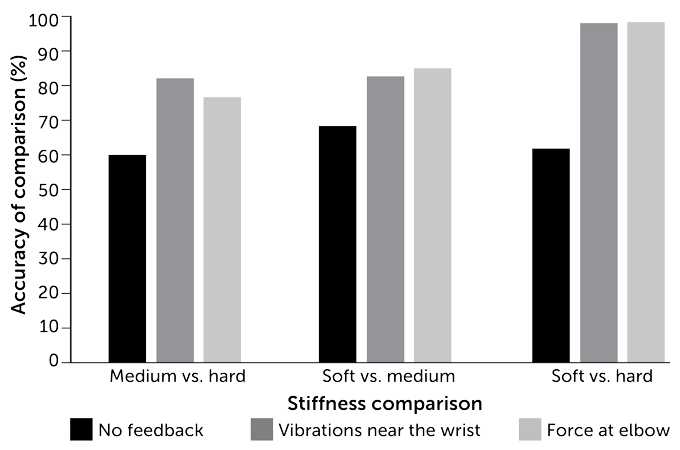

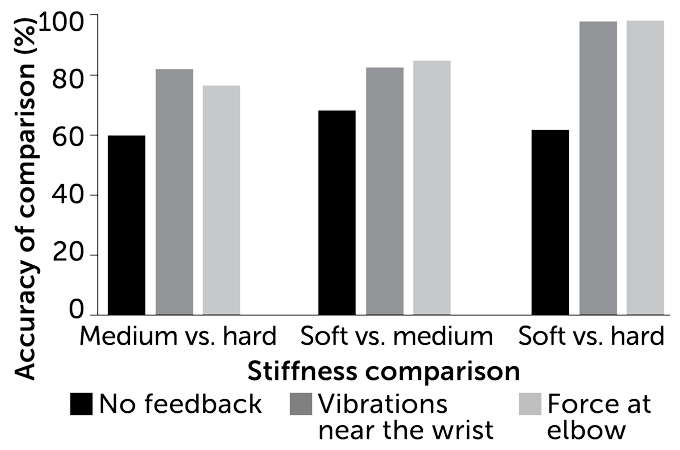

In one study, Brown’s group tested two ways to add feedback about the force that a muscle-controlled electronic limb exerts on an object. One method used an exoskeleton that applied force around a person’s elbow. The other technique used a device strapped near the wrist. The stiffer an object is, the stronger the vibrations on someone’s wrist. Volunteers without limb loss tried using each setup to judge the stiffness of blocks.

In a study of two different haptic feedback methods, one system applied force near the elbow. N. Thomas et al/J. NeuroEng. Rehab. 2019

In a study of two different haptic feedback methods, one system applied force near the elbow. N. Thomas et al/J. NeuroEng. Rehab. 2019  The other system tested in the study provided vibrations near the wrist. N. Thomas et al/J. NeuroEng. Rehab. 2019

The other system tested in the study provided vibrations near the wrist. N. Thomas et al/J. NeuroEng. Rehab. 2019

Both methods worked better than no feedback. And compared with each other, the two types of feedback “worked equally well,” Brown says. “We think that is because, in the end, what the human user is doing is creating a map.” Basically, people match up how much force corresponds to the intensity of each type of feedback. The work suggests ways to improve muscle-controlled electronic limbs, Brown and colleagues reported in 2019 in the Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation.

Helpful feedback

Volunteers without limb loss wore an artificial lower arm with and without different types of haptic feedback: one at the elbow and one at the wrist. Participants compared the softness or hardness of different blocks. Both types of feedback improved participants’ accuracy in judging stiffness over the tests with no feedback.

The impact of feedback on accuracy of sensing block stiffness  T. Tibbitts

T. Tibbitts  T. Tibbitts Source: N. Thomas et al/J. NeuroEng. Rehab. 2019

T. Tibbitts Source: N. Thomas et al/J. NeuroEng. Rehab. 2019

Still, people’s brains may not be able to match up all types of feedback for touch sensations. Bensmaia’s group at the University of Chicago has worked with colleagues in Sweden who built tactile sensors into bionic hands: Signals from a sensor on the thumb went to an electrode implanted around the ulnar nerve on people’s arms. Three people who had lost a hand tested the bionic hands and felt a touch when the thumb was prodded, but the touch felt as if it came from somewhere else on the hand.

Doctors can choose which nerve an electrode will stimulate. But they don’t know in advance which bundle of fibers it will affect within the nerve, Bensmaia explains. And different bundles receive and supply sensations to different parts of the hand. Even after the people had used the prosthesis for more than a year, the mismatch didn’t improve. The brain didn’t adapt to correct the sensation. The team shared its findings last December in Cell Reports.

Despite that, in previous studies, those same people using the bionic hands had better precision and more control over their force when grasping objects, compared with those using versions without direct stimulation of the nerve. People getting the direct nerve stimulation also reported feeling as if the hand was more a part of them.

As with the bionic hands, advances in haptic technology probably won’t start out working perfectly. Indeed, virtual hugs and other simulated touch experiences may never be as good as the real thing. Yet haptics may help us get a feel for the future, with new ways to explore our world and stay in touch with those we love.