For the first time, a spacecraft is headed to Jupiter’s odd Trojan asteroids. What Lucy finds there could provide a fresh peek into the history of the solar system.

“Lucy will profoundly change our understanding of planetary evolution in our solar system,” Adriana Ocampo, a planetary scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., said at a news briefing October 14.

The mission is set to launch from the Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral, Fla., as early as October 16. Live coverage will air on NASA TV beginning at 5 a.m. EDT, in anticipation of a 5:34 a.m. blast off.

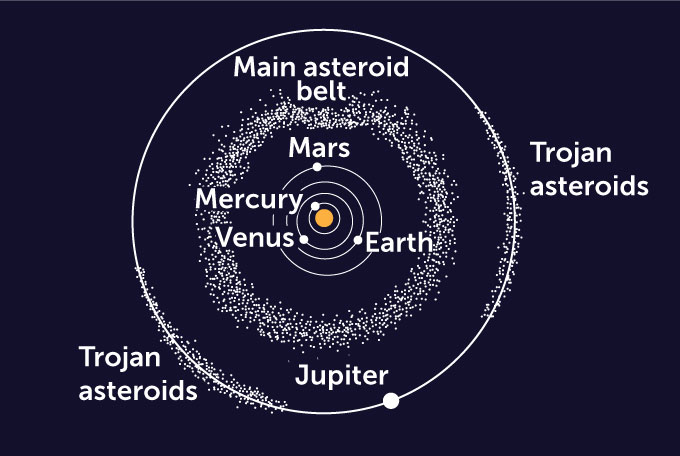

The Trojan asteroids are two groups of space rocks that are gravitationally trapped in the same orbit as Jupiter around the sun. One group of Trojans orbits ahead of Jupiter; the other follows the gas giant around the sun. Planetary scientists think the Trojans could have formed at different distances from the sun before getting mixed together in their current homes. The asteroids could also be some of the oldest and most pristine objects in the solar system.

The mission will mark several other firsts, from the types of objects it will visit to the way it powers its instruments. Here are five cool things to know about our first visit to the Trojans.

1. The Trojan asteroids are a solar system time capsule.

The Trojans occupy spots known as Lagrangian points, where the gravity from the sun and from Jupiter effectively cancel each other out. That means their orbits are stable for billions of years.

“They were probably placed in their orbits by the final gasp of the planet formation process,” the mission’s principal investigator Hal Levison, a planetary scientist at Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., said September 28 in a news briefing.

But that doesn’t mean the asteroids are all alike. Scientists can tell from Earth that some Trojans are gray and some are red, indicating that they might have formed in different places before settling in their current orbits. Maybe the gray ones formed closer to the sun, and the red ones formed farther from the sun, Levison speculated.

Studying the Trojans’ similarities and differences can help planetary scientists tease out whether and when the giant planets moved around before settling into their present positions (SN: 4/20/12). “This is telling us something really fundamental about the formation of the solar system,” Levison said.

2. The spacecraft will visit more individual objects than any other single spacecraft.

Lucy will visit eight asteroids, including their moons. Over its 12-year mission, it will visit one asteroid in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and seven Trojans, two of which are binary systems where a pair of asteroids orbit each other.

“We are going to be visiting the most asteroids ever with one mission,” planetary scientist Cathy Olkin, Lucy’s deputy principal investigator, said in the Oct. 14 briefing.

The spacecraft will observe the asteroids’ composition, shape, gravity and geology for clues to where they formed and how they got to the Lagrangian points.

The spacecraft’s first destination, in April 2025, will be an asteroid in the main belt. Next, it will visit five asteroids in the group of Trojans that orbit the sun ahead of Jupiter: Eurybates and its satellite Queta in August 2027; Polymele in September 2027; Leucus in April 2028; and Orus in November 2028. Finally, the spacecraft will shift to Jupiter’s other side and visit the twin asteroids Patroclus and Menoetius in the trailing group of space rocks in March 2033.

The spacecraft won’t land on any of its targets, but it will swoop within 965 kilometers of their surfaces at speeds of 3 to 5 meters per second relative to the asteroids’ speed through space.

There’s no need to worry about collisions while zipping through these asteroid clusters, Levison said. Although there are about 7,000 known Trojans, they’re very far apart. “If you were standing on any one of our targets, you wouldn’t be able to tell you were part of the swarm,” he said.

The Trojan asteroids trail and follow Jupiter in its orbit around the sun, but they’re actually quite far from the giant planet. In fact, Earth is closer to Jupiter than either swarm of Trojans is.NASA, adapted by T. TibbittsThe Trojan asteroids trail and follow Jupiter in its orbit around the sun, but they’re actually quite far from the giant planet. In fact, Earth is closer to Jupiter than either swarm of Trojans is.NASA, adapted by T. Tibbitts

The Trojan asteroids trail and follow Jupiter in its orbit around the sun, but they’re actually quite far from the giant planet. In fact, Earth is closer to Jupiter than either swarm of Trojans is.NASA, adapted by T. TibbittsThe Trojan asteroids trail and follow Jupiter in its orbit around the sun, but they’re actually quite far from the giant planet. In fact, Earth is closer to Jupiter than either swarm of Trojans is.NASA, adapted by T. Tibbitts

3. Lucy will have a weird flight path.

In order to make so many stops, Lucy will need to take a complex path. First, the spacecraft will swoop past Earth twice to get a gravitational boost from our planet that will help propel it onward to its first asteroid.

The closest Earth flyby, in October 2022, will take it within 300 kilometers of the planet’s surface, closer than the International Space Station, the Hubble Space Telescope and many satellites, Olkin said. Observers on Earth might even be able to see it. “I’m hoping to go near where it flies past and look up and see Lucy flying by a year from now,” she said.

Then in December 2030, after more than a year exploring the “leading” swarm of Trojans, Lucy will come back to the vicinity of Earth for one more boost. That final gravitational slingshot will send the spacecraft to the other side of the sun to visit the “trailing” swarm. This will make Lucy the first spacecraft ever to venture to the outer solar system and come back near Earth again.

4. Lucy will travel farther from the sun than any other solar-powered craft.

Another record Lucy will break has to do with its power source: the sun. Lucy will run on solar power out to 850 million kilometers away from the sun, making it the farthest-flung solar powered spacecraft ever.

To accomplish that, Lucy has a pair of enormous solar arrays. Each 10-sided array is more than 7.3 meters across and includes about 4,000 solar cells per panel, Lucy project manager Donya Douglas-Bradshaw said in a news briefing on October 13. Standing on one end, Lucy and its solar panels would be as tall as a five-story building.

“It’s a very intricate, sophisticated design,” she said. The advantage of using solar power is that the team can adjust how much power the spacecraft needs based on how far from the sun it is.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

5. The inspiration for Lucy’s name is decidedly earthbound.

NASA missions are often named for famous scientists, or with acronyms that describe what the mission will do. Lucy, on the other hand, is named after a fossil.

The idea that the Trojans hold secrets to the history of the solar system is part of how the mission got its unusual name. To understand, go back to 1974, when paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson and a graduate student discovered a fossil of a human ancestor who had lived 3.2 million years ago. After listening to the Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” at camp that night, Johanson’s team named the fossil hominid “Lucy.” (In a poetic echo, the first asteroid the Lucy spacecraft will visit is named Donaldjohanson.)

Planetary scientists hope the study of the Trojans will revolutionize our understanding of the solar system’s history in the same way that studying Lucy’s fossil revolutionized our understanding of human history.

“We think these asteroids are fossils of solar system formation,” Levison said. So his team named the spacecraft after the fossil.

The spacecraft even carries a diamond in one of its instruments, to help split beams of light. Said planetary scientist Phil Christensen of Arizona State University in Tempe at the Oct. 14 briefing: “We truly are sending a diamond into the sky with Lucy.”