Researchers at Swinburne University of Technology have contributed to a landmark study that complicates our understanding of the universe.

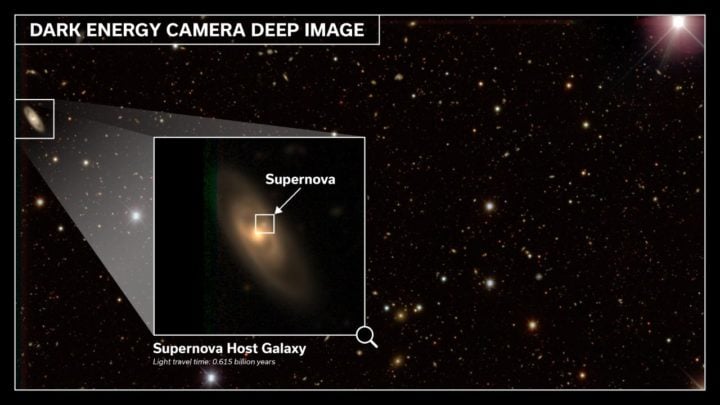

An example of a supernova discovered by the Dark Energy Survey within the field covered by one of the individual detectors in the Dark Energy Camera. The supernova exploded in a spiral galaxy with redshift = 0.04528, about 0.6 billion years light years away. This is one of the nearest supernovae in the sample. In the inset, the supernova is a small dot at the upper-right of the bright galaxy center. Image credit: DES collaboration

The Dark Energy Survey (DES) represents the work of over 400 astrophysicists, astronomers and cosmologists from over 25 institutions.

DES scientists took data for 758 nights across six years to understand the nature of dark energy and measure the universe’s expansion rate. According to a new complex theory, the density of dark energy in the universe could have varied over time.

Dr Anais Möller from Swinburne University of Technology’s Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing was part of the team working on this revolutionary analysis, alongside Swinburne’s Mitchell Dixon, Professor Karl Glazebrook and Emeritus Professor Jeremy Mould.

“These results, a collaboration between hundreds of scientists around the world, are a testament to power of cooperation and hard work to make major scientific progress,” says Dr Möller.

“I am very proud of the work we have achieved as a team; it is an incredibly thorough analysis which reduces our uncertainties to new levels and shows the power of the Dark Energy Survey.”

“We not only used state-of-the-art data, but also developed pioneering methods to extract the maximum information from the Supernova Survey. I am particularly proud of this, as I developed the method to select the supernovae used for the survey with machine learning.”

In 1998, astrophysicists discovered that the universe is accelerating, attributed to a mysterious entity called dark energy that makes up about 70 per cent of our universe. At the time, astrophysicists agreed that the universe’s expansion should be slowing down because of gravity.

This revolutionary discovery, which astrophysicists achieved with observations of specific kinds of exploding stars, called type Ia (read “type one-A”) supernovae, was recognized with the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2011.

Now, 25 years after the initial discovery, the Dark Energy Survey is a culmination of a decade’s worth of research from scientists worldwide who analysed more than 1,500 supernovas using the strongest constraints on the expansion of the universe ever obtained. This is largest number of type Ia supernovae ever used for constraining dark energy from a single survey probing large cosmic times.

The outcome results are consistent with the now-standard cosmological model of a universe with an accelerated expansion. Yet, the findings are not definitive enough to rule out a possibly more complex model.

“There is still so much to discover about dark energy, but this analysis can be considered as the gold standard in supernova cosmology for quite some time,” says Dr Moller.

“This analysis also brings innovative methods that will be used in the next generation of surveys, so we are taking a leap in the way we do science. I’m excited to uncover more about the mystery that is dark energy in the upcoming decade.”

Pioneering a new approach

The new study pioneered a new approach to use photometry — with an unprecedented four filters — to find the supernovae, classify them and measure their light curves. Dr. Möller created the method to select these type Ia supernovae using modern machine learning.

“It is very exciting times to see this innovative technology to harness the power of large astronomical surveys”, she says. “Not only we are able to obtain more type Ia supernovae than before, but we tested these methods thoroughly as we want to do more precision measurements on the fundamental physics of our universe.”

This technique requires data from type Ia supernovae, which occur when an extremely dense dead star, known as a white dwarf, reaches a critical mass and explodes. Since the critical mass is nearly the same for all white dwarfs, all type Ia supernovae have approximately the same actual brightness and any remaining variations can be calibrated out. So, when astrophysicists compare the apparent brightnesses of two type Ia supernovae as seen from Earth, they can determine their relative distances from us.

Astrophysicists trace out the history of cosmic expansion with large samples of supernovae spanning a wide range of distances. For each supernova, they combine its distance with a measurement of its redshift — how quickly it is moving away from Earth due to the expansion of the universe. They can use that history to determine whether the dark energy density has remained constant or changed over time.

The results found w = –0.80 +/- 0.18 using supernovae alone. Combined with complementary data from the European Space Agency’s Planck telescope, w reaches –1 within the error bars. To come to a definitive conclusion, scientists will need more data using a new survey.

DES researchers used advanced machine-learning techniques to aid in supernova classification. Among the data from about two million distant observed galaxies, DES found several thousand supernovae. Scientists ultimately used 1,499 type Ia supernovae with high-quality data, making it the largest, deepest supernova sample from a single telescope ever compiled. In 1998, the Nobel-winning astronomers used just 52 supernovae to determine that the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate.