ESA’s CHaracterising Exoplanet Satellite (Cheops) has provided the crucial pieces of data to understand a mysterious exoplanet system that had been perplexing researchers for years.

The star HD110067 lies around 100 light-years away in the northern constellation of Coma Berenices. In 2020, NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) detected dips in the star’s brightness, indicating planets were passing in front of the star’s surface.

A preliminary analysis revealed two possible planets. One with an orbital period – the time it takes to complete one orbit around the star – of 5.642 days, and the other with a period that could not be determined yet.

Two years later, TESS observed the same star again. Analysing the combined data sets ruled out the original interpretation but presented two possible planets. While these detections were much more certain than the originals, a lot about the TESS data still did not make sense. That was when Rafael Luque of the University of Chicago and his colleagues became interested.

“That’s when we decided to use Cheops. We went fishing for signals among all the potential periods that those planets could have,” says Rafael.

Their efforts paid off. They confirmed a third planet in the system and realised they had found the key to unlocking the whole system because it was now clear that the three planets were in an orbital resonance. The outer-most planet takes 20.519 days to orbit, which is extremely close to 1.5 times the orbital period of the next planet with 13.673 days. This in turn is almost exactly 1.5 times the orbital period of the inner planet, with 9.114 days.

Predicting other orbital resonances and matching them to the remaining unexplained data allowed the team to discover the other three planets in the system. “Cheops gave us this resonant configuration that allowed us to predict all the other periods. Without that detection from Cheops, it would have been impossible,” explains Rafael.

Orbitally resonant systems are extremely important to find because they tell astronomers about the formation and subsequent evolution of the planetary system. Planets around stars tend to form in resonance but can be easily perturbed.

For example, a very massive planet, a close encounter with a passing star, or a giant impact event can all disrupt the careful balance. As a result, many of the multi-planet system known to astronomers are not in resonance but look close enough that they could have been resonant once. However, multi-planet systems preserving their resonance are rare.

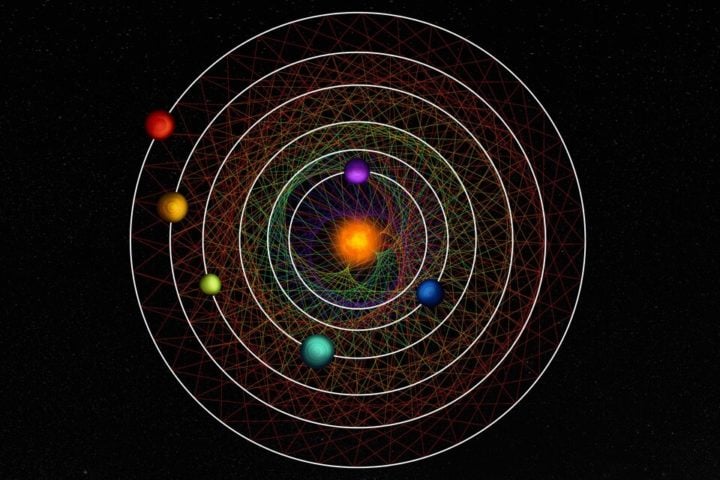

Orbital geometry of HD110067. Image credit: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, Thibaut Roger/NCCR PlanetS

“We think only about one percent of all systems stay in resonance,” says Rafael. That’s why HD110067 is special and invites further study. “It shows us the pristine configuration of a planetary system that has survived untouched.”

“As our science team puts it: Cheops is making outstanding discoveries sound ordinary. Out of only three known six-planet resonant systems, this is now the second one found by Cheops, and in only three years of operations,” says Maximilian Günther, ESA project scientist for Cheops.

HD110067 is the brightest known system with four or more planets. Since those planets are all sub-Neptune-sized with likely extended atmospheres, it makes them ideal candidates for studying the composition of their atmospheres using the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope and the ESA’s future Ariel and Plato telescopes.

Source: European Space Agency