The Webb telescope has opened a new window into the universe, but it builds on missions going back 40 years, including Spitzer and the Infrared Astronomical Satellite.

NASA will celebrate the two-year launch anniversary of the James Webb Space Telescope – the largest and most powerful space observatory in history. The clarity of its images has inspired the world, and scientists are just beginning to explore the scientific bounty it is returning.

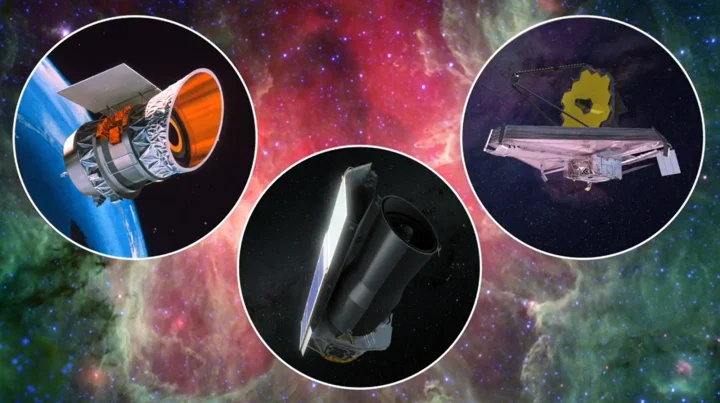

Webb’s success builds on four decades of space telescopes that also detect infrared light (which is invisible to the naked eye) – in particular the work of two retired NASA telescopes with big anniversaries this past year: January marked the 40th year since the launch of the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS), while August marked the 20th launch anniversary of the Spitzer Space Telescope.

This heritage shines through in NASA’s images of Rho Ophiuchi, one of the closest star-forming regions to Earth. IRAS was the first infrared telescope ever launched into Earth orbit, above the atmosphere that blocks most infrared wavelengths. Rho Ophiuchi’s thick clouds of gas and dust block visible light, but IRAS’ infrared vision made it the first observatory to be able to pierce those layers to reveal newborn stars nestled deep inside.

Twenty years later, Spitzer’s multiple infrared detectors helped astronomers assign more specific ages to many of the stars in the region, providing insights about how young stars throughout the universe evolve. Webb’s even more detailed infrared view shows jets bursting from young stars, as well as disks of material around them – the makings of future planetary systems.

Another example is Fomalhaut, a star surrounded by a disk of debris similar to our asteroid belt. Forty years ago, the disk was one of IRAS’ major discoveries because it also strongly suggested the presence of at least one planet, at a time when no planets had yet been found outside the solar system. Subsequent observations by Spitzer showed the disk had two sections – a cold, outer region and a warm, inner region – and revealed more evidence of the presence of planets.

Many other telescopes, including NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, have since studied Fomalhaut, and earlier this year, images from Webb gave scientists their clearest view of the disk structure yet. It revealed two previously unseen rings of rock and gas in the inner disk. Combining the work of generations of telescopes is bringing the story of Fomalhaut into sharp relief.

Visionary Infrared Astronomy Survey

When IRAS launched in 1983, scientists weren’t sure what the mission would reveal. They couldn’t predict that infrared would eventually be used in almost every area of astronomy, including studies of the evolution of galaxies, the life cycle of stars, the source of pervasive cosmic dust, the atmospheres of exoplanets, the movements of asteroids and other near-Earth objects, and even the nature of one of the biggest cosmological mysteries in history, dark energy.

IRAS set the stage for the European-led Infrared Space Observatory (ISO) and the Herschel Space Observatory; the Japanese-led AKARI satellite; NASA’s Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE), and the agency’s airborne SOFIA (Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy), as well as many balloon-lofted observatories.

“Infrared light is essential for understanding where we came from and how we got here, on both the biggest and smallest astrophysical scales,” said Michael Werner, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. Werner, who specializes in infrared observations, served as project scientist for Spitzer.

“We use infrared to look back in space and time, to help us understand how the modern universe came to be. And infrared enables us to study the formation and evolution of stars and planets, which tells us about the history of our own solar system.”

On to Spitzer

If IRAS was a pathfinding mission, Spitzer was designed to dive deep into the infrared universe. Many of Webb’s planetary targets in its first year had already been studied with Spitzer, which pursued a broad range of science goals, thanks to its wide field of view and relatively high resolution.

During its 16-year mission, Spitzer uncovered new wonders from the edge of the universe (including some of the most distant galaxies ever observed at the time) to our own solar system (such as a new ring around Saturn). Researchers were also surprised to find that the telescope was a perfect tool for studying exoplanets (planets beyond our solar system), something they hadn’t expected when building it.

“With any telescope, you’re not just taking data for the sake of it; you’re asking a particular question or a series of questions,” said Sean Carey, a former manager for the Spitzer Science Center at IPAC, a data and science processing center at Caltech. “The questions we’re able to ask with Webb are much more complex and varied because of the knowledge we acquired with telescopes like Spitzer and IRAS.”

For example, Carey said, “We studied exoplanets with Spitzer and Hubble, and we figured out what you can do with an infrared telescope in that field, what types of planets are most interesting, and what you can learn about them. So when Webb launched, we jumped into exoplanet studies right from the get-go.”

Webb, too, is paving the way for future infrared missions. NASA’s upcoming SPHEREx (Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer) mission as well as the agency’s next flagship observatory, the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, will continue to explore the universe in infrared.