An international team of astrophysicists, including Princeton’s Andy Goulding has discovered the most distant supermassive black hole ever found, using two NASA space telescopes: the Chandra X-ray Observatory (Chandra) and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

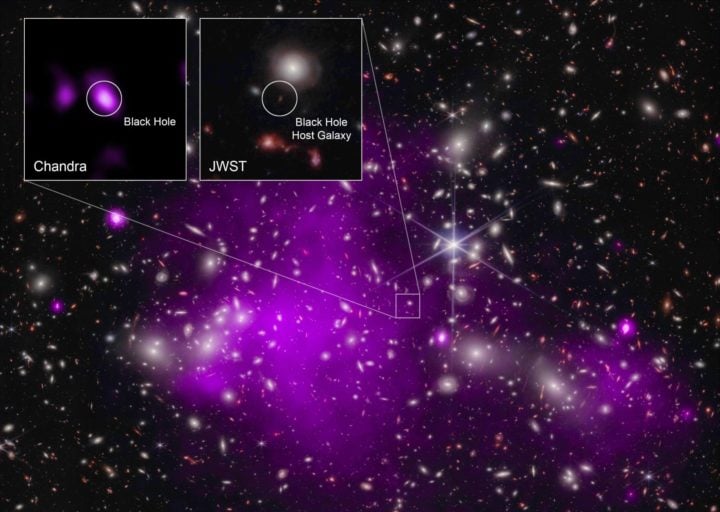

Astrophysicists combined data from JWST and the Chandra X-ray Observatory to identify the growing black hole at the center of this image. Image credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO/Ákos Bogdán et al.; Infrared: NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI; Image processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/L. Frattare, K. Arcand

The black hole, which is an estimated 10 to 100 million times more massive than our sun, is 13.2 billion light-years away in the galaxy UHZ-1, which means the telescopes are peering back in time to when the universe was “extremely young,” Goulding said — only about 450 million years old.

“This is one of the most dramatic discoveries to come out of the James Webb Space Telescope” and the discovery of the most distant growing supermassive black hole known, said Michael Strauss, professor and chair of astrophysical sciences at Princeton, who discussed the findings with the researchers but was not part of the research team. “Indeed, it completely smashes the old record.”

Precisely how the first black holes were formed in the universe’s infancy has been a long-standing debate among astronomers.

“Now, finally discovering a black hole that was so large, when the universe was so young, tells us that the black hole must have been very large when it was initially formed, probably from the direct collapse of a massive gas cloud,” said Goulding, who is a research scientist in Princeton’s Department of Astrophysical Sciences.

It also means that astronomers can rule out other formation models, like the death of the first massive stars, because those couldn’t produce a black hole large enough to explain UHZ-1, he added.

“The black hole has only a very short time to grow,” he said. “It either grew extraordinarily fast or the black hole was simply born larger.”

Goulding is one of the lead authors of the primary paper announcing the result and the lead author of a separate paper in The Astrophysical Journal Letters detailing the mass of the galaxy and its extraordinary distance, which was pivotal to the overall result.

Different telescopes have different tools to peer into the universe, and combining data from multiple instruments can yield more than a sum of their parts. “We needed Webb to find this remarkably distant galaxy and Chandra to find its supermassive black hole,” said Ákos Bogdán of the Center for Astrophysics-Harvard & Smithsonian in the press release. Bogdan is first author on the Nature Astronomy paper.

Written by Liz Fuller-Wright

Source: Princeton University