A McMaster researcher is part of an international team that has found evidence of a potentially habitable icy exoplanet beyond our solar system.

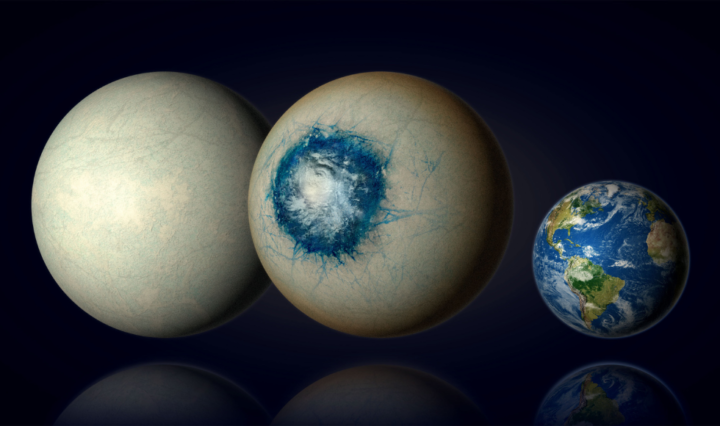

LHS 1140 b may be a world completely covered in ice (left) or an ice world with a liquid substellar ocean and a cloudy atmosphere (centre). It is 1.7 times the size of the Earth and is the most promising habitable zone exoplanet yet in our search for liquid water beyond the solar system. Credit: B. Gougeon/l’Université de Montréal

The exoplanet, named LHS 1140 b, is located about 48 light-years away in the constellation Cetus and orbits a low-mass red dwarf star that is roughly one-fifth the size of the Sun. It is one of the closest exoplanets to our solar system that lies within its star’s habitable zone.

Exoplanets found in this “Goldilocks Zone” have temperatures that could allow water to exist in liquid form, which is a crucial element for life.

“We had enough information about the mass and orbit of LHS 1140 b to successfully make the case to go and check whether it has an atmosphere and may be a prospective place for life elsewhere in the universe,” says Ryan Cloutier, assistant professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, who contributed to the study led by researchers at l’Université de Montréal.

Since its discovery in 2017, one of the critical questions about LHS 1140 b has been whether it is a mini-Neptune type exoplanet – a small gas giant with a thick hydrogen-rich atmosphere, or a rocky planet larger than Earth known as a super Earth. Distinguishing between these two possibilities would require the detailed characterization of the planet’s atmosphere using what Cloutier calls, “the most powerful telescope that humankind has ever built” — the James Webb Space Telescope.

The team was awarded time with Webb last December. Their observations were done with the Canadian-built Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) instrument.

Researchers used these data to rule out the mini-Neptune scenario, with tantalizing evidence suggesting the exoplanet is an icy super-Earth that may even have a nitrogen-rich atmosphere like our own.

“We now have evidence of a secondary atmosphere on a potentially habitable world for the first time,” says Cloutier.

The findings, combined with measurements of the exoplanet’s mass and size, reveal it is less dense than expected for a rocky planet with an Earth-like composition, suggesting that 10 to 20 per cent of its mass may be composed of water. This discovery points to LHS 1140 b being a compelling candidate water world, likely resembling a snowball or ice planet with a potential liquid ocean at the sub-stellar point, which is the area of the planet’s surface that is always facing its star, similarly to the Moon’s locked orbit around the Earth.

“The question of ‘are we alone in the universe’ has been asked for millennia. It’s only in the last three years since the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope that we’ve been able to go and search for signatures of Earth-like planets and confirm whether they’re conducive to hosting life,” explains Cloutier.

“It’s difficult and it requires a lot of time, but it would be so impactful if it was successful. We’re seeing hints of that success here for the very first time. Getting confirmation would be so revolutionary — not just for the field of explanatory astronomy but for scientific exploration.”

More observations with Webb are needed to confirm the presence and composition of LHS 1140 b’s atmosphere and to discern between the snowball planet and bull’s-eye ocean planet scenarios.

The team hopes to focus on a specific signal that could unveil the presence of carbon dioxide, which is crucial for understanding the atmospheric composition and detecting potential greenhouse gases that could indicate habitable conditions on this exoplanet.

Because of limited visibility with Webb, astronomers will have to observe this system at every possible opportunity for several years to determine whether LHS 1140 b has habitable surface conditions.

This planet provides a unique opportunity to study a world that could support life, given its position in the habitable zone and the likelihood of having an atmosphere that can retain heat and support a stable climate.

Source: McMaster University