The Sun’s atmosphere is called the corona. It consists of an electrically charged gas known as plasma with a temperature of around one million degrees Celsius.

Its temperature is an enduring mystery because the Sun’s surface is only around 6000 degrees. The corona should be cooler than the surface because the Sun’s energy comes from the nuclear furnace in its core, and things naturally get cooler the further away they are from a heat source. Yet the corona is more than 150 times hotter than the surface.

Another method for transferring energy into the plasma must be at work, but what?

It has long been suspected that turbulence in the solar atmosphere could result in significant heating of the plasma in the corona. But when it comes to investigating this phenomenon, solar physicists run into a practical problem: it is impossible to gather all the data they need with just one spacecraft.

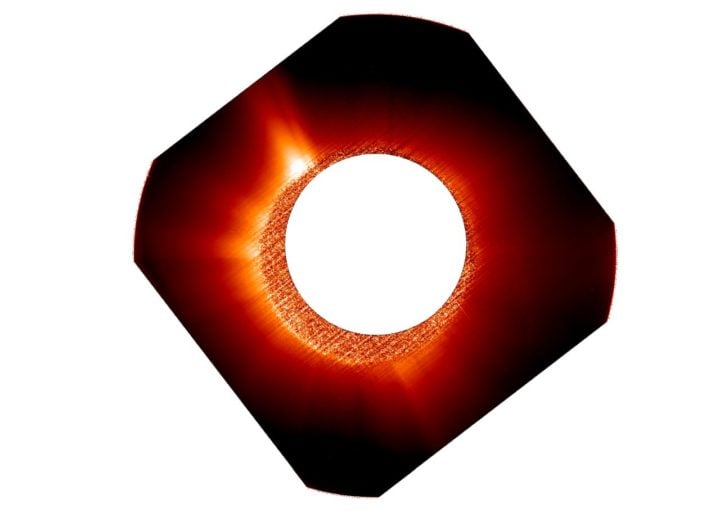

The outer atmosphere of the Sun, known as the corona, can be seen stretching off into space in this image from Solar Orbiter’s Metis instrument. Image credit: ESA & NASA/Solar Orbiter/Metis team; D. Telloni et al (2023)

There are two ways to investigate the Sun: remote sensing and in-situ measurements. In remote sensing, the spacecraft is positioned far away and uses cameras to look at the Sun and its atmosphere in different wavelengths. For in-situ measurements, the spacecraft flies through the region it wants to investigate and takes measurements of the particles and magnetic fields in that part of space.

Both approaches have their advantages. Remote sensing shows the large-scale results but not the details of the processes happening in the plasma. Meanwhile, in-situ measurements give highly specific information about the small-scale processes in the plasma but do not show how this affects the large scale.

To get the full picture, two spacecraft are needed. This is exactly what solar physicists currently have in the form of the ESA-led Solar Orbiter spacecraft, and NASA’s Parker Solar Probe. Solar Orbiter is designed to get as close to the Sun as it can and still perform remote sensing operations, along with in-situ measurements. Parker Solar Probe largely forgoes remote sensing of the Sun itself to get even closer for its in-situ measurements.

But to take full advantage of their complementary approaches, Parker Solar Probe would have to be within the field of view of one of Solar Orbiter’s instruments. That way Solar Orbiter could record the large-scale consequences of what Parker Solar Probe was measuring in situ.

Daniele Telloni, researcher at the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) at the Astrophysical Observatory of Torino, is part of the team behind Solar Orbiter’s Metis instrument. Metis is a coronagraph that blocks out the light from the Sun’s surface and takes pictures of the corona. It is the perfect instrument to use for the large-scale measurements and so Daniele began looking for times when Parker Solar Probe would line up.

He found that on 1 June 2022, the two spacecraft would almost be in the correct orbital configuration. Essentially, Solar Orbiter would be looking at the Sun and Parker Solar Probe would be just off to the side, tantalisingly close but just out of the field of view of the Metis instrument.

As Daniele looked at the problem, he realised all it would take to bring Parker Solar Probe into view was a little bit of gymnastics with Solar Orbiter: a 45 degree roll and then pointing it slightly away from the Sun.

But when every manoeuvre of a space mission is carefully planned in advance, and spacecraft are themselves designed to point only in very specific directions, especially when coping with the fearsome heat of the Sun, it was not clear that the spacecraft operations team would authorise such a deviation. However, once everyone was clear on the potential scientific return, the decision was a clear ‘yes’.

The roll and the offset pointing went ahead; Parker Solar Probe came into the field of view, and together the spacecraft produced the first ever simultaneous measurements of the large scale configuration of the solar corona and the microphysical properties of the plasma.

Artist impression of Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe. Image credit: Solar Orbiter: ESA/ATG medialab; Parker Solar Probe: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL

“This work is the result of contributions from many, many people,” says Daniele, who led the analysis of the data sets. They made the first combined observational and in-situ estimate of the coronal heating rate.

“The ability to use both Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe has really opened up an entirely new dimension in this research,” says Gary Zank, University of Alabama in Huntsville, USA, and a co-author on the resulting paper.

By comparing the newly measured rate to the theoretical predictions made by solar physicists over the years, Daniele has shown that solar physicists were almost certainly right in identifying turbulence as a way of transferring energy.

The specific way turbulence does this is not dissimilar to when you stir your morning cup of coffee. By stimulating random movements of a fluid, either a gas or a liquid, energy is transferred to ever smaller scales, which culminates in energy transformation into heat. In the case of the solar corona, the fluid is also magnetized, so stored magnetic energy is also available to be converted into heat.

Such a transfer of magnetic and movement energy from larger to smaller scales is the very essence of turbulence. At the smallest scales, it allows the fluctuations to finally interact with individual particles, mostly protons, and heat them up.

More work is needed before we can say that the solar heating problem is solved but now, thanks to Daniele’s work, solar physicists have their first measurement of this process.

“This is a scientific first. This work represents a significant step forward in solving the coronal heating problem,” says Daniel Müller, Project Scientist.

Source: European Space Agency