Medical students, health care workers, and even physicians are increasingly using mobile apps in greater numbers to sharpen their medical knowledge. One such medical science learning app challenges users to compete for cash prizes by earning high scores in gamified approaches to motivate their medical skills development.

This developing trend in EdTech adapts existing tools or creates new ones to help people navigate around their learning obstacles. Sometimes, teaching people to learn new skills by entertaining them lets players contribute to the advancement of life science.

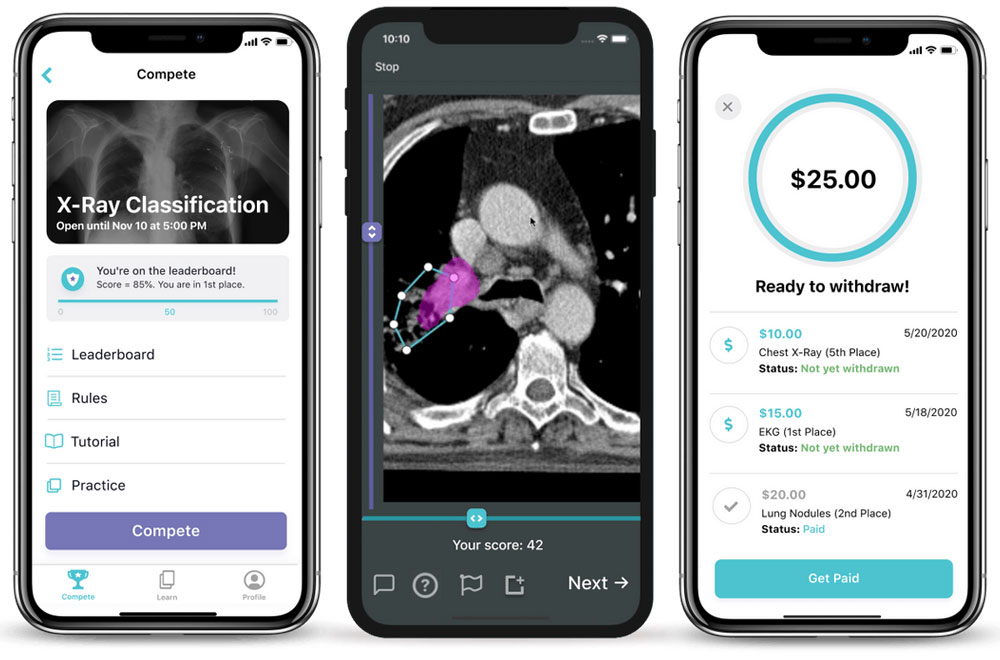

Take the case of a popular app among medical field workers called DiagnosUs. It offers a free yet challenging approach to teaching medical diagnosis skills with real patients’ X-rays and ultrasound images.

Among the app’s primary users are medical students, nurses, lab technicians, and physicians. Users also include health workers wanting to supplement preparation for classes, clerkships, and certification exams for an alphabet soup of medical specialties such as the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE), Clinical Knowledge (CK) Steps 1 and 2, NBME med school readiness test, the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) (MBBS), NCLEX exams and many more.

“All sorts of people comprise our typical users. Currently, it is about half medical students, but there are also many nurses, M.D.s, specialists, and others. Anyone can download the app to play, even if they are not a med student. But obviously, most people have a medical background,” Erik Duhaime, cofounder and CEO of Centaur Labs and creator of the app, told TechNewsWorld.

The app promotes an engaging, dynamic platform to test anyone’s medical knowledge while simultaneously contributing to the development of crucial machine learning algorithms. Often, the app users’ results in labeling medical images are filtered back to Centaur Labs for actual projects involved with other medically oriented projects.

Lab and App Share Common Roots

Duhaime’s background is far from medical. His undergrad and master’s theses were on the evolution of cooperation. He has long been interested in the concept of “When is a group bigger than the sum of its parts.”

That interest led him to start his Ph.D. studies at the MIT Center for Collective Intelligence, where he furthered his interest in how information technology could enable new ways of cooperating.

DiagnosUs Co-Founders (left to right) Tom Gellatly, Erik Duhaime, and Zach Rausnitz

“I also got fascinated by the “wisdom of crowds” phenomenon and the challenge of how to best aggregate multiple opinions from people who have different levels of expertise,” Duhaime offered.

Much of that mind work is evident in how DiagnosUs teaches diagnostic skills. What solidified his interest in applying his crowdsourcing research was his wife’s matriculation through medical school, he noted.

Participatory Medical Learning Works

Growing his concept of learning by doing within the app resulted from Duhaime’s experiments with lay people and what he calls “semi-experts” doing things like classifying skin lesions, he explained.

That is when he found that measuring their performance, discarding the votes of people who seemed to be unskilled at the task, and intelligently combining the opinions of people who were more skilled got productive results.

“I could get groups of these semi-experts to out-perform individual board-certified dermatologists,” he quipped.

Duhaime went a step further and borrowed a technique used in the Duolingo language-learning app. That app aggregated the opinions of unskilled learners to provide translation services for clients like news outlets.

His wife was paying hundreds of dollars for some flashcard apps to study medicine. That was when he realized something similar to Duolingo might work in health care and be able to analyze cases better than individual experts.

Making Use of Proven Design

Duhaime applied those experiences to the design of his app. That gave him a twofold gain. It provided a legitimate learning tool with a focus on science and medicine and a sourcing channel for Centaur Labs services, which he founded in 2017.

Centaur Labs helps AI developers and data scientists label large-scale medical and scientific datasets. As a result, those clients can more quickly and easily build and improve their models.

The lab’s clients belong to a growing niche in the health care industry, which generates nearly 30% of the world’s data volume. The majority of that data is unstructured or poorly annotated.

Familiar Connections

TechNewsWorld earlier this year discussed the use of gamified learning strategies in another EdTech app that helps college students prepare for medical school admissions. That app, King of the Curve, is a disruptive EdTech startup founded by then-college student Heath Rutledge-Jukes.

The DiagnosUs app uses gamified approaches where users can compete for cash prizes, motivating them to develop their medical knowledge.

Now working his way through med school, Rutledge-Jukes is also affiliated with Duhaime’s app. There, he consults on learning techniques and creates valid science-based questions for use in the DiagnosUs app.

“What the founders have done here is make a way to label medical data with users, medical students, and doctors around the world so people can work on the data, help label it, and then sell it back to other companies to build algorithms out of it,” Rutledge-Jukes told TechNewsWorld. The app uses many more practice problems from real cases than a textbook. It is just not even comparable, he observed.

Proving the Theory Works

Rutledge-Jukes recalled one woman in the Philippines who consistently ranked in the two top spots for accurately looking at ultrasounds and determining whether or not the fetus is male or female.

“She was better than doctors and medical students. She just practiced enough and saw hundreds of cases about it. [From that] we recognized that it is still possible to teach people and then also to get paid for it,” he said.

App users learn and improve their skills as they answer questions, also competing for cash prizes, added Duhaime. Not everything on the platform is a “diagnostic” question.

Some questions ask users to classify a particular scientific paper abstract. Other tasks can also appear based on what his Centaur Labs clients want.

Crowdsourcing Results Real

“When we learn to trust someone at a particular task, we then combine that opinion with those of other peoples to drive a very accurate answer on that problem at that task,” said Duhaime.

So, if his users are novices and are learning, that is fine. The staff just does not count their opinions on customer data.

“But if they are really good, we then assign a label, and that is what our clients pay for,” he explained.

The imaging samples can become part of datasets for identifying maladies that Centaur Labs performs for other medical practitioners.

How the App’s Credibility Is Assured

Duhaime aligns questions to elicit either/or responses based on learned visual recognition or data. He calls this process setting gold standards within the app for a particular client’s labeling project. For instance, he could ask for 100 X-rays of the faces of patients with Covid-19 and 100 that don’t.

Three physicians or other clinicians well-trained in a medical area would do the labeling. That ensures that the images used in the questioning process in the app are valid, according to Duhaime.

Leveraging Digital Tech for User Training

Duhaime gave an example of how the app trains users to recognize patterns by referring to a testing sequence based on Eko Health’s digital technology. That company has a digital stethoscope that makes recordings of heart and lung sounds.

“Because it is digital, they can build AI algorithms. To do that for, say, heart murmurs, you need to take your tens of thousands of clips and assign a label for which ones have heart murmurs or not,” he explained.

DiagnosUs first labels a few hundred recordings with multiple certified experts. The app then uses these samples to train its users and identify the top performers. Test construction involves continually mixing those into app questions to do performance measurements.

“As we learn to trust certain labelers, we can determine which case answers do not have a murmur,” he added.

Med Students Have Most To Gain

Medical students are a very motivated bunch. They have a vested interest in using the app, which provides what med schools do not present, noted Duhaime — adding that the traditional curriculum is quite broken.

“Med students spend more time learning organic chemistry than looking at ECGs or chest X-rays, but those are the sorts of skills that you need when you are practicing. So, I think people are really hungry to gain exposure to all sorts of tasks that they don’t get in undergrad or medical school,” he suggested.