On a humid day in February, a small group of workers huddled in front of a large solar panel factory inside Thailand’s biggest manufacturing hub in the eastern coastal province of Chonburi, home to some of the world’s top solar panel-producing companies.

The men and women, mostly in their twenties, all hoped to land a job on a production line assembling solar cells into panels destined for export.

They knew they may not hold the job for very long after reading complaints of former employees on social media about work being regularly cut when orders were low.

But the company promised fair pay and, needing work, they were willing to take the risk.

That risk is growing, as Thailand’s solar industry has become caught in an escalating trade war between the US and China, with Thai solar workers paying the price.

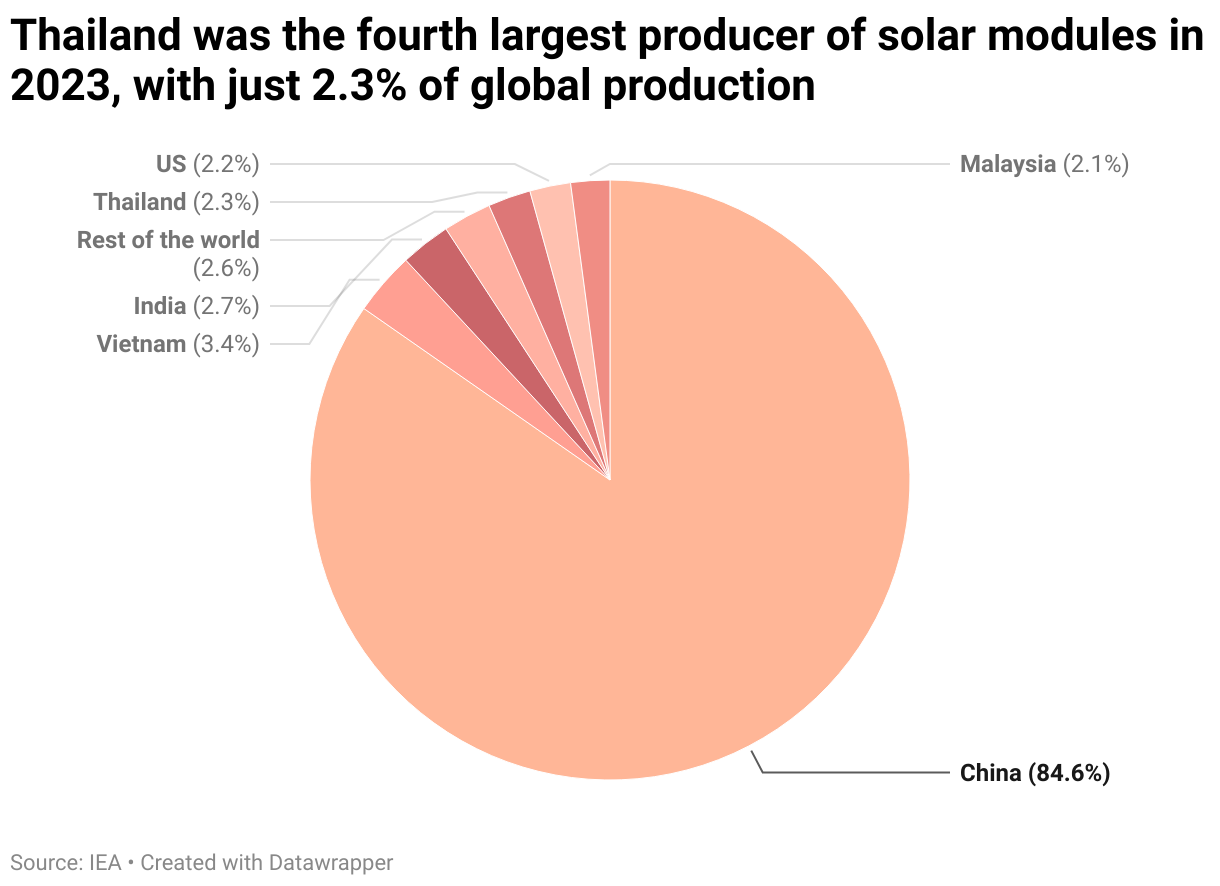

Large Chinese companies dominate Thailand’s solar manufacturing industry, which produces solar cells and panels for export to the US market.

But as Washington erects trade barriers to protect its homegrown solar sector from a rising tide of cheap Chinese imports, Thailand’s industry is being squeezed.

Solar manufacturers in Southeast Asia’s second-largest economy that rely heavily on Chinese components are now facing nearly 400% tariffs to export their products to the US.

Analysts say the tariffs threaten to hurt Thailand’s manufacturing sector and its workers, and could have a knock-on impact on solar rollout in the country. But the changing trade landscape also creates an opportunity for producers to find new markets, including by accelerating solar deployment and the energy transition across the Southeast Asian region.

The heat of the solar trade war

For more than a decade, the US has waged a tariff war on growing imports of cheap Chinese solar panels, which it says harm its domestic industry.

China’s mass production of solar cells and modules has enabled the expansion of clean energy globally. The cost of solar panels has declined by 90% in the past decade. But China’s subsidised and cut-price solar production has also led to accusations of unfair trade practices.

In response, Chinese manufacturers relocated the final production stages to neighbouring Asian countries in an attempt to avoid the US import tax, turning Southeast Asia into a major solar-panel assembly hub and export base.

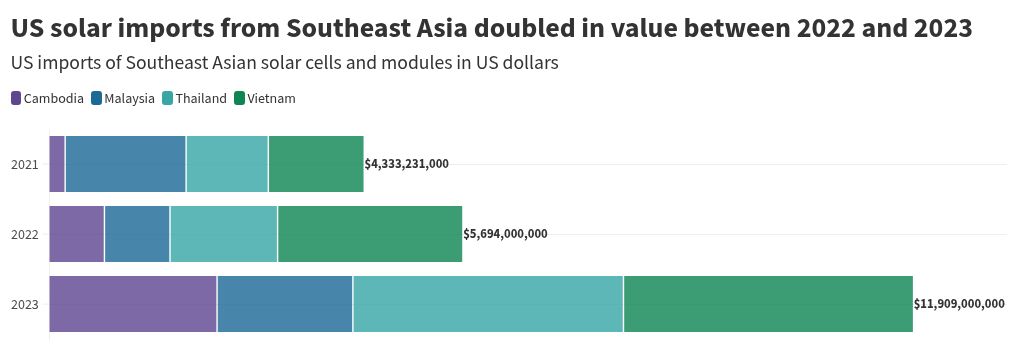

As Chinese exports of solar components to Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia and Cambodia boomed, so did US imports of Southeast Asian solar panels.

By 2023, 80% of US solar module imports came from those four countries. Nearly a quarter came from Thailand alone.

But in recent months, several Chinese manufacturers with factories in Southeast Asia suspended some of their operations in the region, after the US announced a string of antidumping duties on solar imports from the four countries in a bid to close the loophole.

Thousands working in Thailand’s solar factories – most of whom had left the agricultural north of the county to seek better-paid employment in an industry which promised decent jobs – were put on leave or suddenly dismissed.

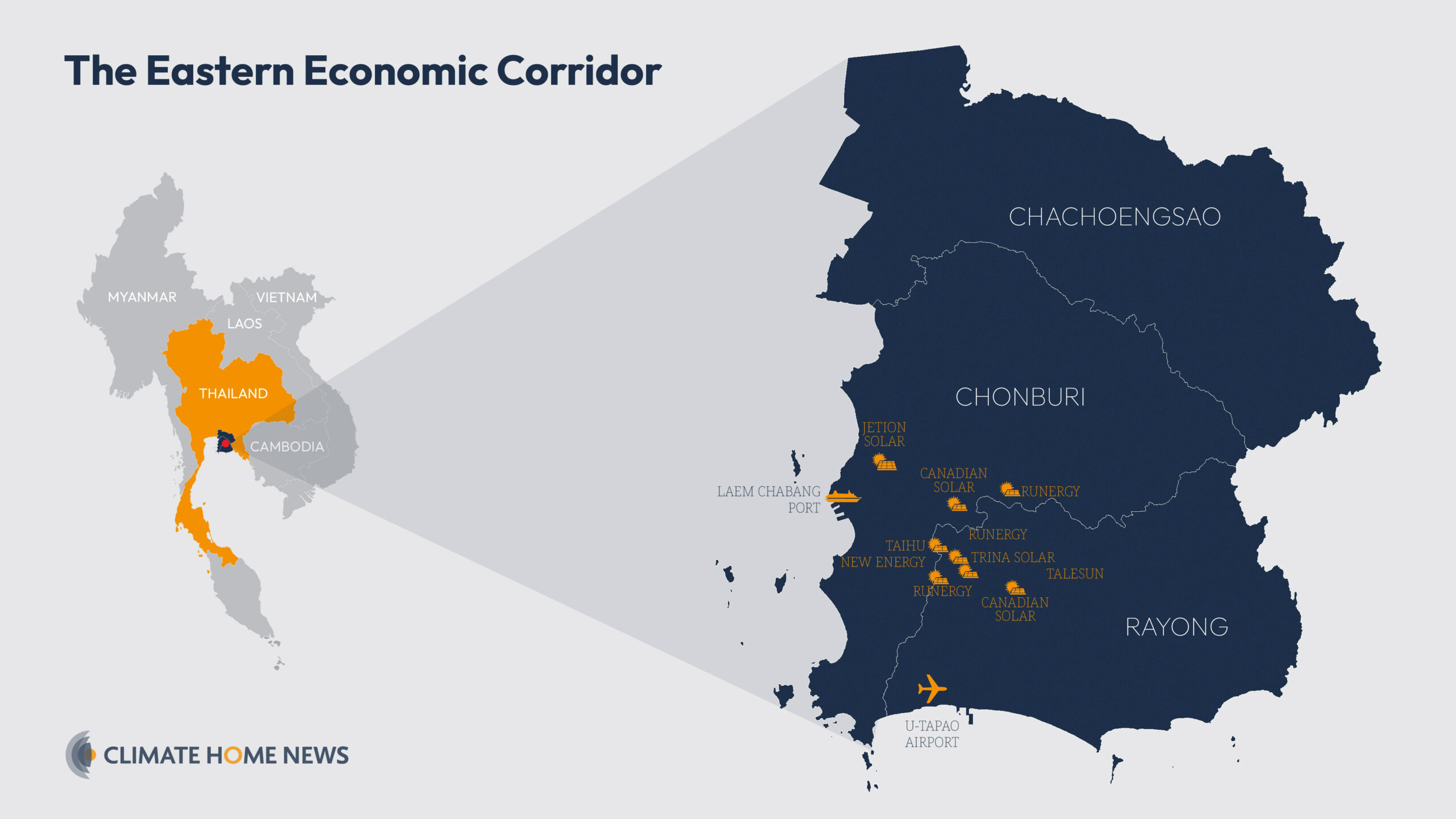

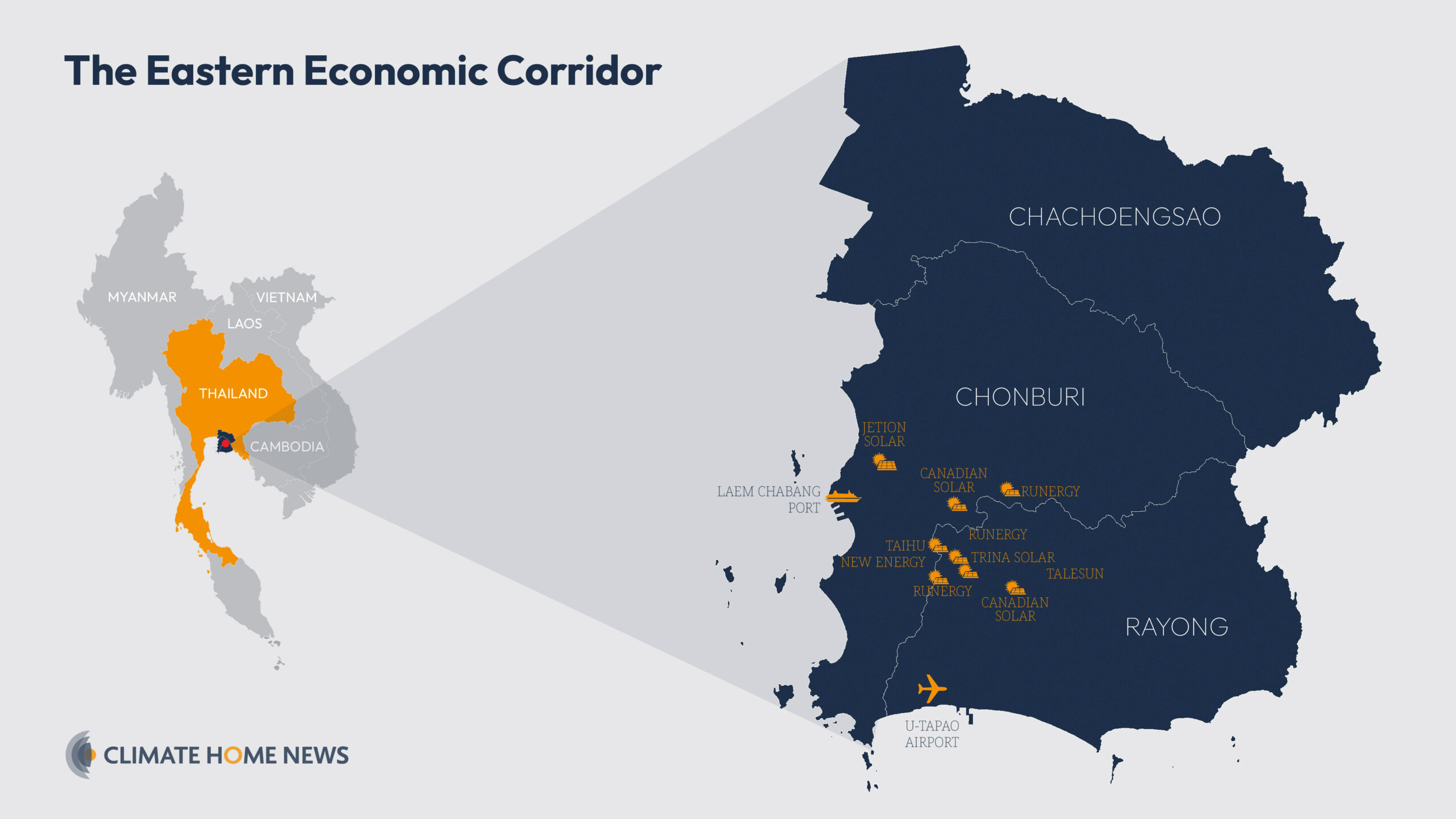

Climate Home News analysed local media reports and social media posts relating to worker dismissals at three leading solar manufacturers with factories in the Eastern Economic Corridor, the country’s largest manufacturing zone: Chinese companies Runergy and Trina Solar, one of the world’s largest solar PV manufacturing firms, and Canadian Solar, which has long conducted most of its manufacturing operations in China.

We found that close to 8,000 full-time staff and subcontracted workers were either temporarily or permanently dismissed in 2024. Over that time, US officials investigated a complaint from American manufacturers that companies with factories in Southeast Asia were dumping subsidised and unfairly cheap products on the US market.

An industry losing its grip on its biggest export market

Last month, US trade officials unveiled hefty tariffs of at least 375% on imports of solar cells from Thailand.

The US International Trade Commission, a bi-partisan government agency, is due to make a final decision about the tariffs in June. In private, analysts say they are likely to be approved.

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) recently found that any price increases beyond 250% would make most Southeast Asian imports “untenable”.

“Any company in any country where the combined tariffs is greater than 250% will likely see their orders decline or get cancelled,” Grant Hauber, of IEEFA, told Climate Home.

Over the past year, US officials’ tariff deliberations rocked Thailand’s solar industry.

“There has been a broad suspension of operations among Chinese companies in Southeast Asia, including Thailand, with many closures likely to be permanent,” said Linxiao Zhu, a research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

“The region risks losing a significant share of its solar manufacturing capacity due to the loss of access to the US market.”

“Thailand’s solar manufacturing industry faces some serious challenges,” agreed Forbes Chanthorn, BloombergNEF’s Thailand energy transition analyst based in Singapore. “It is losing its grip on some of its biggest export markets without any short-term alternatives in sight.”

And the situation could go from bad to worse as US President Donald Trump threatens an additional 37% import tariff on all goods from Thailand – one of the highest rates in Washington’s planned universal tariff onslaught, now paused until June. If applied, this would push the tariffs on Thailand’s solar cells up to 426%.

In an interview, Charuwan Phipatana-Phuttapanta, a solar expert at Thailand’s energy ministry, acknowledged that the tariffs will impact employment in the country’s solar industry.

Workers fall victim to tariffs

Spanning three provinces on Thailand’s eastern coast, the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) is key to the government’s plan to transform the area into an economic powerhouse.

Enticed by generous tax breaks and cheap labour, international companies have flocked here to manufacture everything from air conditioners to batteries for electric vehicles and solar panels for the regional and global markets.

Several leading Chinese solar manufacturing companies set up shop in the EEC nearly a decade ago. Soon, Thailand’s solar exports to the US soared.

But in June 2024, a two-year US tariff waiver on solar products from Southeast Asia – introduced by Joe Biden to boost solar deployment in the country – came to an end. Companies in the region importing silicon wafers from China to make solar cells for export to the US became subject to tariffs.

In the days that followed, several manufacturers slowed down or suspended operations, letting go of staff to adjust to the new tax regime, Amnuay Ngamnet, director of Rayong Labour Protection and Welfare office, the labour ministry’s local representative, told Climate Home.

In Rayong alone, the most southern of the EEC’s three provinces, 3,200 full-time workers at five solar factories were put on leave between 2022-2024, according to official data.

Videos posted on TikTok in recent weeks show deserted parking lots and unusually quiet grounds around some solar factories.

“No matter how good you are, if life stumbles, you cannot succeed. Goodbye,” one solar worker posted on the social media platform with a photo of a dismissal letter.

Amnat (whose name has been changed because of concerns that speaking to the media might affect his job prospects) was among thousands affected.

Like many others, the 39-year-old left his hometown in the agricultural northeastern region in 2022 to find a better-paid job at a solar plant in the EEC.

“It seemed like a promising industry. I hoped to spend years there,” Amnat told Climate Home over the phone. “But it didn’t turn out that way.”

Amnat worked as a subcontractor at a few Chinese solar factories, eventually landing a staff position at Runergy, which manufactures solar cells and modules.

He worked six days a week and earned approximately 25,000 baht ($745) a month, way above the average income for unskilled workers.

But in October 2024, he was dismissed along with “almost all of the employees” at the factory, according to local media reports. Amnat told Climate Home the retrenchment affected nearly 3,000 workers.

Runergy did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

The same month, Runergy opened its first module manufacturing plant in the US to keep supplying the American market – one of a number of solar companies hoping to benefit from tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

As a permanent employee, Amnat was compensated 75% of his monthly wage, a lifeline during the three months it took him to find another job. But others were not so lucky.

Thousands of workers hired as subcontractors and benefiting from fewer rights were left without work or pay overnight as companies suspended some of their operations.

At risk of labour rights violations

“After leaving the solar company, my girlfriend was left unemployed for two months. It was difficult for us,” a TikTok user who had complained about the dismissals on social media, told Climate Home. The subcontracting company employing her made her sign a dismissal letter, absolving it of paying the compensation she was entitled to, he explained.

Bunyuen Sukmai, a local labour lawyer and rights activist, told Climate Home “most workers are not aware that the practice violates their rights” despite being routinely deployed.

In the workers’ housing estate, a few kilometres outside the industrial zone, the offices of subcontracting firms are flanked by hair salons and restaurants. A steady stream of job-seekers fill in application forms and scan QR codes to follow job announcements on social media.

“Subcontractors are usually the first to be affected by industry changes. They usually receive lower benefits and are most at risk of having their rights violated,” said Sukmai. But legal cases over unfair dismissal are rare as few workers have the resources to go down the judicial route, he added.

A representative of Trina Solar in Thailand declined to respond to questions. Canadian Solar did not respond to Climate Home’s repeated requests for comment.

However, in a letter dated June 2024 and shared on social media, Canadian Solar said it had paused operations at one of its factories to make changes to its production line and improve machinery. “Due to the current economic conditions and trade competition, the company needs to adjust to the market situation and the direction of the domestic and international economy,” it said.

It added that it had “great confidence in the potential and economic conditions of Thailand” where it intended to continue operating.

In search of new markets

Some large Chinese panel-makers have already started setting up production lines in Indonesia and Laos, which are not currently affected by the US solar import duties.

The Middle East has also emerged as a growing destination for Chinese solar investments, including for the production of key solar components such as polysilicon ingots and wafers.

“These efforts are designed to forge a supply chain completely outside of China serving the Middle East, the US, and other markets that may be subject to tariff risks,” Zhu wrote in a recent report for The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

To continue operating in Thailand, analysts say large solar manufacturers will need to seek new export markets outside of the US.

In the short-term, exports could be redirected to the European Union and India. The Thai government is racing to finalise a free-trade deal with the EU, where demand growth for solar equipment may be stronger than in the US, Laura Schwartz, a senior Asia analyst at risk intelligence company Verisk Maplecroft, told Climate Home.

“However, over half of China’s solar cell and module exports already go to Europe, so Thai exports would face stiff competition,” said Schwartz. And Indian solar developers will have to use locally made solar cells in government projects from June 2026.

But the tariffs could also mark “a turning point” for Southeast Asia’s solar industry, which could focus on supplying emerging markets in Africa and South America, and urgently accelerate the region’s own solar deployment, said Christina Ng, director of the Energy Shift Institute, a think-tank focused on Asia’s energy transition.

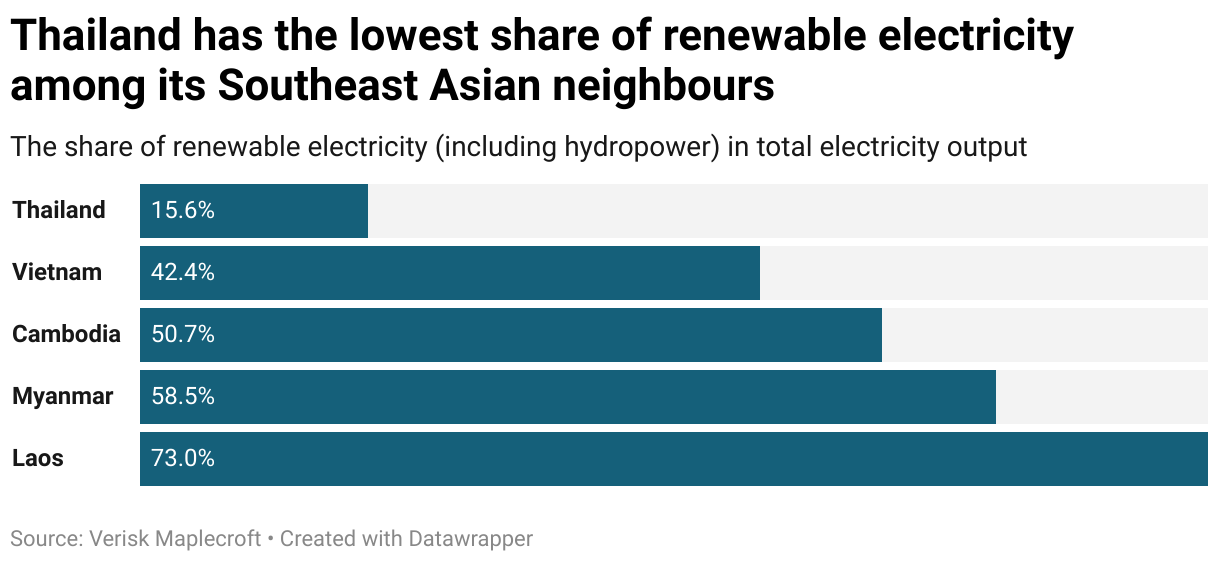

Thailand is dependent on gas for electricity generation but the government has set out plans for 51% of its electricity to come from renewables by 2037, with most of the additional renewable power expected from solar. Only around 3% of Thailand’s electricity currently comes from solar.

Thai companies assembling solar modules in the country are already calling for more incentives to expand a homegrown supply chain.

Krit Pornpilailuck, CEO of Solar PPM, fears Chinese solar manufacturers that can’t export their goods to the US “will flood the Southeast Asian market and plunge the price” of modules.

To protect the industry, Pornpilailak wants to see more support for Thai manufacturers to produce solar cells and other upstream components domestically.

“Thailand has more than six million tonnes of solar-grade quartz reserves that could be used to produce polysilicon – the key ingredient to produce solar wafers,” said Phipatana-Phuttapanta, the government’s solar expert. Although developing the resources would require “technical expertise and high investment”, she added.

“This is a chance for [manufacturers] to move up the value chain – from being seen as mainly low-cost assemblers to becoming leaders in more advanced clean energy technologies,” said Ng. “If the region takes this moment seriously and diversifies, it won’t just weather the disruption; it will emerge more resilient and competitive.”