As different nations begin conducting operations on the lunar surface, humanity’s penchant for geopolitical struggles will likely be along for the ride. Tension between nations and/or corporations could grow. There are few rules and treaties that can calm this potential rising tension. What kinds of conflict might erupt and how can it be prevented?

Humans have shown an ineptness when it comes to dividing things fairly. In multiple cases, nations attempt to take by force what could be shared peacefully. The same is true with companies in competition with one another. Researchers have developed a table-top exercise to examine how competition on the moon could play out.

The article “The potential for conflict in cislunar space: Findings from a tabletop exercise” was published in the journal Space Policy. The lead author is Mariel Borowitz from the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

“To examine the possibility of conflict resulting from activities on the moon, we designed a tabletop exercise (TTX) set in 2029, just five years in the future from the perspective of participants,” the authors write. “In the exercise, countries and private entities find themselves in a hypothetical scenario involving conflicting interests in regard to a commercial ‘safety zone’ claim.”

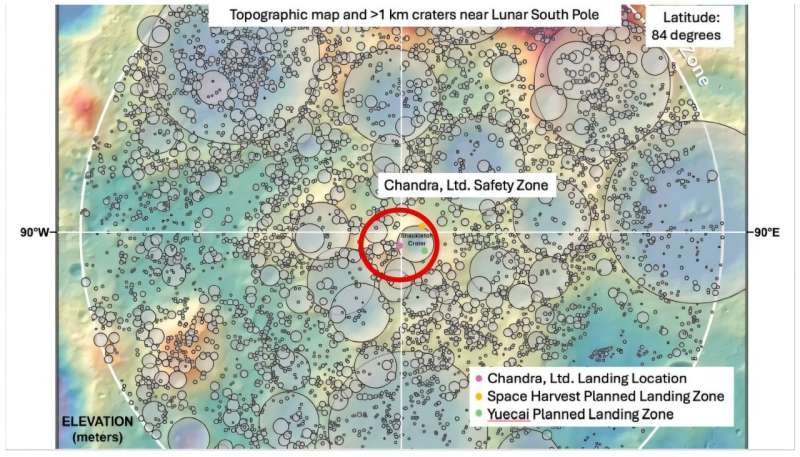

The tabletop game centered on conflicting definitions of the safety zone among fictional competitors. One of the fictional competitors is called “Chandra Ltd.” and is based in India. Chandra lands a spacecraft near the Shackleton Crater on the lunar south pole. It’s a prominent crater about 21 km in diameter. It’s significant because parts of it are in permanent shadows and desirable water ice deposits persist there, while its rim receives a lot of sunlight, desirable for solar power.

After landing near Shackleton Crater, Chandra declares a safety zone with a 50 km diameter that encompasses the entire crater.

Next, two other fictional commercial entities enter the picture, one Chinese and one American. They’re named Yuecai and Space Harvest respectively. Both had previously announced their intended landing sites, but now both lie within Chandra’s declared safety zone.

This is where the TTX begins.

“The use of TTX is relevant for both political science and policy,” the authors write. “Tabletop exercises, wargames, scenario analysis, and simulations are part of a burgeoning trend in international relations scholarship. In particular, TTXs, a type of wargame, were developed for military strategists and simulate real-world environments using hypothetical scenarios .”

The TTX proceeded in two phases. The first involves teams discussing the scenario and reacting to it in small teams. In the second phase, the teams refined their positions and took part in a discussion moderated within the framework of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS). COPUOS was established in 1959 to promote international cooperation on the peaceful uses of space.

A total of 24 participants took part in the TTX, eight teams of three people each. All of the participants are experts in “space and regional dynamics,” according to the authors. The teams represent the United States (military), United States (civil/commercial), Europe, India, UAE, Russia, China, and United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UN COPUOS) Bureau. Members of the research team sat in as observers and took notes throughout the entire TTX. (In reality, the U.S. would almost certainly have one consolidated position, but they were split into two in order to identify unique perspectives in the TTX.)

In the first phase, participants reacted to the scenario and determined whether or not their nation or organization would accept Chandra’s safety zone and their reasons for either accepting it or not. Then they convened in two multilateral blocks for discussions. One was based on the Artemis Accords and included the United States, Europe, India, and the UAE. The second block was the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) group, with Russia and China.

The U.S. Military team saw India’s safety zone as an attempt to prevent Chinese interference. They referenced “aggressive behavior in the South China Sea against the claims of other regional states,” and called on the international community to follow existing law. The team proposed this statement: “The U.S. military asks that all nations consider the principles delineated within the Artemis Accords regarding the importance of operations taking place on the lunar surface, and refrain from any intentional actions that may create harmful interference with each other’s use of outer space in their activities under these Accords.”

The United States’ civil/commercial group spent a lot of time considering how the safety zone would impact future commercial activities. They were concerned that the safety zone could lead to a default claim of ownership by Chandra Ltd. and urged for a more formal process to create safety zones and what exactly they mean. They also considered whether a safety zone requires ongoing activity rather than just the presence of some type of facility.

The European countries agreed with much of what the U.S. civil/commercial group said. They mirrored the idea that while safety zones have a purpose, they shouldn’t be exclusionary. They stressed communication and transparency between all groups and that the safety zones should be in place to prevent disruption of scientific activities. (It should be noted that there’s a long history of nations claiming their actions are scientific when they’re not. See Japanese Whaling.)

The Indian team was understandably focused on justifying Chandra’s actions. They considered Chandra to be aligned with Indian space policy, which supports commercial space development. They thought that Chandra’s safe zone was also aligned with the Artemis Accords and implementing it was consistent with the accords. They said the safety zone was for notification purposes and that they still upheld the principle of free lunar access and that the zone’s size is “based on a technical analysis of potential mission interference concerns.”

The UAE team concluded that their biggest contribution would be to host conversations relying on their relationships with the other groups. They proposed an international conference on space governance to work through conflicts.

In the TTX scenario, China had plans to land in the same region as the safety zone. The Chinese team refused to accept Chandra’s safety zone and deemed it illegitimate and unenforceable. They said the safety zone has no basis in law and that the Chinese company would not recognize the zone nor change their landing plans.

They were also wary about normalizing private actors’ ability to declare things like safety zones and make other claims, so as not to dilute the authority of nations. China also called for a more inclusive approach, and “viewed the United Nations as the only legitimate avenue for resolving lunar disputes, seeking a more ‘global process.'” Perhaps cynically, they called for a more transparent approach.

Russia flatly denied that Chandra Ltd. had the authority to declare a safety zone. They saw it as an infringement on other nations’ sovereign rights. They took a shot at the Artemis Accords as being simply a U.S.-led effort that lacked inclusivity.

“Although not explicitly stated, there appeared to be underlying concerns that Russia might struggle to compete effectively with U.S. and other private companies, given the burden of the Ukraine war and the technical and funding problems facing its space program,” the authors write. They warned that the moon could turn into a sort of capitalist “Wild West” scenario if the U.S. set the rules.

The United Nations team spent considerable time defining what exactly their role should be. They focused on how they could help nations navigate the issue and discussed how COPUOS could work to clarify the definition of a safety zone and get the actors to reach consensus on whether they’re temporary or permanent, whether it could be moved or shifted, and related questions.

“What the team struggled with more than anything was in defining COPUOS’ role in a situation similar to one laid out in the exercise—could it serve as an adjudicator, could it only help define terms, or is it merely a forum for discussion in the event that the nation-state’s involved decide they need a third-party,” the authors write.

In the second phase, the teams convened in the two multilateral blocks, Artemis and the International Lunar Research Station, for discussions moderated by the UN team. The discussions are too in depth to cover completely, but there were some themes.

Narratives around lunar exploration are still evolving, and participants emphasized that for nations that support commercial endeavors on the moon, there needs to be some guardrails. “One participant suggested that the current US position of allowing almost anything for a price could undercut its reputation as a leader in space safety and sustainability,” the authors write.

There were notable calls for more discussion and an effort to clarify and build governance. “This approach could facilitate dialogue and generate new ideas,” the researchers write. “The establishment of the UNCOPUOS Action Team for Lunar Activities Coordination (ATLAC), which occurred in reality shortly after this TTX took place, aligns well with this idea.”

The TTX showed that participants didn’t enter the exercise with clear rules they wanted to establish. None emerged from the scenario. “Instead, the focus was more on the process of developing rules—ensuring that it was fair, inclusive, and adaptable—than on the specific content of the rules,” the authors write. While there’s a desire to establish norms and rules, the participants don’t seem to know what they should be.

In their conclusion, the authors explain that “Participants gained an appreciation of how a simple declaration by a state trying to deconflict the activities of one of its commercial companies with the plans of other states and their companies could lead to an international crisis, due to the current lack of an internationally accepted procedure.” Interestingly, it wasn’t the safety zone itself that caused the most concern, instead it was the lack of a transparent multilateral process for declaring one. Some nations also disliked the idea that non-state actors could declare safety zones.

“In the end, preventing conflict related to activities on the moon will depend on the perceived legitimacy of these procedures,” the authors write in their conclusion. We’re fortunate that there’s still time to work through these issues before lunar exploration and development really gets going.

“But the clock is ticking, and it would be far better to have a governance regime in place before future conflicts occur than to try to develop one after the fact,” the researchers conclude.

More information:

Mariel Borowitz et al, The potential for conflict in cislunar space: Findings from a tabletop exercise, Space Policy (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.spacepol.2025.101700

Citation:

Tabletop exercises can help us understand and avoid potential conflicts over the moon (2025, June 20)

retrieved 22 June 2025

from https://phys.org/news/2025-06-tabletop-potential-conflicts-moon.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.