The demise of a West Antarctic glacier poses the world’s biggest threat to raise sea levels before 2100 — and an ice shelf that’s holding it back from the sea could collapse within three to five years, scientists reported December 13 at the American Geophysical Union’s fall meeting in New Orleans.

Thwaites Glacier is “one of the largest, highest glaciers in Antarctica — it’s huge,” Ted Scambos, a glaciologist at the Boulder, Colo.–based Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, told reporters. Spanning 120 kilometers across, the glacier is roughly the size of Florida, and were the whole thing to fall into the ocean, it would raise sea levels by 65 centimeters, or more than two feet. Right now, its melting is responsible for about 4 percent of global sea level rise.

But a large portion of the glacier is about to lose its tenuous grip on the seafloor, and that will dramatically speed up its seaward slide, the researchers said. Since about 2004, the eastern third of Thwaites has been braced by a floating ice shelf, an extension of the glacier that juts out into the sea. Right now, the underbelly of that ice shelf is lodged against an underwater mountain located about 50 kilometers offshore. That pinning point is essentially helping to hold the whole mass of ice in place.

But data collected by researchers beneath and around the shelf in the last two years suggests that brace won’t hold much longer. Warm ocean waters are inexorably eating away at the ice from below (SN: 4/9/21; SN: 9/9/20). As the glacier’s ice shelf loses mass, it’s retreating inland, and will eventually retreat completely behind the underwater mountain pinning it in place. Meanwhile, fractures and crevasses, widened by these waters, are swiftly snaking through the ice like cracks in a car’s windshield, shattering and weakening it.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

This deadly punch-jab-uppercut combination of melting from below, ice shattering and losing its grip on the pinning point is pushing the ice shelf to imminent collapse, within as little as three to five years, said Erin Pettit, a glaciologist at Oregon State University in Corvallis. And “the collapse of this ice shelf will result in a direct increase in sea level rise, pretty rapidly,” Pettit added. “It’s a little bit unsettling.”

Satellite data show that over the last 30 years, the flow of Thwaites Glacier across land and toward the sea has nearly doubled in pace. The collapse of this “Doomsday Glacier” alone would alter sea levels significantly, but its fall would also destabilize other West Antarctic glaciers, dragging more ice into the ocean and raising sea levels even more.

That makes Thwaites “the most important place to study for near-term sea level rise,” Scambos said. So in 2018, researchers from the United States and the United Kingdom embarked on a joint five-year project to intensively study the glacier and try to anticipate its imminent future by planting instruments atop, within, below it as well as offshore of it.

This pull-out-all-the-stops approach to studying Thwaites is leading to other rapid discoveries, including the first observations of ocean and melting conditions right at a glacier’s grounding zone, where the land-based glacier begins to jut out into a floating ice shelf. Scientists have also spotted how the rise and fall of ocean tides can speed up melting, by pumping warm waters farther beneath the ice and creating new melt channels and crevasses in the underside of the ice.

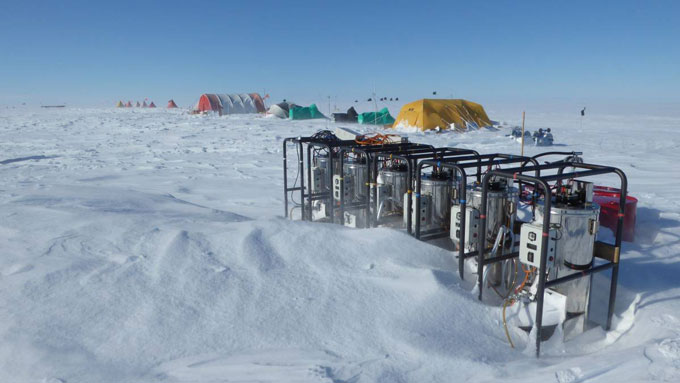

To better understand the rapid retreat of Thwaites Glacier, scientists drilled a hole through the ice at the glacier’s grounding zone, the region where the land-based glacier juts out into the sea to become a floating ice shelf. Heated water (heaters shown here) carved a borehole through the ice down to the grounding zone, allowing scientists to take the first ever measurements of ocean conditions in the region.PETER DAVIS/BAS

To better understand the rapid retreat of Thwaites Glacier, scientists drilled a hole through the ice at the glacier’s grounding zone, the region where the land-based glacier juts out into the sea to become a floating ice shelf. Heated water (heaters shown here) carved a borehole through the ice down to the grounding zone, allowing scientists to take the first ever measurements of ocean conditions in the region.PETER DAVIS/BAS

As Thwaites and other glaciers retreat inland, some scientists have pondered whether they might form very tall cliffs of ice along the edge of the ocean — and the potential tumble of such massive blocks of ice into the sea could lead to devastatingly rapid sea level rise, a hypothesis known as marine ice cliff instability (SN: 2/6/19). How likely researchers say such a collapse is depends on our understanding of the physics and dynamics of ice behavior, something about which scientists have historically known very little (SN: 9/23/20).

The Thwaites collaboration is also tackling this problem. In simulations of the further retreat of Thwaites, glaciologist Anna Crawford of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland and her colleagues found that if the shape of the land beneath the glacier dips deep enough in some places, that could lead to some very tall ice cliffs — but, they found, the ice itself might also deform and thin enough to make tall ice cliff formation difficult.

The collaboration is only at its halfway point now, but these data already promise to help scientists better estimate the near-term future of Thwaites, including how quickly and dramatically it might fall, Scambos said. “We’re watching a world that’s doing things we haven’t really seen before, because we’re pushing on the climate extremely rapidly with carbon dioxide emissions,” he added. “It’s daunting.”