Forest destruction surged to record highs in 2024 as the effects of climate change supercharged human-made fires in some of the planet’s most critical carbon stores, an annual survey by the World Resources Institute (WRI) found.

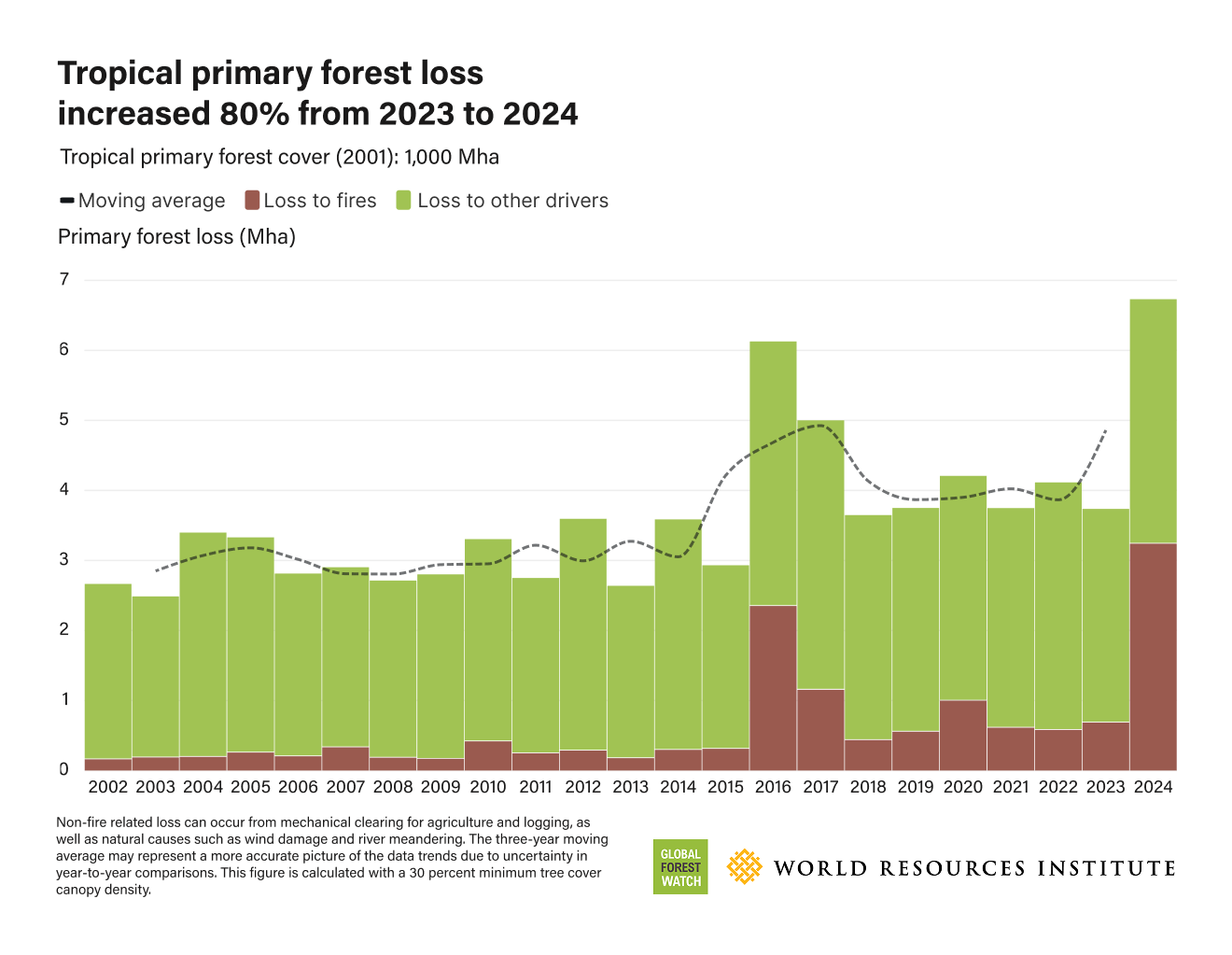

The world lost 6.7 million hectares of primary tropical forest last year – nearly twice as much as in 2023 – at a rate of 18 football fields vanishing every minute, said the report based on new data from the University of Maryland.

Elizabeth Goldman, co-director of the Global Forest Watch observatory, said this unprecedented level of forest loss sends “a global red alert”.

“Every country, every bank, every international business continuing down this path will devastate economies, people’s jobs, and any chance of staving off climate change’s worst effects,” she added.

Primary tropical forests – such as the Amazon in Latin America, the Congo Basin and rainforests in Southeast Asia – are critical carbon sinks that help regulate the global climate by absorbing vast amounts of planet-heating CO2.

In 2024, fires were the main cause of forest loss in tropical forests for the first time since WRI’s survey began two decades ago.

Climate-change feedback loop

In areas like the Amazon or the Congo Basin, fires do not occur naturally but are almost entirely caused by humans, usually as a quick way to clear land for agriculture, experts told reporters in a briefing.

But, while those humid ecosystems have historically been able to stop fires from spreading, hotter and drier conditions caused by climate change and the recurring El Niño weather pattern have now made them more flammable.

Comment: Why governments should not hide behind forests to meet their emissions goals

Rod Taylor, director of forests and nature conservation at WRI, said the world has entered a “new phase”.

“It is not just clearing for agriculture that is the main driver [of forest loss],” he explained. “Now we have this new amplifying effect – a real climate-change feedback loop with fires much more intense and much more ferocious than they have ever been.”

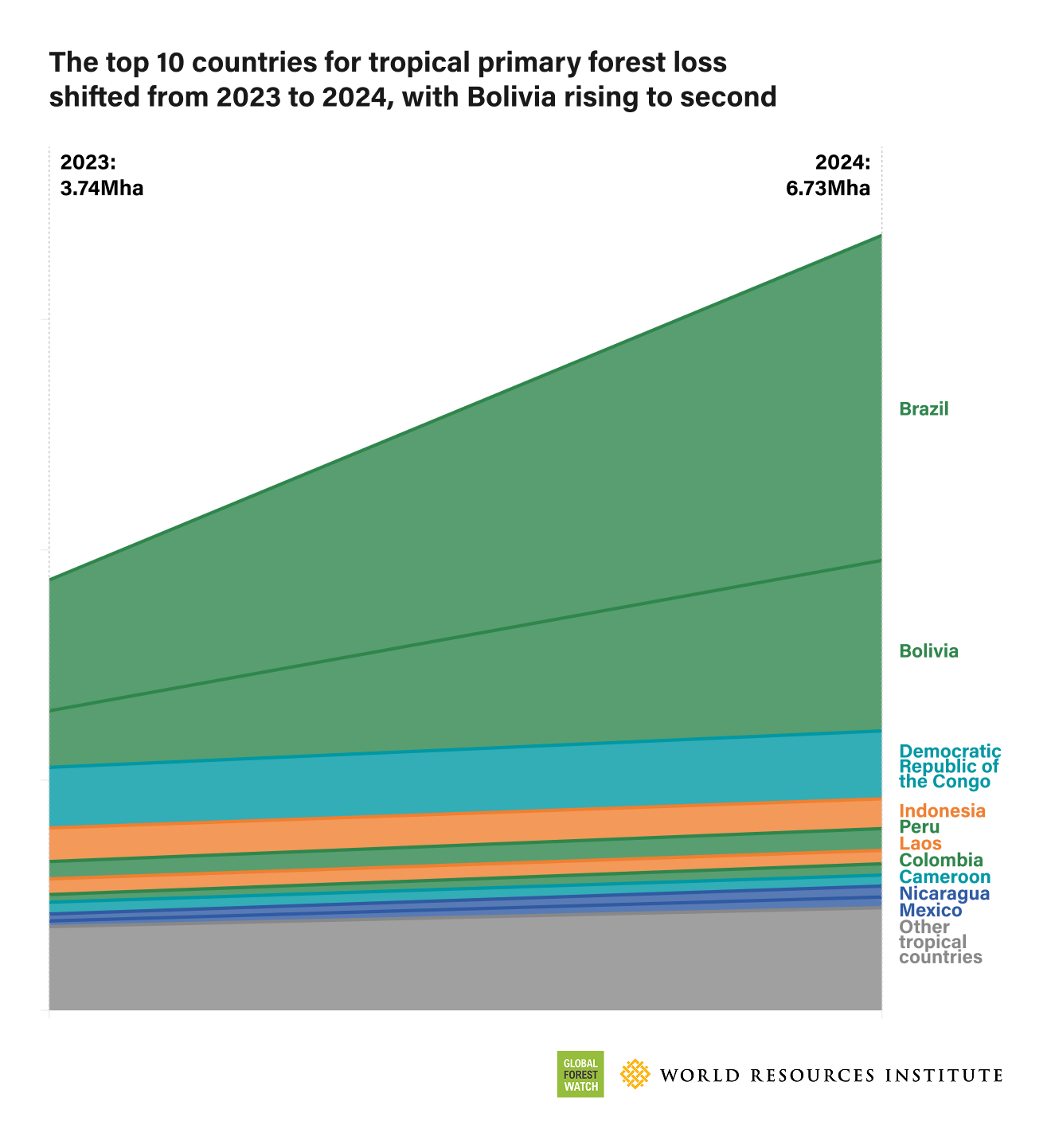

Latin American countries – home to the Amazon rainforest – led forest destruction in 2024 under the combined effect of surging fires made worse by extreme drought conditions and land clearing for large-scale agriculture and cattle-farming.

Agribusiness pressure in Brazil and Bolivia

Brazil alone accounted for 42% of all tropical forest loss last year, the data showed, more than reversing a decline seen in 2023 when it reached a low level under the new left-wing government of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

After promising to achieve net zero deforestation in the Amazon by 2030, Lula’s administration has introduced measures aimed at curbing forest loss such as designating new protected areas.

But, following pressures from powerful agribusinesses, states including Rondonia and Mato Grosso have recently approved new legislation that experts say could threaten a moratorium banning soy plantations in recently deforested areas.

Brazil is hosting this year’s UN COP30 climate summit – which has been dubbed the “forest COP” – in the Amazonian city of Belém.

“It’s shameful”: Amazon Indigenous people call for oil drilling ban at COP30

Neighbouring Bolivia saw primary forest loss skyrocket by 200% in 2024 – climbing to second place in the forest destruction ranking for the first time. The dramatic rise follows the government’s efforts to incentivise large-scale agricultural development through tax breaks and subsidies, experts said.

Stasiek Czaplicki Cabezas, a Bolivian forest researcher at Revista Nomadas, said the expansion of agro-industrial agriculture and cattle ranching into forested areas has been compounded by the widespread use of fire as a cheap method of clearing land.

“Laws exist, but enforcement is minimal. Deforestation is rarely sanctioned and oversight in frontier regions is almost entirely absent,” he added.

DRC conflict drives up forest loss

Forest destruction also continued in the Congo Basin last year, with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) marking its highest loss on record. Traditional drivers of deforestation in the region – such as reliance on forests for food and energy – have been exacerbated by military conflicts.

The Rwanda-backed M23 rebels have intensified their offensive in eastern DRC, grabbing large swathes of land. Battling between the government and rebel groups over natural resources has created instability and displacement of people, driving up forest loss, the report said.

DRC’s huge Green Corridor project lacks buy-in from forest communities

The annual survey’s only bright spot was Southeast Asia, with both Indonesia and Malaysia cutting forest loss last year by 11% and 13% respectively. Concerns remain, however, over the expansion of plantations and mining, especially in Indonesia where the newly-installed government is pushing for food and energy independence.

No progress on deforestation pledge

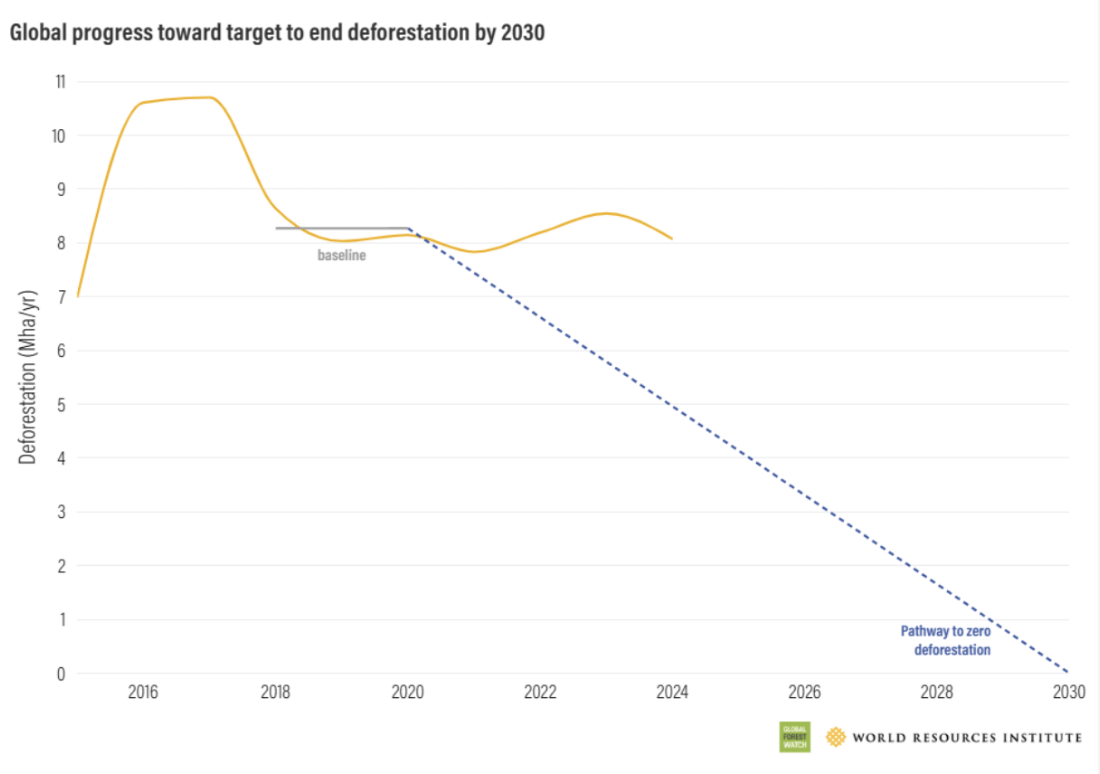

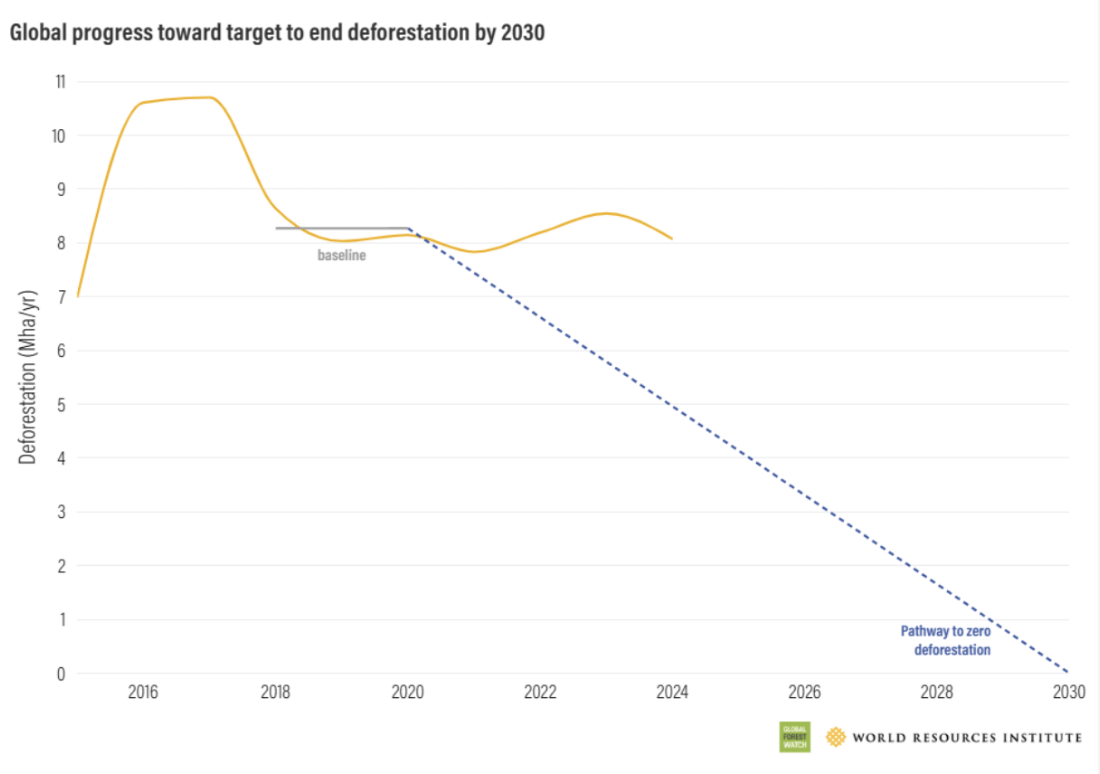

Four years ago, at COP26, 145 countries pledged to halt and reverse deforestation by 2030. That goal remains way off track as forest loss keeps rising while the world needs to reduce deforestation by 20% every year to honour that commitment.

“Of the 20 signees with the largest area of primary forest, 17 had higher primary forest loss in 2024 than when they signed the agreement in 2021,” said WRI’s Goldman.

Experts said the solutions to reverse this negative trend are known and include support for deforestation-free supply chains for commodities, better enforcement of trade regulations and increased funding for forest protection and fire prevention measures. But the political will to implement these is still missing.

Matt Hansen, a land use change expert at the University of Maryland, said this “frightening” data should not just spur concern but some form of action.

“Governance is the primary limitation and we have to influence those governments to act in the face of increasing threats to these ecosystems,” he added.