Data from the Indonesian government suggests efforts to restore peatlands, a key part of the country’s climate strategy, do not match government claims.

After devastating wildfires ravaged through Indonesia’s tropical peatlands in 2015 and left more than $16 billion in damages, the country launched an ambitious plan to restore this key ecosystem. This would be central to the government’s climate strategy.

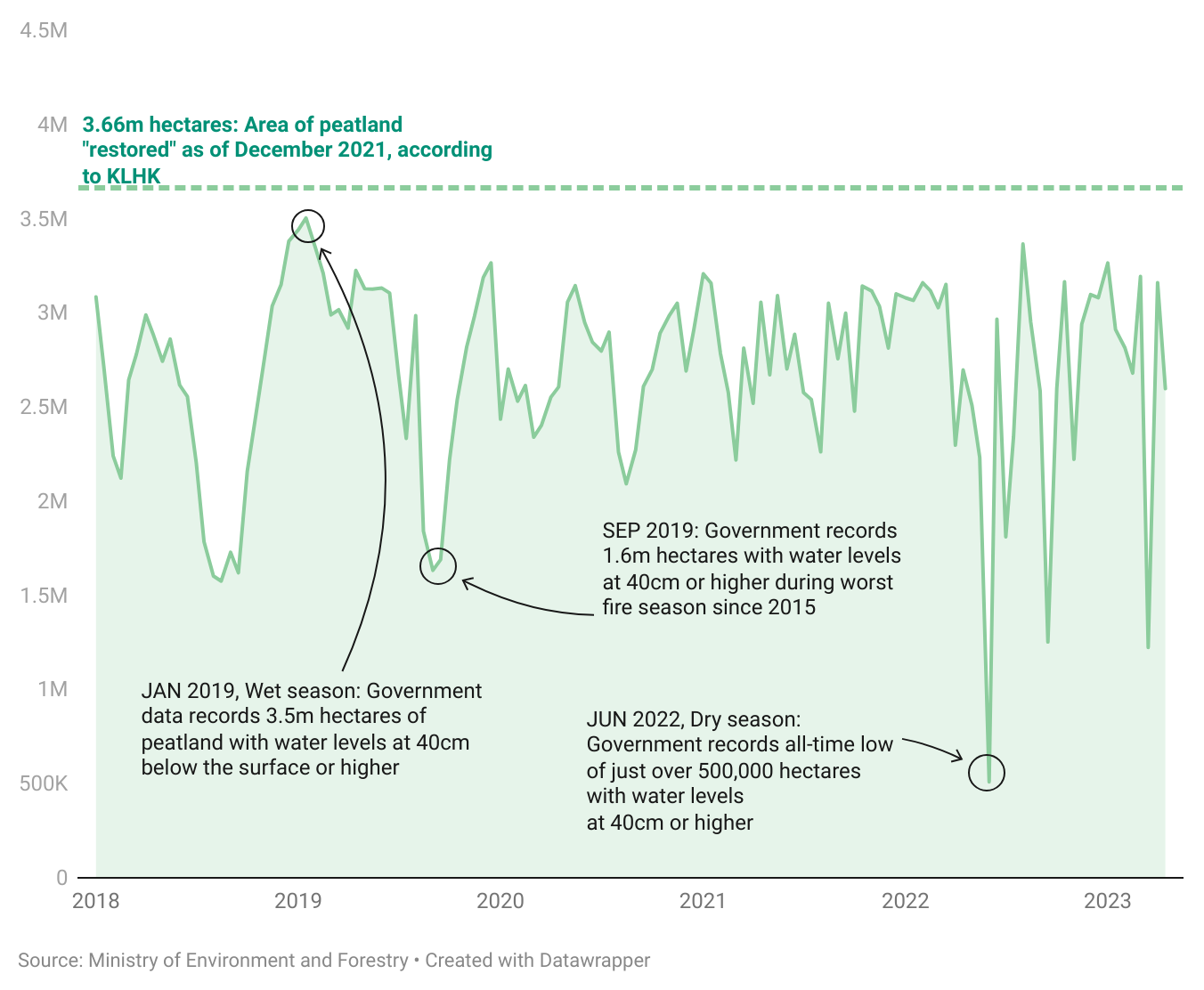

Eight years after, the Indonesian government claims to have made huge progress, with as much as 3.66 million hectares of peatland declared “restored” in areas managed by plantation companies. But these claims are not supported by data the government has made public, an analysis by The Gecko Project has found.

The government’s statements appear to hinge on a narrow definition of “restoration” that deems peatlands restored when groundwater levels have been raised to 40 centimetres below the surface.

The analysis of government data indicates that even by this measure, the areas “restored” have never reached the figures cited in official documentation and may in fact be far lower. Many of these peats sit on land licensed to timber companies.

The data also shows that the area of peatland that meets this 40cm threshold also fluctuates wildly as water levels rise and fall, sometimes dropping as low as half a million hectares – a fraction of the area claimed as “restored” by the government.

The Indonesian Ministry of Environment and Forestry, known as KLHK, did not respond to written questions, or to extensive attempts to seek comment on our findings.

Environmental researchers who spoke to The Gecko Project viewed the implementation of a system to monitor peatland restoration as a positive step. But some also expressed scepticism about the government’s claims of success and how it was arriving at its figures.

In the meantime, with Indonesia heading into what meteorologists predict could be an extreme dry season this year, the findings suggest that large areas of peatland could be far more vulnerable to burning than the government has acknowledged.

The coming months, said David Taylor, a professor and peatland expert at the National University of Singapore, would serve as “a good test” of the government’s claims.

An excavator operates in peatland covered by haze from fires in a concession belonging to PT Kaswari Unggul (KU) in Sumatra, Indonesia. (Photo: Greenpeace)

The repair job starts

Despite covering only around three percent of the planet’s land surface, peatlands store around a third of all the world’s soil carbon.

In Indonesia, where they cover more than 20 million hectares, peatlands have long been prone to fire during the dry season, especially during El Niño events. But the risks have been worsened by the draining of peatlands to allow cultivation of oil palm and timber plantations.

The government set out to undo some of that damage by issuing a series of decrees and regulations, beginning in 2016, which aimed to rewet drained peatlands and replant vegetation.

Gas lock-in: Debt-laden Ghana gambles on LNG imports

According to these guidelines, success would be assessed through multiple metrics, including plant growth and keeping the groundwater level at no lower than 40cm below the surface. Some research has suggested that higher water levels offer better protection against fires.

A specially-established government body, now named the Peatland and Mangrove Restoration Agency, or BRGM, was given authority for overseeing peat restoration in land controlled by communities or the government.

However, several million hectares of peatland fall within land already licensed to plantation companies. KLHK ordered companies to restore peatlands within their concessions and report back their progress.

Mission accomplished?

According to KLHK reports, companies have made progress in restoring peatlands. The KLHK website, for example, states that 3.4 million hectares of peatland within concession areas were “restored” between 2015 and 2019.

A more recent KLHK report from 2022 states that “as of December 2021 (peatland restoration) had reached 3.66 million hectares.”

But the KLHK’s methods for assessing which peatlands are restored can be narrow, experts say, as they appear to focus only on rewetting lands and not on other metrics.

While companies are required to raise peat groundwater levels to at least 40cm belowground, other phases of restoration work, such as replanting native vegetation, appear to have been sidelined, leaving “rewetting” to be used as a proxy for restoration.

In a 2022 report, the ministry registered fewer than 6,000 hectares as having “vegetation rehabilitation”.

“Green” finance bankrolls forest destruction in Indonesia

A data analysis by The Gecko Project also shows that, even under the more generous approach of counting only rewetted peatlands as restored, the numbers still fall short of what the government says has been restored.

Still, KLHK has claimed that by 2019, rewetting work alone had already reduced carbon dioxide emissions by more than 190 million tons – equivalent to the annual national emissions of the United Arab Emirates. KLHK did not respond to questions about the data supporting these calculations.

Restoration falls short?

KLHK has not made public a list of areas deemed to be restored and did not respond to requests for this information. However, it has published the areas that have been rewetted to various levels.

Using this data, The Gecko Project identified peatlands within concession areas and compared their water levels to the 3.66 million hectares that KLHK claims have been restored.

At a more detailed glance, the data shows big fluctuations in the “rewetted” area, suggesting that water levels are not being maintained on a stable basis.

For example, at the beginning of 2019, during a wet season that saw torrential floods in many parts of the country, KLHK registered that around 3.5 million hectares of peatland inside concession areas had groundwater levels at 40cm belowground or higher.

But in the middle of the 2022 dry season, the area rewetted was down to around just half a million hectares.

Fire risk

The data analysis also identified multiple “dry” concession areas in which water levels fell consistently below 40cm in the past year, highlighting a possibly heightened fire risk as this year’s El Niño event progresses.

As an example, PT Rimba Hutani Mas, a pulpwood plantation company and supplier of the major paper and pulp firm Asia Pulp & Paper (APP), manages nearly 70,000 hectares in South Sumatra province, the majority of which is on peatlands according to government maps.

Large sections of PT Rimba Hutani Mas’s peatland had water levels below the 40cm threshold over the last year, KLHK data shows. According to the ministry, concession holders that have groundwater at this level “should carry out field checks immediately and improve or repair water management infrastructure in the field.”

In 2015, army officers and firefighters try to extinguish fires in peatland areas outside the city of Palangka Raya in Borneo’s Central Kalimantan province. Photo: (Aulia Erlangga/CIFOR)

But the company was subject to legal action by Singapore’s National Environment Agency after evidence emerged that fires in its concession had contributed substantially to the haze of 2015. APP argued at the time that almost all the fires in its concession areas had been started outside those areas.

APP did not respond to specific questions about water levels in this supplier’s concession area. The company said it has been submitting “all the required data” to KLHK and pointed to its 2022 Sustainability Report.

Job not done

Peat researchers agree that fluctuations in water level are to be expected in peatlands, whether or not land is being managed. This complicates the use of groundwater level as a standalone measure of restoration success.

Water levels are highly dependent on external climate conditions, noted Muh Taufik, a tropical peatland researcher at IPB University. In the wet season, the water table could be at ground level or even above ground, while in the dry season it can fall to a metre or more below the surface, he said.

The topography of the land itself can influence the water table, too – valleys are more likely than slopes to remain wet. “It’s very difficult to maintain the water table around 40cm,” Taufik said.

Such variability reinforces some researchers’ concerns about judging restoration success on the basis of water level data alone.

As Guyana shows, carbon offsets will not save the Amazon rainforest

While getting water back into dried-out peatlands is important, “it’s definitely not ‘job done’” once the water table reaches 40cm, said Dominick Spracklen, a professor of biosphere-atmosphere interactions at the University of Leeds. Rather, he said, “it is a good proxy for things moving in the right direction.”

David Taylor, from the University of Singapore, suggested that rewetting should be seen as a first step.

While having a monitoring system for peat rewetting is a positive step, he said, it’s important to take a more holistic approach to peat restoration that acknowledges the time and multiple steps involved – particularly reintroducing plants and allowing natural vegetation to grow in the absence of peat-damaging plantation activities.

Uncertain figures

Gusti, the professor at Tanjungpura University said it’s “very complicated” to determine whether the ministry’s peatland restoration claims have been achieved or not.

Separate KLHK documents appear to acknowledge much lower success rates than claimed by officials. A 2020 report, for example, noted that, out of 280 concession areas, just 60 were found to have “actually improved their performance of peatland ecosystems management.”

Fieldwork published in 2021 by the nonprofit Pantau Gambut concluded that “most companies” had failed to implement plans to restore peat.

The implications of these failings, and the fluctuations in water levels, may become apparent in the coming months, as dry weather continues to intensify in Indonesia in the first El Niño year since 2019.1 By mid-June, KLHK reported that fires in 2023 had already affected more than 28,000 hectares of forest and other land.

“Big El Niños over the last thirty years or so have been associated with drought here in southeast Asia [and with] peatland fires,” said Taylor.

Fires can burn even on pristine peatlands, he said, but if Indonesia’s restoration work has been successful, it should help limit some of the damage. “I think it’s going to be a test of claims that have been made that these peatlands have been restored.”

This story was published in partnership with The Gecko Project.