A 1920s science headline, “Ice cream from crude oil,” may best capture the era’s unbridled enthusiasm for chemistry. “Edible fats, the same as those in vegetable and animal foods … and equally nutritious … can be obtained by breaking up the molecules of mineral oil and rearranging the atoms,” exclaimed Science News Letter, the predecessor to Science News, in 1926. Synthetic ice cream was just one of the wonders that could lie around the corner.

Petroleum would become increasingly valuable, the article continued, “as a source of substances for which man has hither-to been dependent upon the chance bounty of nature.” A rash of potential products included aromatics, flavorings, nitroglycerin for dynamite, plastics, drugs and more.

Petroleum-based ice creams never became the new big thing, yet the last century has witnessed a dramatic leap in humans’ ability to synthesize matter. From our homes and cities to our electronics and clothing, much of what we interact with every day is made possible through the manipulation, recombination and reimagination of the basic substances nature has provided.

To celebrate our 100th anniversary, we’re highlighting some of the biggest advances in science over the last century. To see an expanded version of this story and more from the series, visit Century of Science.

READ MORE

“The world is unrecognizable from 100 years ago,” says Anna Ploszajski, a materials scientist and author of the 2021 book Handmade: A Scientist’s Search for Meaning Through Making. And that, she says, is “simply because of the materials that we have around, let alone all of the new ways we use them.”

At the turn of the 20th century, organic chemists learned how to turn coal into a variety of industrial chemicals, including dyes and perfumes. Later, motivated by wartime demand, chemists honed their craft with poison gas, explosives and propellants, as well as disinfectants and antiseptics. As a result, World War I was often called “the chemist’s war.” And at a fundamental level, the new century also ushered in greater understanding of chemical bonds and the atom, its constituents and its behavior.

In the decades that followed, approaches in chemistry and physics combined with engineering to give rise to a new field, now called materials science. An extensive survey of the field, put together by the National Academy of Sciences in the 1970s and titled “Materials and Man’s Needs,” described the pace of research: “The transitions from, say, stone to bronze and from bronze to iron were revolutionary in impact, but they were relatively slow in terms of the time scale. The changes in materials innovation and application within the last half century occur in a time span which is revolutionary rather than evolutionary.”

Alongside this new science came new and improved scientific tools. Scientists can now see materials at a much finer scale, with the electron microscope making individual atoms visible. X-ray crystallography unveils atomic arrangements, allowing for a better understanding of materials’ structure. With equipment such as chromatographs and mass spectrometers, today’s scientists can untangle mixtures of chemicals and identify the compounds within. Francis Aston first took advantage of a mass spectrometer in his study of isotopes in 1919, but for a long time the tool was seen by some chemists as, according to a description by mass spectrometrist Michael Grayson, “an unexplainable, voodoo, black magic kind of a tool.”

Many new materials were birthed from basic curiosity and serendipity. But new techniques also made way for targeted innovation. Today, materials can be designed from scratch to solve specific problems. And explorations of the properties of solid substances — for instance, how matter interacts with heat, light, electricity or magnetism — along with iterations of design have further contributed to the stuff that surrounds us, giving way to transistors, eyeglass lenses that darken in sunlight, touch screens and hard disk drives. Explorations into how matter interacts with biological tissues have yielded coronary stents, artificial skin and hip replacements that include metal mélanges that are tough and nonreactive when they sit against bone.

The outputs of such efforts are all around us. Take air travel, and the global interconnectivity it introduced. It’s possible thanks to alloys that are lightweight and robust. And today’s personal connectivity — via smartphones and computers — came with transistors made of silicon. Their small size and low power requirements brought computing to our office desks, and then into our homes and pockets. An abundance of plastic housewares and comfy athleisure clothing options are made possible via improvements in polymers.

Yet innovation hasn’t come without consequences. For each tale of progress, there are stories of the marks people have left on this planet. While enabling humans to flourish, many new substances have become pollutants, from PCBs to plastics. However people go about addressing these environmental problems, other new materials will likely be part of the solutions.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Going places

It was the summer of 1940, the early days of the Battle of Britain. Nazi Germany’s air force, the Luftwaffe, began a months-long attack on the British Isles that eventually included the nightly bombing raids known as the Blitz. Going into the battle, the Luftwaffe believed it had the upper hand; in battles in France, the Germans had dominated in the air. Little did they know the Allies had a secret weapon — in their fuel tanks.

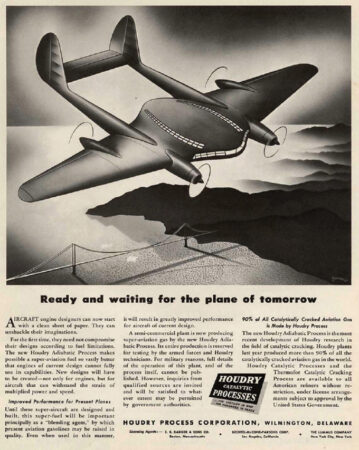

As Germans began flying over England, they were surprised to find the tables had turned. The British Spitfires and Hurricanes that the Germans had outmaneuvered in France could now climb higher and fly faster thanks to fuel made with a newly developed process called catalytic cracking.

Catalysts boost chemical reactions by reducing the energy needed to get them going. French mechanical engineer Eugene Houdry had developed a catalytic process in the 1930s to make high-octane fuel, which can withstand higher compression and allows engines to deliver more power. Simply increasing the octane rating of aviation fuel from 87 to 100 gave the Allies a crucial edge.

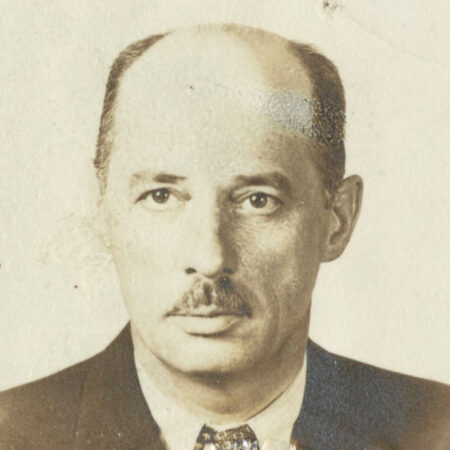

French mechanical engineer Eugene Houdry developed catalytic cracking in the 1930s.From Left: Courtesy of Science History Institute

French mechanical engineer Eugene Houdry developed catalytic cracking in the 1930s.From Left: Courtesy of Science History Institute

Houdry wasn’t the first to attempt using catalysts to bust the big molecules of heavy fuels into smaller ones to improve performance. But as an avid road racer, he had a special interest in high-quality gasoline. He studied hundreds of catalysts until he landed on aluminum- and silicon-based materials that could do the busting more efficiently than an existing process that relied on heat. When he tested his gasoline in his Bugatti racer, he reached speeds of 90 miles per hour.

In the following decades, catalytic cracking and improvements to the process Houdry pioneered would contribute to the reign of automobiles. Catalytic cracking still produces much of the gas that cars guzzle today.

But all that driving soon took a toll on the environment. When the hydrocarbon molecules in gasoline burn, the engine exhaust contains small amounts of harmful gases: poisonous carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide that can cause smog and acid rain, as well as unburned hydrocarbons. Los Angeles and other car-packed cities choked on smog in the 1940s and ’50s.

Houdry looked again to catalysts to deal with the pollution that internal combustion engines caused. He designed a catalytic converter.

“When first considered, the problem seems simple,” Houdry wrote in a 1954 patent application. “A great number of catalysts can be used for the reaction. By simply placing one of these catalysts in the exhaust line under controlled conditions, the exhaust fumes can be cleaned.” The catalysts, precious metals such as platinum or palladium, provide docking sites for the harmful gases to hang onto; there, reactions involving oxygen convert them to less harmful forms.

This 1940s ad says that 90 percent of all aviation fuel made by catalytic cracking came from the Houdry Process Corporation.Retro Adarchives/Alamy Stock Photo

This 1940s ad says that 90 percent of all aviation fuel made by catalytic cracking came from the Houdry Process Corporation.Retro Adarchives/Alamy Stock Photo

In the 1950s, Houdry outlined a series of reactions, materials and conditions necessary for a working catalytic converter. But he was ahead of his time. For years, the adoption of catalytic converters in automobiles was stymied by leaded gasoline, which gummed up the catalysts’ surfaces. Finally, with the passage of the Clean Air Act of 1970, which led to requirements for catalytic converters and lead-free fuel, the air in cities began to clear.

For air travel to serve the masses, a different dilemma needed solving: lightening the load. The earliest airplanes gained lift at the turn of the 20th century on wings of fabric and wood, but to really soar, airplanes needed light but strong materials. The first aircraft designed for passengers — the Ford Trimotor, nicknamed the Tin Goose — took to the air in 1926 with help from aluminum alloys.

Alloys have existed since ancient times. Bronze Age artisans combined copper with arsenic or tin in crucibles to make tools, jewelry and more. From there, advances coincided with the ability to melt metals at higher and higher temperatures, eventually leading to steel. Scientists since have studied how materials’ structures and properties — including desirable features like strength, bendability and resistance to corrosion — vary with composition, temperature and processing.

The fuselage of the Tin Goose contained a newly developed alloy named duralumin, a contraction of “Dürener” (for the company that originally made it) and “aluminum.”

In 1926, Science News Letter described the promise of materials such as duralumin for safer dirigibles, which would carry large numbers of passengers into the air: “Of these sound materials, strong and light girders must be built. So light that a man can carry one of them in his hand and yet so strong that they will carry loads of thousands of pounds.”

Dirigibles and duralumin were just the beginning. The 20th century saw an explosion in the types of alloys and their applications, from stainless steel cutlery to the titanium alloys used in prostheses and pacemakers to crucial components of vehicles. Today’s jet engines are built of superalloys, which can withstand infernal temperatures.

Plastics and composites have also helped planes shed weight. Composites combine materials with very different properties — such as glass and plastic — by suspending one in the other or sandwiching them together, for instance. Because they can be tuned to be light and strong, composites have made their way into parts all over planes, from the engine to the wings. Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner, which debuted in 2007, is made up of 50 percent composites by weight.

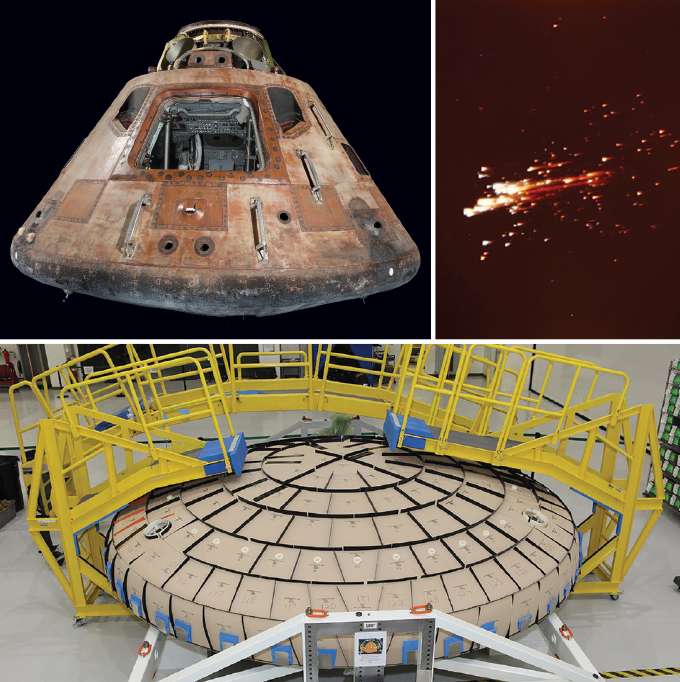

Astronauts in the Apollo 11 command module (top left) were protected from high temperatures during re-entry through Earth’s atmosphere (center) by a heat shield made of Avcoat, a reinforced plastic made from an epoxy resin within a honeycomb fiberglass network. A new NASA spaceship called Orion, destined to take people to the moon and beyond, uses Avcoat tile blocks bonded onto its heat shield (bottom).From top left: Smithsonian Institution, transferred from NASA; NASA; NASAAstronauts in the Apollo 11 command module (left) were protected from high temperatures during re-entry through Earth’s atmosphere (center) by a heat shield made of Avcoat, a reinforced plastic made from an epoxy resin within a honeycomb fiberglass network. A new NASA spaceship called Orion, destined to take people to the moon and beyond, uses Avcoat tile blocks bonded onto its heat shield (right).From left: Smithsonian Institution, transferred from NASA; NASA; NASA

Astronauts in the Apollo 11 command module (top left) were protected from high temperatures during re-entry through Earth’s atmosphere (center) by a heat shield made of Avcoat, a reinforced plastic made from an epoxy resin within a honeycomb fiberglass network. A new NASA spaceship called Orion, destined to take people to the moon and beyond, uses Avcoat tile blocks bonded onto its heat shield (bottom).From top left: Smithsonian Institution, transferred from NASA; NASA; NASAAstronauts in the Apollo 11 command module (left) were protected from high temperatures during re-entry through Earth’s atmosphere (center) by a heat shield made of Avcoat, a reinforced plastic made from an epoxy resin within a honeycomb fiberglass network. A new NASA spaceship called Orion, destined to take people to the moon and beyond, uses Avcoat tile blocks bonded onto its heat shield (right).From left: Smithsonian Institution, transferred from NASA; NASA; NASA

Making connections

For a testament to the power of materials to connect us, just look at an iPhone. “The iPhone contains about 75 elements from the periodic table — a huge proportion of all the atoms that we know about in the universe are in an iPhone,” says Ploszajski, the materials scientist.

Some of those are rare-earth elements, a set of 17 metallic elements mostly on the outskirts of the periodic table. Though they are difficult to mine and process, rare earths are sought after because they lend unusual magnetic, fluorescent and electrical properties to materials made from them. Neodymium, for example, mixed with other metals makes the strongest magnets known. These magnets make your cell phone vibrate and its speakers produce sound.

Despite the hazards associated with mining them, these elements show up in a lot of other 20th century applications too. Rare earths are in color televisions, camera lenses, fiber-optic cables, nuclear reactors, nickel-metal hydride batteries, aircraft engines, PET scanners and much more.

Peter Dazeley/The Image Bank/Getty Images

Peter Dazeley/The Image Bank/Getty Images

The iPhone contains about 75 elements from the periodic table — a huge proportion of all the atoms that we know about in the universe are in an iPhone.

Anna Ploszajski

A more familiar element — silicon — is the reason cell phones and laptops are available in such a widespread way.

As a semiconductor, silicon conducts electricity better than ceramics and glass do, but not as well as metals. This in-between status makes it possible to control how electrons zip around a semiconductor, a control that’s ideal for creating electrical switches for circuits in radios, televisions or computers. In the 1930s and ’40s, these and other electronic devices relied on bulky, breakable glass vacuum tubes to control electric current flow. Decades of semiconductor research pointed to a more reliable, slimmer way.

The first semiconductor switch, dubbed the transistor, was made of germanium and invented at Bell Laboratories in 1947. But teams at Texas Instruments and Bell Labs were both eyeing silicon, which holds up under higher temperatures. Silicon is also less likely than germanium to leak current when a switch is off. Though the two teams independently developed silicon transistors, Texas Instruments’ Gordon Teal gets the credit as his announcement came first, in May 1954.

In 1948, Science News Letter reported that “the glass vacuum tube in your radio has its first rival in 40 years”: a germanium transistor.Science News Letter

In 1948, Science News Letter reported that “the glass vacuum tube in your radio has its first rival in 40 years”: a germanium transistor.Science News Letter

At a conference in Dayton, Ohio, toward the end of the day’s talks, Teal matter-of-factly revealed his company’s success. “Contrary to what my colleagues have told you about the bleak prospects for silicon transistors,” he said, “I happen to have a few of them here in my pocket.” His announcement, which followed other talks suggesting that the devices were years away, jolted the audience, which stampeded to the back of the room for copies of Teal’s talk, and out to the telephone booth to share the news.

Our attention-sucking phones are right in front of our faces. But out of sight are the fiber optics that relay messages around the world in a flash.

All the glass strung out in the world’s optical cables could tether Earth to Uranus and then some, stretching some 4 billion kilometers. These cables ferry messages across countries and continents and across the seafloor. Optical fiber “really has strung the world together in a new way,” says Ainissa Ramirez, a materials scientist and author of the 2020 book The Alchemy of Us (SN: 4/25/20, p. 28). Messages from across the Atlantic used to come by boat, she says, then came copper cables to relay telegraph dispatches in the 1840s. The first live telephone traffic sent through fiber-optic cables was in 1977 in Long Beach, Calif. Now e-mails from abroad arrive nearly instantaneously thanks to thin-as-hair optical fibers.

The list of materials that helped put oceans of information at our fingertips goes on and on. All of these developments, including today’s lithium-ion batteries and more, led to today’s abundance of electronic devices (SN: 1/21/17, p. 22). But ever more improvements, and our constant urge to upgrade, creates a new problem: “How do we unmake this stuff and recycle those substances safely?” Ploszajski asks.

Google’s Dunant subsea cable connects Virginia Beach with France (it’s shown landing on the French coast in 2020) and can deliver 250 terabits per second across the Atlantic Ocean.Mario Fourmy/Sipa via AP Images

Google’s Dunant subsea cable connects Virginia Beach with France (it’s shown landing on the French coast in 2020) and can deliver 250 terabits per second across the Atlantic Ocean.Mario Fourmy/Sipa via AP Images

A plethora of plastic

In a quest to really grasp the omnipresence of plastics, Susan Freinkel, author of the 2011 book Plastic: A Toxic Love Story, pledged to go a day without touching any. Glimpsing her plastic toilet seat, Freinkel gave up the experiment mere moments after it began. Instead, she spent the day cataloging all the plastic stuff she encountered.

Plastics covered her body — in yoga pants, sneakers and eyeglasses. Plastic made up the entire interior of her minivan and parts of kitchen appliances. Plastic packaging protected her food, and after eating, she dumped her trash in a plastic bin. Even the walls around her contained plastics, from the paint to the synthetic insulation.

Today, we’re awash in plastics. Yet at the beginning of the 20th century, only a handful of plastics had made their way into homes.

The story of commercial plastics began in the 1860s, when John Wesley Hyatt, seeking a substitute for the ivory popularly used in billiard balls, landed on a material later called celluloid. At the heart of celluloid, however, was the natural substance cellulose.

The first fully synthetic plastic, Bakelite, arrived in 1907. It was a fluke discovery by Belgian-born chemist Leo Baekeland, who was seeking an alternative to the natural shellac that insulated electrical cables. Celluloid was a suitable substitute for ivory and tortoiseshell, but sleek, shiny Bakelite gleamed with modernity. It quickly made its way into a host of products, including the casings for radios, jewelry and telephones. A new era of innovating on nature’s materials, rather than merely mimicking them, was born, Freinkel writes.

Yet it wasn’t until the 1920s that researchers started to understand plastics’ chemical nature. Plastics are made of polymers, large molecules made of repeating units. At the time, what gave natural polymers like cellulose, shellac and rubber their properties remained unknown. So inventors seeking new human-made substitutes relied on trial and error to make something similar. Credit for changing all that goes to the German organic chemist Hermann Staudinger.

From experiments on natural rubber, Staudinger showed that large, heavy molecules could be formed by linking many smaller molecules into chains. As Science News Letter put it in 1953, when Staudinger was awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry: “The way the molecules regiment themselves determines the differences between springy rubber, hard plastic and tough fiber.” It might sound obvious today, but Staudinger’s finding was controversial. Chemists at the time thought that what we now call macromolecules were simply aggregates of smaller molecules.

In the 1920s, German chemist Hermann Staudinger showed that small molecules can link up in chains to form very large molecules. The discovery helped set the stage for a boom in synthetic materials, including plastics.Eth-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv, Fotograf: Unbekannt, Portr_14413-016-Al, Public Domain Mark

In the 1920s, German chemist Hermann Staudinger showed that small molecules can link up in chains to form very large molecules. The discovery helped set the stage for a boom in synthetic materials, including plastics.Eth-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv, Fotograf: Unbekannt, Portr_14413-016-Al, Public Domain Mark

Staudinger’s ideas gradually gained acceptance and formed a basis for new research on polymers. In the following decade, industrial chemists worked to figure out the chemical reactions needed to create new polymers, plastics among them. One early success story was nylon, a carbon-based polymer patented in 1938 as a substitute for silk. American women were introduced to nylon stockings in 1940. Within a year, nylons grabbed 30 percent of the hosiery market.

But it was World War II that drastically increased demand for plastics. The military turned to the new industry to make substitutes for strategic materials such as glass, brass or steel, Freinkel says. Nylon was needed for military uses, so women offered up their stockings to be recycled.

“Great piles of stockings retired after faithful and intimate service are awaiting resurrection — thousands of pounds of them,” reported Science News Letter in 1943.

Though small at the start of the war, the plastics industry got better at making its wares and boosted production. Processes such as injection molding, which spurts melted plastic into a mold “sort of like a Play-Doh Fun Factory,” Freinkel says, made it possible to mass-produce plastic. A technique called blow molding, invented in the 1930s and based on the same principle as glass blowing, offered a quick way to form plastic bottles.

As wartime demand dried up, the plastics industry began to bring its products to the people. “You start to get this flood of plastic into everyday life,” Freinkel says.

The promise of plastic was on display in 1946. Held in New York City, the first National Plastics Exhibition featured wares made of the wonder material. “Thousands of people lined up to go to this trade show and walk through this conference hall and gawk at stuff that had an almost magical quality,” Freinkel says. Visitors saw durable nylon fishing line and window screens in a riot of colors. Mass-produced plastic offered “a new way to have the good life on the cheap.”

We’ve come a long way from the days of celluloid and Bakelite. Tens of thousands of plastic compounds exist today. The world now produces in excess of 380 million metric tons of plastic a year — that’s more than a hundred pounds of what’s typically very lightweight stuff for every person on the planet every year.

Consequences

By the mid-1960s, researchers started noticing plastic pieces in the ocean, Freinkel says. Today, plastic pollution is found virtually everywhere, in bits wafting in the winds, high in Mount Everest’s snow and as trash piling up on the seafloor.

Plastics are the quintessential example of the journey from material marvel to environmental nuisance. But they’re not the only problem.

The organic chemistry advances of the early 1900s made new and exciting materials possible, but also allowed people to make more and more materials that weren’t recyclable, says Thomas Le Roux, a historian at the French National Center for Scientific Research in Paris and co-author of the 2020 book The Contamination of the Earth. By the 1970s, new disposable products, from pens to razors to packaging, signaled an ease of life. “It was modern to throw away what we buy,” he says.

The consequences of this easy-come, easy-go relationship with our stuff soon appeared in the environment. Our unabated demand for fossil fuels, used not only as fuel but as raw materials for making plastics, releases emissions that contribute to Earth’s changing climate.

Plastics, which help make modern life convenient, are polluting lakes, rivers and oceans, as shown here on the beach of Costa del Este in Panama City.LUIS ACOSTA/AFP VIA GETTY Images

Plastics, which help make modern life convenient, are polluting lakes, rivers and oceans, as shown here on the beach of Costa del Este in Panama City.LUIS ACOSTA/AFP VIA GETTY Images

Many of our modern substances were created to solve problems, says Mark Jones, a chemist and member of the National Historic Chemical Landmarks committee of the American Chemical Society. For instance, before the 1930s, air conditioning and refrigeration relied on ammonia, which is flammable and toxic. That changed with the introduction of Freon and other chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs for short, which were created by chemists in the 1920s. These molecules appeared to have little effect on living things. “They were presumed to be incredibly safe,” says Jones, who recently retired from Dow Chemical.

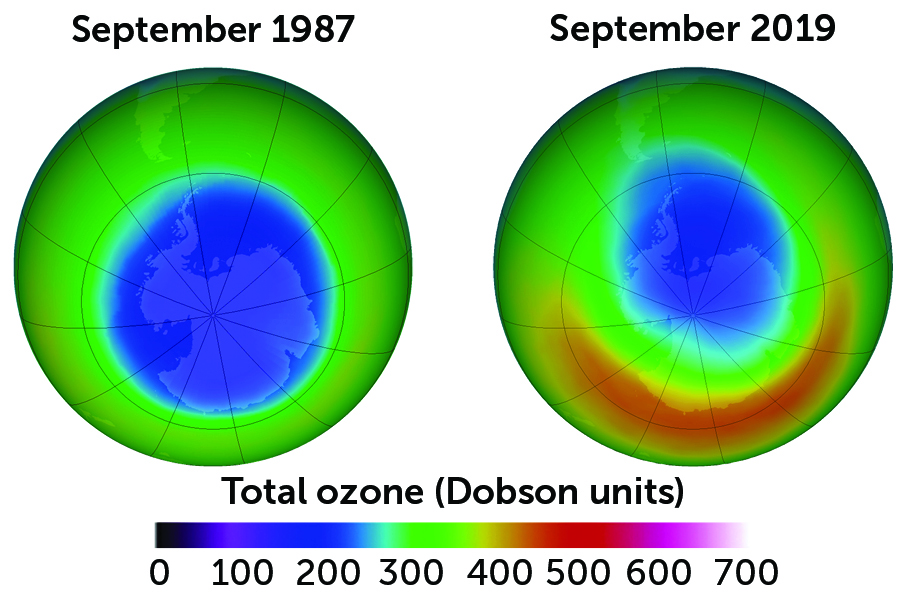

But Freon and its CFC cousins had unforeseen consequences on the atmosphere when they escaped air conditioning and refrigeration systems. In the 1980s, scientists discovered a hole in Earth’s ozone layer that forms when CFCs rise to the stratosphere, break down and react with ozone, destroying it. In solving one problem, humankind found itself with another.

CFCs’ creation

In 1985, scientists discovered a hole in the ozone layer, created by chlorofluorocarbons in the stratosphere. The Montreal Protocol turned things around: 2019 saw the smallest ozone hole ever recorded (compared below with 1987).

NASA Ozone WatchNASA Ozone Watch

NASA Ozone WatchNASA Ozone Watch

The history of science offers up abundant examples of solutions begetting new problems. Polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, useful insulators in electronics, can cause serious health problems, including cancer, when they enter the environment. The compounds that allow food to slide out of kitchen pans without sticking belong to a family that has earned the title “forever chemicals” for the tendency not to degrade. Lithium mining, which has increased with demand for lithium-ion batteries, guzzles water and can release harmful chemicals that contaminate ecosystems and poison drinking wells. Other battery ingredients, such as cobalt, are mined unethically — sometimes using child labor.

Perhaps the largest unintended consequence that humankind faces today is climate change. Human activities — factories, mining, growing food, traveling, using air conditioning and heating to keep indoor climates comfortable — have released greenhouse gas emissions that have heated the world by around 1.25 degrees Celsius since preindustrial times. The world is already experiencing extreme weather events linked to climate change.

380+

million metric tons

Amount of plastic produced per year

Clearly chemists and materials scientists have contributed to these problems. But they will inevitably be part of finding solutions as well. There’s a cyclical nature to the promise and perils of new molecules and materials. “The entire history of chemistry is, ‘Hey, look what I can do! Darn, I wish I hadn’t done it that way! But I have another way I can do it.’ And that keeps us kind of moving forward,” Jones says.

Chemists are now creating plastics that will break down after use and can be recycled more easily (SN: 1/30/21, p. 20). Materials scientists are developing better membrane materials to filter pollutants out of water (SN: 11/24/18, p. 18). Engineers are deploying new materials to capture carbon dioxide at smokestacks.

New iron-based catalysts could someday convert captured carbon dioxide into jet fuel, potentially cutting greenhouse gas emissions from air travel (SN: 1/30/21, p. 5). And researchers continue to innovate to turn more and more of the solar spectrum into energy, and so cut our reliance on fossil fuels (SN: 8/5/17, p. 22).

Chemistry and materials innovation can’t solve all our problems. People’s choices also matter. Weighing the risks and rewards that come with new materials will require recognition of the potential problems, regulations to combat them, willpower, collaboration and collective action. History holds plenty of lessons, but it’s not yet clear whether we’ll learn from them.