In the middle of the 20th century, the field of psychology had a problem. In the wake of the Manhattan Project and in the early days of the space race, the so-called “hard sciences” were producing tangible, highly publicized results. Psychologists and other social scientists looked on enviously. Their results were squishy, and difficult to quantify.

Psychologists in particular wanted a statistical skeleton key to unlock true experimental insights. It was an unrealistic burden to place on statistics, but the longing for a mathematical seal of approval burned hot. So psychology textbook writers and publishers created one, and called it statistical significance.

By calculating just one number from their experimental results, called a P value, researchers could now deem those results “statistically significant.” That was all it took to claim — even if mistakenly — that an interesting and powerful effect had been demonstrated. The idea took off, and soon legions of researchers were reporting statistically significant results.

To celebrate our 100th anniversary, we’re highlighting some of the biggest advances in science over the last century. For more on the history of psychology, visit Century of Science: The science of us.

READ MORE

To make matters worse, psychology journals began to publish papers only if they reported statistically significant findings, prompting a surprisingly large number of investigators to massage their data — either by gaming the system or cheating — to get below the P value of 0.05 that granted that status. Inevitably, bogus findings and chance associations began to proliferate.

As editor of a journal called Memory & Cognition from 1993 to 1997, Geoffrey Loftus of the University of Washington tried valiantly to yank psychologists out of their statistical rut. At the start of his tenure, Loftus published an editorial telling researchers to stop mindlessly calculating whether experimental results are statistically significant or not (SN: 5/16/13). That common practice impeded scientific progress, he warned.

Keep it simple, Loftus advised. Remember that a picture is worth a thousand reckonings of statistical significance. In that spirit, he recommended reporting straightforward averages to compare groups of volunteers in a psychology experiment. Graphs could show whether individuals’ scores covered a broad range or clumped around the average, enabling a calculation of whether the average score would likelychange a little or a lot in a repeat study. In this way, researchers could evaluate, say, whether volunteers scored better on a difficult math test if first allowed to write about their thoughts and feelings for 10 minutes, versus sitting quietly for 10 minutes.

Loftus might as well have tried to lasso a runaway train. Most researchers kept right on touting the statistical significance of their results.

“Significance testing is all about how the world isn’t and says nothing about how the world is,” Loftus later said when looking back on his attempt to change how psychologists do research.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

What’s remarkable is not only that mid-20th century psychology textbook writers and publishers fabricated significance testing out of a mishmash of conflicting statistical techniques (SN: 6/7/97). It’s also that their weird creation was embraced by many other disciplines over the next few decades. It didn’t matter that eminent statisticians and psychologists panned significance testing from the start. The concocted calculation proved highly popular in social sciences, biomedical and epidemiological research, neuroscience and biological anthropology.

A human hunger for certainty fueled that academic movement. Lacking unifying theories to frame testable predictions, scientists studying the mind and other human-related topics rallied around a statistical routine. Repeating the procedure provided a false but comforting sense of having tapped into the truth. Known formally as null hypothesis significance testing, the practice assumes a null hypothesis (no difference, or no correlation, between experimental groups on measures of interest) and then rejects that hypothesis if the P value for observed data came out to less than 5 percent (P < .05).

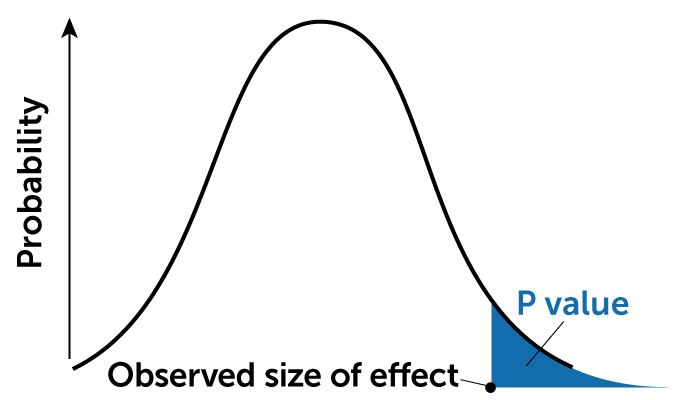

P value

A P value is the probability of an observed (or more extreme) result arising only from chance.

E. Otwell

E. Otwell

The problem is that slavishly performing this procedure absolves researchers of having to develop theories that make specific, falsifiable predictions — the fundamental elements of good science. Rejecting a null hypothesis doesn’t tell an investigator anything new. It only creates an opportunity to speculate about why an effect might have occurred. Statistically significant results are rarely used as a launching pad for testing alternative explanations of those findings.

Psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer, director of the Harding Risk Literacy Center in Berlin, considers it more accurate to call null hypothesis significance testing “the null ritual.”

Here’s an example of the null ritual in action. A 2012 study published in Science concluded that volunteers’ level of religious belief declined after viewing pictures of Auguste Rodin’s statue The Thinker, in line with an idea that mental reflection causes people to question their faith in supernatural entities. In this study, the null hypothesis predicted that volunteers’ religious beliefs would stay the same, on average, after seeing The Thinker, assuming that the famous sculpture has no effect on viewers’ spiritual convictions.

The null ritual dictated that the researchers calculate whether group differences in religious beliefs before and after perusing the statue would have occurred by chance in no more than one out of 20 trials, or no more than 5 percent of the time. That’s what P < .05 means. By meeting that threshold, the result was tagged statistically significant, and not likely due to mere chance.

If that sounds reasonable, hold on. Even after meeting an arbitrary 5 percent threshold for statistical significance, the study hadn’t demonstrated that statue viewers were losing their religion. Researchers could only conjecture about why that might be the case, because the null ritual forced them to assume that there is no effect. Talk about running in circles.

To top it off, an independent redo of The Thinker study found no statistically significant decline in religious beliefs among viewers of the pensive statue. Frequent failures to confirm statistically significant results have triggered a crisis of confidence in sciences wedded to the null ritual (SN: 8/27/18).

Some journals now require investigators to fork over their research designs and experimental data before submitting research papers for peer review. The goal is to discourage data fudging and to up the odds of publishing results that can be confirmed by other researchers.

11

percent

Percentage of ‘landmark’ cancer studies that a biotechnology firm was able to replicate over a decade (6 of 53)

Source: C.G. Begley and L.M. Ellis/Nature 2012

But the real problem lies in the null ritual itself, Gigerenzer says. In the early 20th century, and without ever calculating the statistical significance of anything, Wolfgang Köhler developed Gestalt laws of perception, Jean Piaget formulated a theory of how thinking develops in children and Ivan Pavlov discovered principles of classical conditioning. Those pioneering scientists typically studied one or a handful of individuals using the types of simple statistics endorsed decades later by Loftus.

From 1940 to 1955, psychologists concerned with demonstrating the practical value of their field, especially to educators, sought an objective tool for telling real from chance findings. Rather than acknowledging that conflicting statistical approaches existed, psychology textbook writers and publishers mashed those methods into the one-size-fits-all P value, Gigerenzer says.

One inspiration for the null ritual came from British statistician Ronald Fisher. Starting in the 1930s, Fisher devised a type of significance testing to analyze the likelihood of a null hypothesis, which a researcher could propose as either an effect or no effect. Fisher wanted to calculate the exact statistical significance associated with, say, using a particular fertilizer deemed promising for crop yields.

Around the same time, statisticians Jerzy Neyman and Egon Pearson argued that testing a single null hypothesis is useless. Instead, they insisted on determining which of at least two alternative hypotheses best explained experimental results. Neyman and Pearson calculated an experiment’s probability of accepting a hypothesis that’s actually true, something left unexamined in Fisher’s null hypothesis test.

Psychologists’ null ritual folded elements of both approaches into a confusing hodge-podge. Researchers often don’t realize that statistically significant results don’t prove that a true effect has been discovered.

And about half of surveyed medical, biological and psychological researchers wrongly assume that finding no statistical significance in a study means that there was no actual effect. A closer analysis may reveal findings consistent with a real effect, especially when the original results fell just short of the arbitrary cutoff for statistical significance.

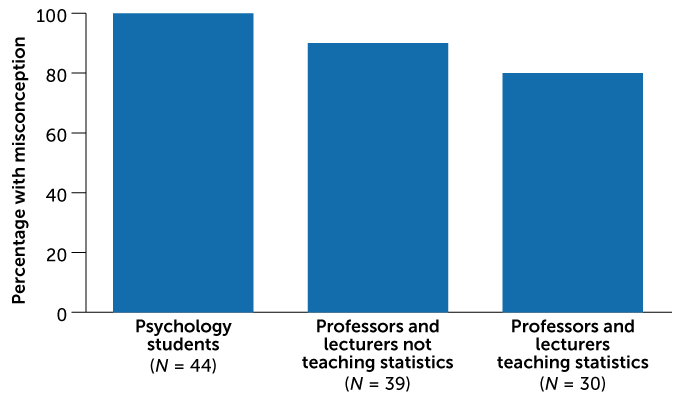

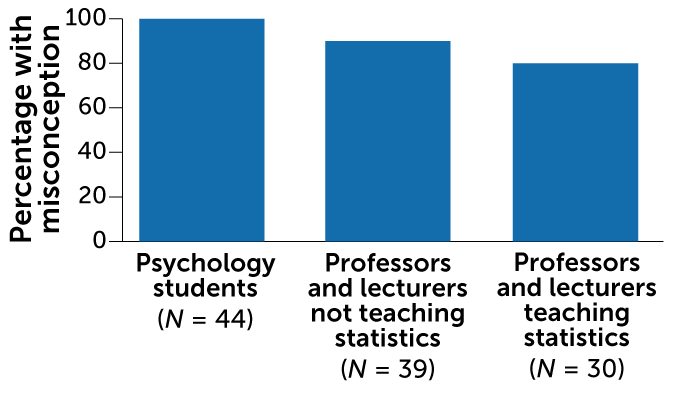

Statistical errors

A study of German psychology professors and students found that most agreed with at least one false statement about the meaning of a P value.

Frequency of misconceptions about P values  G. Gigerenzer/The Journal of Socio-Economics2004, adapted by E. Otwell

G. Gigerenzer/The Journal of Socio-Economics2004, adapted by E. Otwell  G. Gigerenzer/The Journal of Socio-Economics 2004, adapted by E. Otwell

G. Gigerenzer/The Journal of Socio-Economics 2004, adapted by E. Otwell

It’s well past time to dump the null ritual, says psychologist and applied statistician Richard Morey of Cardiff University, Wales. Researchers need to focus on developing theories of mind and behavior that lead to testable predictions. In that brave new scientific world, investigators will choose which of many statistical tools best suits their needs. “Statistics offer ways to figure out how to doubt what you’re seeing,” Morey says.

There’s no doubt that the illusion of finding truth in statistical significance still appeals to researchers in many fields. Morey hopes that, perhaps within a few decades, the null ritual’s reign of errors will end.