In this week’s ‘Behind the Paper’ blog post Sylvie Martin-Eberhardt (they/them) discusses their new research article “Multiple signalling increases both prey response and diversity in a carnivorous pitcher plant“. Sylvie, a PhD candidate at Michigan State University’s Kellogg Biological Station, discusses the logistics of engineering artificial pitcher plants, the perils of conducting fieldwork in a peat bog, and the value of cultivating multiple mentoring relationships.

Carnivorous plants use many different lures to attract prey: red coloration, scent, UV reflection, and nectar secretions. Why invest in all these different attractants and risk hostile eavesdroppers like predators, herbivores, competitors, parasites, or robbers? While there’s been a lot of work on this question of ‘multiple signalling’ in animal behaviour, it has seldom been generalized to plant signalling, especially antagonistic (rather than mutualistic) signalling. We tested two hypotheses for multiple signalling in the purple pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea): 1) do these additional signals attract a greater diversity of prey and 2) do multiple signals ensure the attraction of a major prey item? To our surprise, we found support for both hypotheses: multiple signals attract a wider variety of prey as well as a greater abundance of one key prey item (a habitat-specialist ant). For the plant, adding additional signals substantially increases its total prey intake and diversity of prey it attracts. This increase could help the plant take advantage of seasonal flushes of different insects, or get a balanced diet of macro- and especially micro-nutrients. More broadly, we demonstrate multiple simultaneous benefits of multiple signalling, and show that the benefit of adding an additional signal to a display was about equal to its benefit in isolation; signals did not interact with each other to create a response greater than the sum of each signal alone.

To answer these questions, we used artificial plants, which allowed us to create a ‘plant’ with any combination of prey-attracting signals. We made them from Falcon tubes, typically used to store small amounts of liquid in lab. We added some water and a slippery substance called fluon to prevent insects from escaping, and to give them the shape of a real pitcher , added plastic ‘hoods’ made of corrugated yard sign. It was a fun engineering project to outfit them with realistic pitcher plant signals: artificial nectar pipetted on the rim, little disks of silicone soaked in scent compounds and suspended inside the tube but above the water, and paint that matched the pattern and color of the real plant, even in the UV, which insects can see but we humans cannot. I had two wonderful undergraduate students working with me during the summer I collected most of the data; one of them was an accomplished artist who did an amazing job painting the same venation pattern on 100 little tubes.

It was a huge undertaking to get all the pieces out to the field, assemble them on a little ‘mobile lab’ (shallow plastic bins) and place them in small groups (one per treatment) throughout the bog. Because we were creating artificial scents, everything had to be very carefully timed to get the right scent emission around 11 am, when the day had warmed up and insects were active, and ideally, we had everything set up and were out of the bog. The next day, we collected and disassembled all the models exactly 24 hours later, in the same order we set them up.

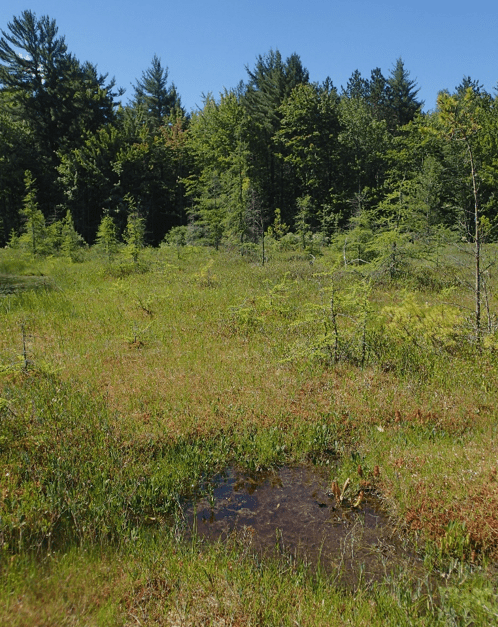

Peat bogs are wonderful habitats full of interesting species, but they are hard places to work. They are very fragile mats of peat moss and roots floating on the surface of a lake, and they can move under you with every step. There’s no sitting down, no kneeling, no setting your notebook down next to you. Everything is either in your pocket, tied to you, or in a plastic bin that can float, and every step is carefully chosen to minimize the impact on the bog. We called the fieldwork for this project ‘bog twister’, because once you plant your feet in one spot, you move them as little as possible while you place or collect models to avoid trampling vegetation or creating a hole in the peat mat.

Beyond all these logistical challenges, we also had major problems creating biologically realistic artificial scents. Artificial scents are complex and volatile, and moderate changes in their concentration can have big effects on animal behaviour. Since different compounds evaporate at different rates, we used a recent methods paper to calculate the concentration of scent compounds that would yield just the right blend hours later. Soon after I completed the fieldwork, I learned that the methods paper we had based our calculations on had issued a correction to their units, indicating our pitcher plant sent was a thousand times too strong. It takes real bravery to issue a correction, I am forever thankful that the authors took the time to make the correction public. Without their effort and integrity, I would not have figured out why my validation experiments didn’t match my expectations, nor would I have successfully created a biologically realistic scent blend, allowing me to conduct a follow-up experiment the next spring. This experiment ultimately revealed that, although the too-strong blend attracted insects, the corrected, realistic blend did not, showing for the first time that, at least for this species, the hypothesis that scents attract insect prey in this group of plants wasn’t supported. There were some huge ups and downs with trying to mimic a natural scent in the field, but we got some interesting results, and it was a good introduction to scent chemistry for me.

I am currently a PhD student at Michigan State University; I did the bulk of this work in my second summer in graduate school. I got involved in research as an undergraduate, and although much of my work was greenhouse- or lab-based, and I spent a lot of time scheming how to do more fieldwork. My undergraduate self would be really excited that my PhD involved carnivorous plants, canoes, and extensive fieldwork. As a researcher, I started out in love with carnivorous plants, but during my PhD, that has morphed into an obsession with plant coloration, and especially red leaves, stems, roots, extrafloral nectaries – red coloration in non-floral tissues raises the most interesting questions for me.

Outside of research, I love bicycling on the rural roads around Kellogg Biological Station where I live and work and sometimes manage to combine this with my love of foraging for fruit by bicycling out to pick berries. Michigan summers are this wonderful series of berry bonanzas, both farmed and wild, and every year my goal is to eat as many as possible.

Looking back on this project, the value of cultivating multiple mentoring relationships really stands out. I am fortunate to have two advisors (Marjorie Weber and Kadeem Gilbert, both authors on this paper) who gave their expert guidance on many aspects of this project. In addition, Dr. Shayla Salzman (University of Georgia) was a critical consultant on the artificial scent part of this paper, and she has been an incredible mentor to me during and after this project. Having many mentors to call on for different expertise and aspects of a PhD is incredibly valuable, and I wish it were more encouraged in our US academic system to cultivate robust mentoring relationships in addition to the advisor-student relationship. I highly recommend seeking advice and feedback from other scientists in addition to one’s advisor(s).