Dr. Lyndsey McMillon-Brown was hoping to see anything but mustard yellow. When the NASA research electrical engineer clicked open the photo of a small solar cell material sample – a swatch of film no bigger than a sticky note – she let out a cheer.

The film was still dark black after spending 10 months on the International Space Station, proving her team’s innovative solar cell material is suitable for possible use on future space missions.

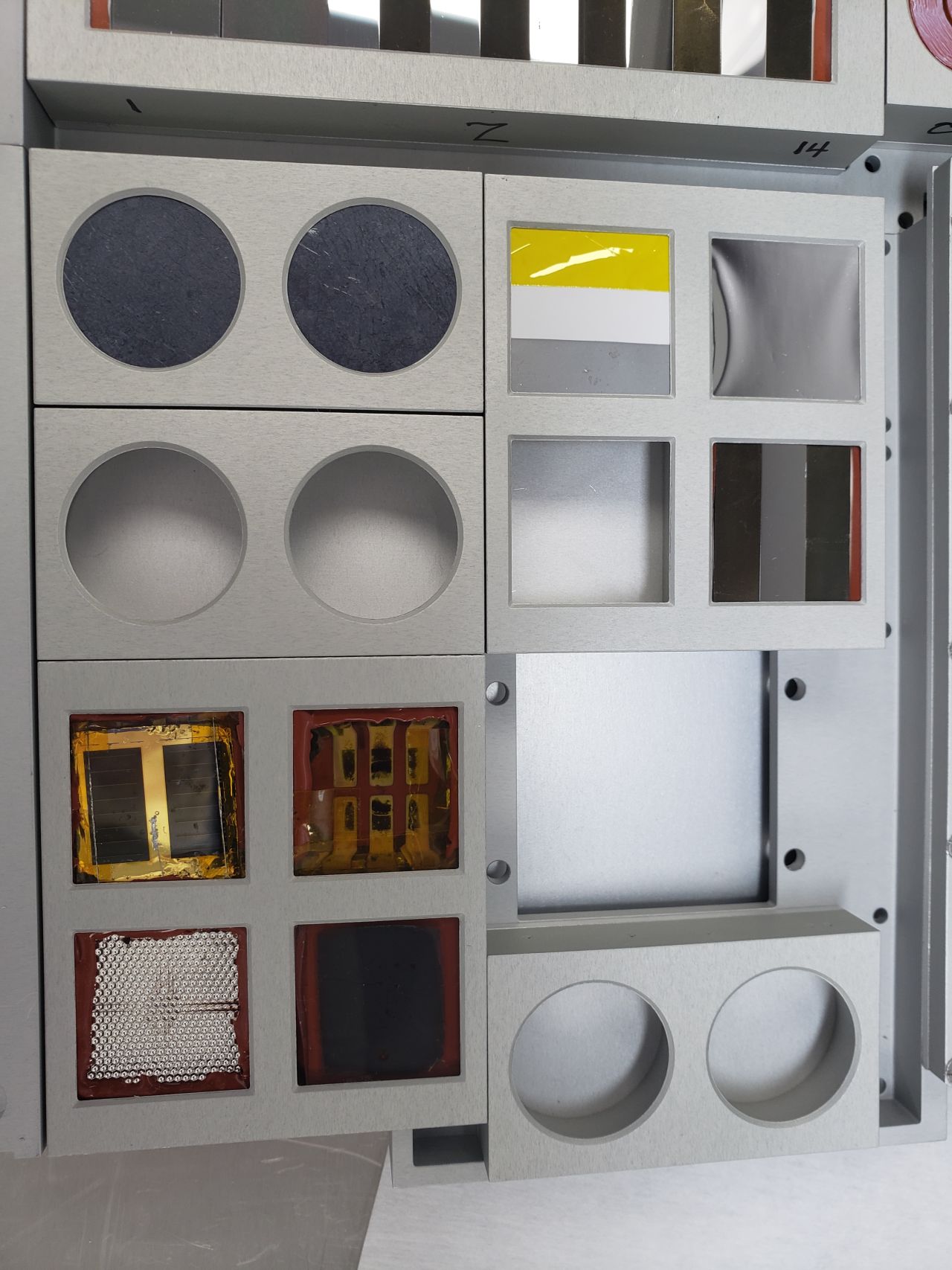

An image of the solar cell material – perovskite – samples inside the MISSE Platform installed on the exterior of the International Space Station. Image credit: NASA

McMillon-Brown’s space station-tested sample was part of the first spaceflight demonstration led by NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland to explore if this new material – called perovskite – is durable and can survive the harsh environment of space. The dark color she saw was an early indication the demonstration had been successful.

Dark black meant the perovskite film was in its most efficient form for absorbing light, while yellow would have meant the crystalline material had degraded into lead iodide, which isn’t useful for solar cells.

NASA Glenn’s perovskite sample can be seen as it was integrated into the MISSE platform at Aegis in Houston, Texas prior to launch to the International Space Station. Image credits: NASA

“We didn’t know when we sent it exactly what to expect,” McMillon-Brown said. “It was kind of like opening a door and not knowing what is going to be on the other side.”

If humanity is to establish a long-term presence on the Moon and Mars, astronauts will need reliable power sources to sustain their habitats and science instruments.

NASA researchers think perovskite could be used in solar cells that are thinner, cheaper, lighter, and more flexible than those currently made of silicon or group III and V elements on the periodic table.

Although perovskites had been put through the experimental paces on Earth, flying in space meant the material could be simultaneously pummeled by vacuum, extreme temperatures, radiation, and light stressors.

“There is no ground analog, no machine that will do all of those crazy things to it at the same time quite like the International Space Station,” McMillon-Brown said.

The 1-inch by 1-inch flight sample was created in a lab in early 2019. Once the thin film met strict safety requirements, it rocketed off to the space station in March 2020 as a part of the Materials International Space Station Experiment (MISSE).

Astronauts performed a spacewalk to open the suitcase-like MISSE platform and attach it to the outside of the space station, exposing the perovskite and other experiments to the extreme conditions of space.

After hurtling around in orbit and plunging in and out of direct sunlight for nearly a year, the film returned to Earth in January 2021.

The sample was analyzed by partners at the University of California Merced, led by Professor Sayantani Ghosh, where scientists studied what happened to it and compared it to a control sample that stayed on the ground. Partners at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory also contributed to the post-flight analysis.

Researchers had two key takeaways. Temperature swings during orbit constantly shrank and expanded the sample, putting stress on it and changing how it interacted with light. But they discovered something surprising – when the space-traveling perovskite was bathed in light back on Earth, its built-up stress relaxed, and its sunlight-absorbing qualities were restored, unlike the control sample, which degraded when exposed to the same conditions.

NASA solar cell material sample – close up. Image credits: NASA

This is a valuable quality, McMillon-Brown says, because it means perovskite solar cells could be used in space during long-duration missions.

“We don’t know exactly what about the space environment gave our film this superpower,” she said.

The other takeaway was that temperatures in space influenced how perovskite’s crystals were arranged, changing how they absorbed light for the better.

“The fact that the one in space holds a favorable arrangement for longer and can work at much lower temperatures is also a strong benefit for this material,” McMillon-Brown said.

Up next, McMillon-Brown and her team are isolating what specific parts of the space environment transformed the perovskite. And soon, they’ll be combing through results from complete perovskite solar cell experiments that have flown on the space station in the time since the first sample was returned.

“A lot of people doubted that these materials could ever be strong enough to deal with the harsh environment of space,” McMillon-Brown said. “Not only do they survive, but in some ways, they thrived. I love thinking of the applications of our research and that we’re going to be able to meet the power needs of missions that are not feasible with current solar technologies.”

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration